From Ian Sample for The Guardian: “When the blast from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius reached Herculaneum in AD79, it burned hundreds of ancient scrolls to a crisp in the library of a luxury villa and buried the Roman town in ash and pumice. The disaster appeared to have destroyed the scrolls for good, but nearly 2,000 years later researchers have extracted the first word from one of the texts, using artificial intelligence to peer deep inside the delicate, charred remains. The discovery was announced on Thursday by Prof Brent Seales, a computer scientist at the University of Kentucky, and others who launched the Vesuvius challenge in March to accelerate the reading of the texts. Seales and his team released thousands of 3D X-ray images of two rolled-up scrolls and three papyrus fragments, along with a program they had trained to read letters in the scrolls based on subtle changes in the structure of the papyrus.”

Flipped coins found not to be as fair as thought

From Bob Yirka at Phys.org: “A large team of researchers affiliated with multiple institutions across Europe, has found evidence backing up work by Persi Diaconis in 2007 in which he suggested tossed coins are more likely to land on the same side they started on, rather than on the reverse. The team conducted experiments designed to test the randomness of coin flipping and posted their results on the arXiv preprint server. For many years, the coin toss (or flip) has represented a fair way to choose between two options—which side of a team goes first, for example, who wins a tied election, or gets to eat the last brownie. Over the years, many people have tested the randomness of coin tossing and most have found it to be as fair as expected—provided a fair coin is used.”

Note: This is a version of my personal newsletter, which I send out via Ghost, the open-source publishing platform. You can see other issues and sign up here.

When tracking eagles via text message starts to get expensive

From Dan Lewis at Now I Know: “In 2015, a team of Russian ornithologists began a study to learn about the migration paths of eagles, an endangered species that breed in Russia, Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan. To better understand the birds, the researchers outfitted 13 eagles with trackers; each tracker sent a message with the eagle’s location four times a day. In the summer of 2019, one of the birds, named Min, flew to Kazakhstan, as the birds typically did. But for months, Min stopped sending tracking data back — researchers weren’t sure if Min had died or if he had simply gone to a region without good cell coverage. Thankfully, it turned out to be the latter; in October 2019, he reappeared on their trackers. And all of the text messages he should have been sending during his flight? They were all still queued up to send, and subject to international roaming fees.”

Editor’s note: If you like this newsletter, I’d be honoured if you would help me by contributing whatever you can via my Patreon. Thanks!

Some people have the ability to see hundreds of millions of colours

From Mike Sowden at Everything is Amazing: “Our ability to see colour is down to our chromosomes, the threadlike structures woven with DNA & located in the nucleus of our cells. Specifically, it’s about the type called an X-chromosome. Almost all women have two X-chromosomes. Almost all men have an X and a Y. The genetic code for our red and green photoreceptors is located on the X-chromosome. This is why far more men are colour-blind than women – a man only needs to have one receptor gene go haywire on his single X-chromosome, while a woman would need the same malfunction on both at the same time. If the end result is two entirely new cone mutations, one on each X-chromosome, these individuals might, in theory, see colours derived from four different pigments – making them tetrachromats. In doing so, they can go from seeing the world most of us see to one that has a hundred times more colours.”

The deadliest fire in US history killed more than a thousand people in Wisconsin and Michigan

From Matthew Wills for JSTOR Daily: “On the night of October 8, 1871, more than three square miles of the heart of Chicago burnt down. Around 300 inhabitants lost their lives. The Great Chicago Fire is certainly famous, but it wasn’t the only big fire that night. Two hundred miles north, a firestorm swept through 2,400 square miles of Wisconsin and Michigan and claimed more than 1,100 lives. The Peshtigo Fire, named after the Wisconsin town incinerated in the blaze, remains the nation’s deadliest wildfire. Because it was a major metropolis, the Great Chicago Fire got all the attention that night and many afterwards. The Peshtigo Fire, meanwhile swept through a sparsely inhabited frontier. News of the fire didn’t even reach the state capital in Madison until October 10.”

Fake history: Castle staircases were not built clockwise to make it hard for invaders

From Fake History Hunter: “This story has been making the rounds on the internet, but there’s no evidence for it whatsoever. The idea is that it’s easier for a right-handed soldier or knight to fight in a spiral staircase that is built going clockwise, as they had space to swing their weapon from above while the attacker coming from below would find this more difficult. Like many myths that stick, the story at first makes sense. But if you start looking for evidence, you soon realise there isn’t any. For starters, there is no primary evidence that the people who lived in these castles built staircases that way for that reason. During the Middle Ages, nobody wrote down that you should build staircases like this and why. If it had been common knowledge among castle builders, then why are there still quite a lot of castles with counter-clockwise staircases?”

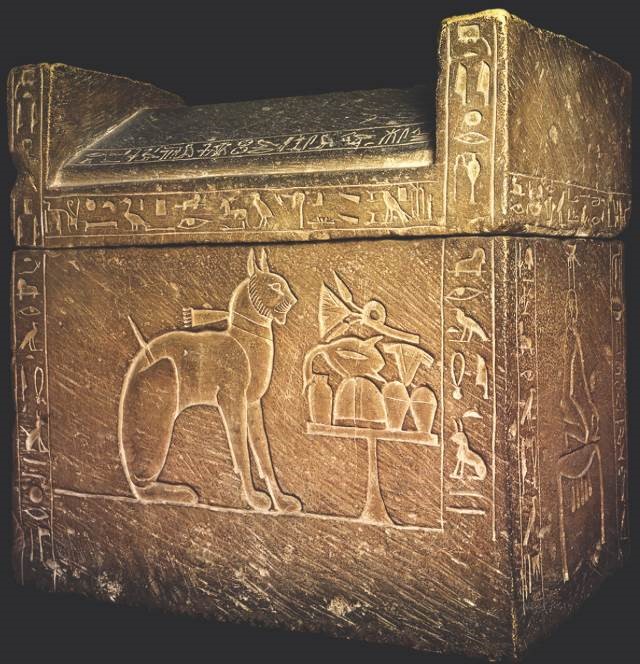

Egyptian prince Thutmose was entombed with his cat, Ta-Miu

From the Journal of Art in Society: “Egyptian prince Thutmose was entombed with his companion cat Ta-Miu (aka “little mewer”). Here’s the cat’s sarcophagus ~ an inscription says “I myself am placed among the imperishable ones that are in the Sky / For I am Ta-Miu, the Triumphant” (1,500 BC)”