Tearing Down the Myth of Paul Gauguin

Daisy Lafarge’s new novel makes it impossible to separate the art from the artist.

Reading Paul Gauguin’s fictionalized travelogue, Noa Noa, you’d be forgiven for thinking he’d stumbled upon an artist’s idyll when he arrived in Tahiti in 1891. “All the joys—animal and human—of a free life,” he wrote, “are mine.” Once a successful stockbroker in Paris, Gauguin told the French newspaper L’Echo de Paris before he left for Tahiti that he was rejecting the stifling “influence of civilization” to devote himself to art and pleasure. Despite his disappointment with how much French colonial rule had corrupted the island, Gauguin’s fascination with Polynesian culture and what he referred to as its “primitivism” characterizes much of his best-known work. His devotion to his artistic vision at all costs—his quest for creative paradise—has continued to intrigue us well into the 21st century. As Gauguin himself predicted, he has become more of a myth than a man.

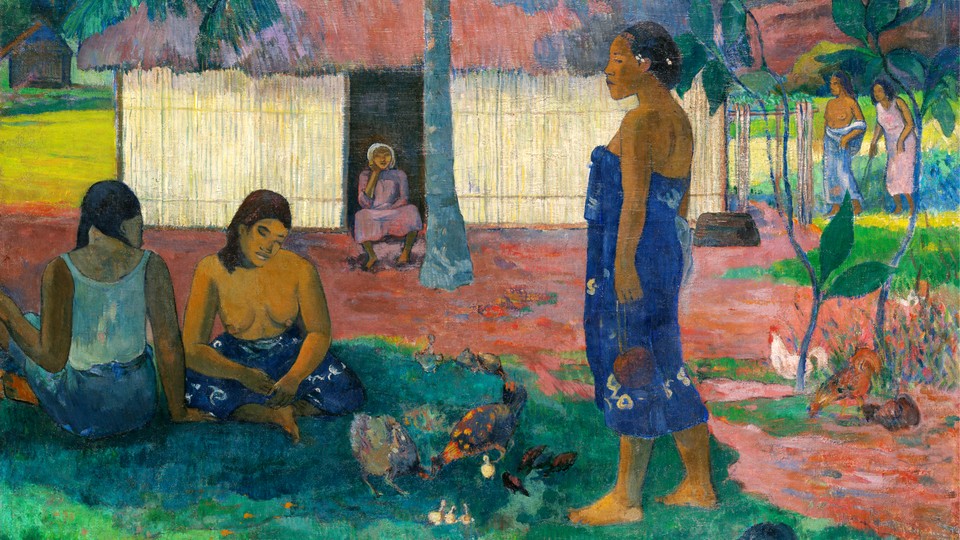

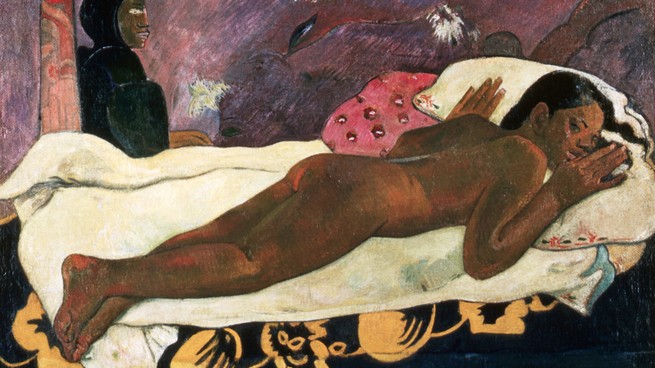

Less appealing, however, is his documented proclivity for the young girls who served as his lovers and frequent subjects of his work. In his 1892 painting Manaò tupapaú (Spirit of the Dead Watching), a nude girl lies on her front, staring up at the viewer, on display and seemingly terrified. Gauguin’s biographers commonly assert that her name was Teha’amana; she was reportedly 13 when Gauguin pursued her, eventually giving her syphilis and impregnating her. More than 100 years later, in 2017, Louis Vuitton used Delightful Land, featuring a nude girl—likely Teha’amana—as a design for a luxury-handbag collection. That same year, Gauguin’s drawings of Polynesian women and girls were animated and projected onto the facade of the Grand Palais, in Paris, beaming out to passersby.

Daisy Lafarge’s debut novel, Paul, takes a unique approach to an ongoing question: How, in the age of the #MeToo movement, should we interact with the work of men like Paul Gauguin? Superficially, Paul appears to follow in the vein of recent novels that address psychological and sexual violence––most notably Megan Nolan’s Acts of Desperation and Kate Elizabeth Russell’s My Dark Vanessa––by centering on a vulnerable young woman’s relationship with an abusive man, and extrapolating the nuances of that relationship as broader indications of modern misogyny. But Paul does something more complex: Larfarge uses the thoroughly contemporary story of a traumatized graduate on her European gap year to boldly reinterpret Gauguin’s life and legacy. By reconstructing one of the giants of the artistic canon as an irredeemable villain, the novel makes it impossible to separate the art from the artist. The titular character, Paul, an evocation of Gauguin, is so obviously reprehensible that we are forced to condemn him—and thus Gauguin himself, by extension. What, Paul asks us, is so fundamentally valuable about the artist’s work that we continue to view, sell, and celebrate it more than a century later?

