From Emily Zarevich for JSTOR Daily: “Flamboyant, swashbuckling cross-dressing was nothing new in late nineteenth-century France. Paris’s unique and bohemian lesbian subculture allowed these women to thrive, though it was still illegal for French women to wear pants in public. Yet despite the dangers and the occasional assaults, Belle Époque aristocrat and performer Mathilde de Morny (1863–1944)—better known by her alias “Missy”—still committed to her daring butch look, cutting her hair short, donning tailored three-piece suits, and smoking as many cigars as she pleased. Missy built her artistic career on the publicity raked in from her mannish attire and character, her queer-coded tendencies, and her adoption of masculine nicknames. Besides “Missy,” she answered to “Oncle (Uncle) Max” and “Monsieur de Marquis.” Like the French writer George Sand, who bunked down with composer Frédéric Chopin and poet Alfred de Musset, Missy selected her lovers from among France’s creative elite.”

At Japan’s dementia cafes, forgotten orders are all part of the service

From Michele Ye Hee Lee for the Washington Post: “The 85-year-old server was eager to kick off his shift, welcoming customers into the restaurant with a hearty greeting: “Irasshaimase!” or “Welcome!” But when it came time to take their orders, things got a little complicated. He walked up to a table but forgot his clipboard of order forms. He gingerly delivered a piece of cake to the wrong table. One customer waited 16 minutes for a cup of water after being seated. But no one complained or made a fuss about it. Each time, patrons embraced his mix-ups and chuckled along with him. That’s the way it goes at the Orange Day Sengawa, also known as the Cafe of Mistaken Orders. This 12-seat cafe in a suburb in Tokyo, hires elderly people with dementia to work as servers. A former owner has a parent with dementia, and the new owner agreed to let them rent out the space each month as a dementia cafe. The organizers now work with the local government to get connected to dementia patients in the area.”

The World Brain: H.G. Wells’ prophetic 1930s vision for the internet

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45737616/3177001.0.0.jpg?w=525&ssl=1)

From Maria Popova at The Marginalian: “On August 20, 1937 H.G. Wells addressed the archivists, librarians, and bibliographers gathered at the World Congress on Universal Documentation in Paris, where the encyclopedia had been invented two centuries earlier. Wells made a daring proposition: Saving humanity from itself calls for the creation of a new system for “universal organisation and clarification of knowledge and ideas.” He called it a World Brain — a “permanent central Encyclopaedic organisation with a local habitat and a world-wide range,” democratizing that supreme antidote to propaganda and manipulation: knowledge. The World Brain would be readily available to every human being, no matter their income level or the political rule of their society “a sort of cerebrum for humanity, a cerebral cortex which will constitute a memory and a perception of current reality for the entire human race.”

Editor’s note: If you like this newsletter, I’d be honoured if you would help me by contributing whatever you can via my Patreon. Thanks!

The lost history of Sextus Aurelius Victor

From Justin Stover for Antigone Journal: “Around 380 AD, the famous and irascible translator, Christian theologian, and general polymath, St Jerome, sat down to write a letter. Unsurprisingly, it was about books. One of them was the History of Sextus Aurelius Victor. Born in rural poverty in North Africa to an unlettered father, Victor rocketed to fame in 361, when he was summoned to Naissus by the Emperor Julian. Julian was so impressed by the North-African historian that he commissioned a bronze statue to be set up in his honour and made him governor of the province of Pannonia Secunda. It is no exaggeration to suggest that Victor was the Latin historian of the later 4th century. Most readers might reasonably wonder, therefore, why they have never heard of him.”

Instructions on how to use the new device known as a telephone, from 1896

From Futility Closet: “To Listen: Place the telephone fairly against the ear, with an upward motion, so that the lower extremity or lobe of the ear is gathered in, into the cavity of the telephone; in this position it will be found to fit snugly and comfortably — the lobe of the ear acting as a cushion and at the same time closing out all ulterior sounds, thus enabling the voice to be heard with clearness and precision.” AT&T promoted a Telephone Pledge that read, “I believe in the Golden Rule and will try to be Courteous and Considerate over the Telephone as if Face to Face.” The winner of a 1910 Bell essay contest wrote, “Would you rush into an office or up to the door of a residence and blurt out ‘Hello! Hello! Who am I talking to?’ No, one should open conversations with phrases such as ‘Mr. Wood, of Curtis and Sons, wishes to talk with Mr. White. In America Calling (1992), Claude S. Fischer notes, “Companies cut off service to abusers and obtained legislation that fined or even jailed profane customers.”

The perils of Pearl and Olga: A true crime story from 1950s Manhattan

From St. Clair McKelway in the New Yorker, in 1953: “On the morning of December 31, 1946, two young women got on a subway train separately at the Fifty-fifth Street station in Brooklyn, and sat down across from each other in a car as the train moved off. They had never met, had never spoken, but their lives had been drawn together and the entwinement was a sinister one. They were both working girls and more than ordinarily attractive. One of them was tall, with pale, clear skin and large, dark eyes and shining black hair; she was twenty-eight years old. She had noticed that the other girl was carrying a gift-wrapped package about the size of a large shoe box. It had an aperture at one end, from which protruded what looked like the lens of a camera. The other girl was barely nineteen and was small and blond. Her name was Pearl Lusk.”

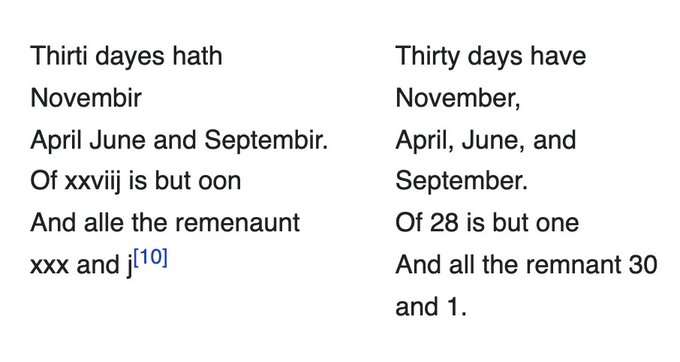

The “Thirty Days Hath November” rhyme dates back to the 1400s

From Depths of Wikipedia on Twitter

Bridgy Response

Bridgy Response