Sometimes it feels like yesterday and sometimes a hundred years ago

Links that interest me and maybe you

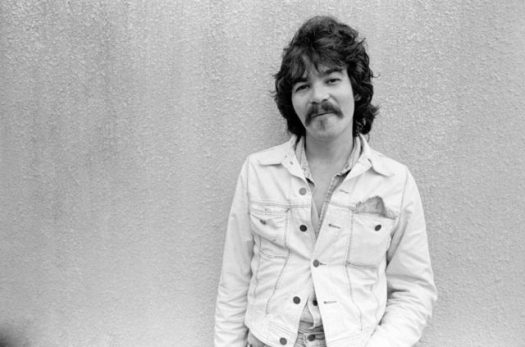

When I first started learning how to play the acoustic guitar, way back in about 1978 or so, one of the first artists whose songs I learned was John Prine (the other was Neil Young, and later on Leon Redbone, who passed away last year). One of the things I liked about John Prine was that he only ever used about four chords, and they were really easy to play — G, D, C, maybe an A minor now and then. But as I got to know him and his songs, it became increasingly clear that he was a genius — not a musical genius perhaps, but definitely a songwriting genius. A true poet, in the same vein as Dylan or Springsteen, but his songs are arguably a lot less cryptic than the former’s and a lot less mythical than the latter’s.

Prine songs are deceptively simple: They are about normal people named Donald or Lydia or Linda or Rudy, people with simple lives that consist of being in the army, working in factories, growing old, walking down the railway tracks in the winter, etc. But there is magic in the way John Prine writes about them — he lulls you into a false sense of security in some songs, with some light-hearted, feel-good banter, and then he hits you with a line that cuts like a knife. Something so artfully stated that it reveals an insight about human nature with only a few well-chosen words. Springsteen told Rolling Stone: “He was never anything but the loveliest guy in the world. He wrote music of towering compassion with an almost unheard-of precision and creativity when it came to observing the fine details of ordinary lives.”

“There’s a hole in Daddy’s arm where all the money goes. Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose” Sam Stone

In a remembrance that he sent to music writer Bob Lefsetz for his Lefsetz Letter, musician Tom Rush mentioned what he called “the sideways, sometimes upside-down takes on life that had us smiling and singing along. Ways of looking at things that were new to the world but were expressed so forcefully and engagingly that you could not turn away — there was no choice in the matter, you had to love him. No movie-star looks, no soaring tenor or dazzling guitar licks. He didn’t need them. He saw truths that had never before occurred to us, and offered them up in a brand-new, loving way that could not be denied.”

Continue reading “John Prine 1946-2020 — death of a legendary singer/songwriter/poet”Note: This is a post I wrote originally for the Columbia Journalism Review, where I am the chief digital writer

Both Google and Facebook have acted surprisingly quickly to remove disinformation related to the COVID-19 virus over the past few weeks, considering their somewhat mixed track record when it comes to removing hoaxes, conspiracy theories, and trolls related to political campaigns. But experts there is still a lot more that they and other digital platforms could be doing. CJR spoke this week with Karen Kornbluh and Ellen Goodman, co-authors of a new paper published by the German Marshall Fund entitled “Safeguarding Digital Democracy,” which includes a series of steps they say the major digital platforms need to take in order to deal with the problem. Kornbluh is a former US Ambassador to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and a senior fellow at the GMF and director of the Digital Innovation and Democracy Initiative, and Goodman is a professor at Rutgers Law School and co-founder and co-director of the Institute for Information Policy & Law.

In addition to Kornbluh and Goodman, CJR also held two roundtables with other experts using our Galley discussion platform, one of which included Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University; Dipayan Ghosh, co-director of the Digital Platforms & Democracy Project at Harvard’s Kennedy School; Mark MacCarthy, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Technology Law and Policy at Georgetown Law school, and Victor Pickard, an associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication. The second roundtable with Goodman and Kornbluh also included Marc Rotenberg of the Electronic Privacy and Information Center; Kate Klonick from St. John’s University law school; Enrique Armijo, a law professor at Elon University; Gus Hurwitz from the Nebraska College of Law; and Evelyn Douek, a doctoral student at Harvard Law School.

“The policy debate on disinformation has been hobbled by a false choice between allowing platforms or the government to censor. We propose instead empowering citizens through updating offline protections and rights (consumer protection, civil rights, privacy, campaign finance), supporting journalism and increasing accountability of platforms,” said Kornbluh. One of the things that would improve the overall information environment and counter-balance some of the worst of what the platforms do, she and Goodman suggest, is the creation of a PBS-style funding and distribution structure for digital journalism — an entity that they argue should be funded by a tax on the advertising revenues of Facebook and Google.

Continue reading “What Google and Facebook should do to fight disinformation”

Note: This is something I originally wrote for the daily newsletter at the Columbia Journalism Review, where I’m the chief digital writer

It’s the kind of problem many companies would love to have: Something happens that makes the world suddenly adopt your app or service by the millions, to the point where it becomes mission-critical for many, including journalists. Unfortunately for Zoom, the thing that happened is a global pandemic, and what it has done more than anything is expose some of the flaws and weaknesses in the service, which has become the de facto method of communication for everyone from politicians and teachers to doctors. Some of those flaws or weaknesses are mundane and even humorous, such as UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson inadvertently sharing the meeting ID number for a cabinet meeting he held via Zoom (which could allow someone to connect to the call without permission), or the manager who enabled filters for a conversation with friends, and then couldn’t turn them off and did an entire meeting as a potato.

Somewhat more serious than that (although still on the nuisance end of the spectrum), attendees on some Zoom calls have been interrupted by pornography and other misbehavior, thanks to a phenomenon that some are calling “Zoom-bombing” (from the term “photo-bombing,” which is when someone jumps into a picture without permission). Trolls appear to be dialing in to random Zoom calls and displaying porn videos or blasting other annoying forms of audio and video, since many Zoom calls can be joined with a simple nine-digit number. The company said in a statement that hosts can prevent this by requiring a password, or by making use of various features such as the Waiting Room, which hides a new visitor until the host allows them to enter. “We are deeply upset to hear about the incidents involving this kind of attack,” the company said.

Some flaws in the software, however, could be extremely serious, such as a Windows vulnerability that could allow hackers to steal someone’s credentials. All a user has to do, according to one report from a software security blog, is to click on a link in the Zoom chat window, and if a hacker has configured the link properly, it will connect to the user registry within Windows and provide the user’s login and password (although Windows sends this in encrypted form, a researcher was able to decrypt the user info in less than 30 seconds with a standard PC). This kind of vulnerability could be a significant problem for journalists or aid workers and other agencies who need to keep their conversations anonymous for various reasons. It’s not the first back-door style vulnerability Zoom has seen: Until late last year, the app secretly installed a hidden web server on Mac computers that could potentially be used by hackers to take control of a computer’s video camera (Zoom has removed this feature).

Continue reading “Zoom under pressure as the world relies on it to communicate”