Transposed to the 21st century, Lafarge’s Paul is the boorish, middle-aged owner of Noa Noa, a Pyrenean organic farm (named after Gauguin’s book). The narrator, Frances, a shy woman with a degree in medieval history who was fired from her job as a research assistant in Paris, finds the farm on a work-exchange website. She arrives at Noa Noa, which quickly reveals itself to be more of a commune than a place of work. Soon Paul is asking that she come to bed, and over time, his treatment of her worsens into psychological and sexual manipulation. The situation drives an already fragile Frances to the point of involuntary muteness, a silence that recalls Gauguin’s voiceless, painted subjects. Like his namesake, Paul has spent significant time in Tahiti, where he claims to have found true artistic liberty. Paul also used the people of Tahiti as muses—photographing where Gauguin painted—and sees the country as nothing more than the exotic backdrop for his journey of self-discovery. And the book implies that, like Gauguin, Paul had sexual relationships with young girls, which he excuses on the basis of a “cultural difference” in Tahiti that permitted him to engage in child exploitation without consequences.

Where Paul does diverge from reality is in its purposeful refusal to explain away his behavior on the basis of brilliance. Lafarge denies Paul the defense of artistic value that so often absolves toxic creative types. Her Paul is not a brilliant artist; he is pathetic, failing. But though his behavior might immediately repulse readers, Frances is so desperate for guidance and security that she takes much longer to come to terms with who he really is. That slow process of realization guides the novel and is often staged in scenes of observation, drawing a parallel with the act of viewing a work of art.

In one passage near the end of the book, Frances watches Paul stare lustfully at a group of preteen girls. Later, faced with inarguable proof of his predatory pedophilia, she shatters. “It is so hard to look,” she thinks to herself. “So hard to look away.” Within that question––to look, or to look away?—Paul asks us to consider what we’re really seeing in paintings like Spirit of the Dead Watching. Frances’s discomfort becomes our own, blurring fiction and fact until it is impossible to think of Gauguin without the ugly specter of Paul.

Within the novel, censuring both men might be an obvious reflex, but in the real world, it’s much more fraught. “The person, I can totally abhor and loathe, but the work is the work,” Vicente Todolí, a former director of Tate Modern, has said of Gauguin. Viewers might ask: What harm can it possibly do to look at a painting when the subject and artist are both long dead? But the decision to exhibit Gauguin’s art is a conscious choice—and museums, of late, have decided to lay bare the artist’s behavior. So is the decision to consume his work. Lafarge, through Frances’s struggle to truly see Paul as he is, positions the act of witnessing—so often characterized as passive—as an act of complicity. Her inaction in the face of Paul’s behavior appears almost like acceptance, allowing Paul to continue deluding himself that he is “a good man.” Faced with Gauguin’s work, you are asked to make a calculation: Is the pleasure of observing it worth the pain of its production?

As the novel comes to a close, Paul takes Frances on an impromptu road trip to visit a series of his friends, most of whom appear ambivalent about him. “If I were a woman,” one man remarks to her, “I’d keep my distance.” In another scene, Paul pressures Frances to perform oral sex on him in a child’s bed, which palpably unnerves her. Growing ever more suspicious of Paul, Frances finally confronts him about his time in Tahiti. Predictably, he begins to weep. “I am not a bad man,” he says, begging for understanding. But Frances refuses. Instead, as they’re driving back to Noa Noa, she jumps out of his car and buys a ticket to Paris.

It’s not entirely satisfying as a resolution––Paul receives no meaningful comeuppance. Wisely, though, Lafarge leaves the central question of the novel open. Should we look, or should we look away? In Frances’s escape, Lafarge seems to land on the latter option. But there is another possibility, I think.

Earlier this year, the Alte Nationalgalerie, in Berlin, exhibited a series of Gauguin’s paintings juxtaposed against the work of artists attempting to reckon with his legacy. In one room, Gauguin’s paintings and etchings were positioned opposite a work of live-action video art by Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer, titled Why Are You Angry?, which was created in response to Gauguin’s No te aha oe riri. Dressed in the same clothes and posed in the same positions as the subjects of that painting, the girls in the video stared at you when you passed by. You could see their bodies shifting, their breathing, their human twitches. The line between person and figure blurred; you were unable to consider the master brushwork of Gauguin’s paintings without being aware of the eyes of the girls upon your back. You turned around. Time passed. They were still looking at you, answering your gaze with their own.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.