From Adam Mastroianni at Experimental History: “There’s something very weird about the timeline of scientific discoveries. For the first few thousand years, it’s mostly math. The Greeks had the beginnings of trigonometry by ~120 BCE. Chinese mathematicians figured out the fourth digit of pi by the year 250. In India, Brahmagupta devised a way to “interpolate new values of the sine function” in 665. Meanwhile, we didn’t discover things that seem way more obvious until literally a thousand years later. It’s not until the 1620s, for instance, that English physician William Harvey figured out how blood circulates through animal bodies by, among other things, spitting on his finger and poking it into the heart of a dead pigeon. We didn’t really understand heredity until Gregor Mendel started gardening in the mid-1800s, and we didn’t really grasp the basics of learning until Ivan Pavlov started feeding his dogs in the early 1900s.”

The MacArthur Genius who discovered that COVID transmission was airborne

From Gabriel Spitzer for NPR: “To understand why the MacArthur Foundation singled out Linsey Marr for one of this year’s fellowships – the so-called “genius grants” – you have to go back to the first days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The early guidance from health experts emphasized washing hands and keeping six feet from others with no recommendation to wear masks or avoid gathering indoors. Linsey Marr, an aerosols expert and professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech, became convinced that advice was based on a flawed idea of how respiratory viruses spread. Her groundbreaking research and tireless advocacy showed that the virus is airborne as opposed to traveling in large droplets that fall with gravity. That work helped lead to a course correction in the public health guidelines and likely saved lives.”

Note: This is a version of my personal newsletter, which I send out via Ghost, the open-source publishing platform. You can see other issues and sign up here.

What can archaeology tell us about what the Druids were really like?

From Miranda Aldhouse-Green at Aeon magazine: “Gaius Verius Sedatus was a respectable citizen of the community of Chartres in the early 2nd century CE. He was a member of his local town council (a sort of mini-senate), where he and his colleagues presided over its laws and management, under the aegis of Roman law. Gaul had been conquered by Julius Caesar two centuries earlier and was now administered by trusted locals such as Sedatus, overseen by distant Roman officials. But Sedatus lived a double life. In the evening, he donned the mantle of a magician-priest and descended to his underground temple in the small cellar of his house. There he kept a group of four large incense-burners, placed symmetrically at the points of a square. He filled these vessels with aromatic, perhaps hallucinogenic herbs, and lit fires beneath them.”

Editor’s note: If you like this newsletter, I’d be honoured if you would help me by contributing whatever you can via my Patreon. Thanks!

A lab just 3D-printed a neural network made of living brain cells

From Celia Ford for Wired: “You can 3D print nearly anything: rockets, mouse ovaries, and for some reason, lamps made of orange peels. Now, scientists at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, have printed living neural networks composed of rat brain cells that seem to mature and communicate like real brains do. Researchers want to create mini-brains partly because they could someday offer a viable alternative to animal testing in drug trials and studies of basic brain function. At the start of 2023, the US Congress passed an annual spending bill pushing scientists to reduce their use of animals in federally funded research, following the signing of the US Food and Drug Administration’s Modernization Act 2.0, which allowed high-tech alternatives in drug safety trials. Rather than testing new drugs on thousands of animals, pharmaceutical companies could apply them to 3D-printed mini-brains—in theory.”

A young cop with a mountain of debt and two girlfriends found what he thought was a way out

From Katherine Laidlaw at Toronto Life magazine: “Robert Konashewych was a young police officer with expensive tastes, two girlfriends and a mountain of debt. Sometimes, he picked up paid-duty gigs at concerts, sporting events or government offices. One of his side jobs was with the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee, a branch of the Ministry of the Attorney General that most people never hear about—until they need its help. The OPGT is known as the decision-maker of last resort. More formally, it oversees financial, legal and personal care for mentally incapable adults who don’t have family to help them. About half of the agency’s clients collect disability payments from the province. On the first of the month, its office on Bay Street turns into a storefront. Clients arrive to pick up their cheques, and police officers like Konashewych come by to supervise. Heinz Sommerfeld was deceased, with a large unclaimed estate.”

After almost 150 years Gaudi’s masterpiece La Sagrada Família is almost finished

From Madeleine Muzdakis for My Modern Met: “Above the skyline of Barcelona rise high spindly towers. The cathedral known as la Sagrada Família has many of the hallmarks of classic gothic architecture, which could lead some unsuspecting viewers to believe it is medieval in origin. However, this many-towered house of worship is actually a modern masterpiece still under construction 141 years after its 1882 groundbreaking. The building project has endured through funding difficulties, the Spanish Civil War, and the death of its genius architect Antoni Gaudí. This fall, several of the highest towers were completed, marking one more step in the massive project that has spanned across three centuries. Gaudí began la Sagrada Familia with the Nativity façade, a detailed sculptural creation which was intended to be a teaching tool for those who could not read the Bible. The architect died in 1926, but work on the yet unfinished church continued.”

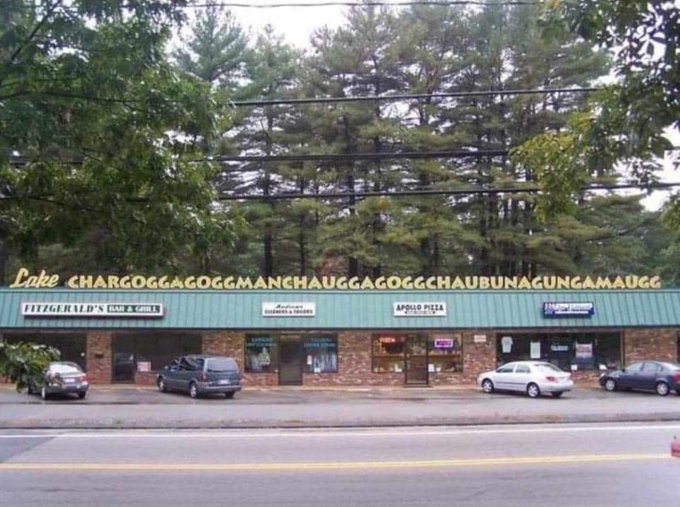

This lake in Massachusetts has the longest name of any geographical feature of the US

From Massimo on Twitter: “Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg in the town of Webster, Massachusetts, has the longest name of any geographic feature in all of the United States with 45 letters comprising 14 syllables”