There are two St Cyprians. One is a martyr of the early church – a third-century bishop of Carthage who was put to death in AD258 by a proconsul of the emperor Valerian after refusing to pay obeisance to the pagan gods. The other, now regarded by scholars as a mythological figure and expunged from the Vatican's martyrology, was Saint Cyprian of Antioch. According to legend, he was a pagan sorcerer who converted to Christianity but secretly carried on with his magical practices. He is regarded as the patron saint of necromancers.

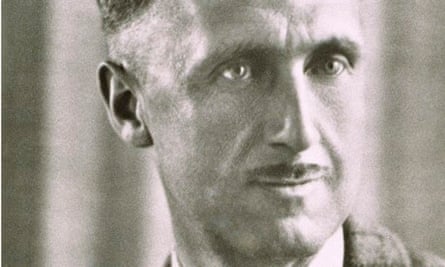

We can safely assume that it was the first Saint Cyprian – patron saint of North Africa, by the way – after whom the Eastbourne prep school the young Eric Blair attended was named. But from his account of his time there before and during the first world war – published many years later when he was better known as George Orwell – you'd be forgiven for imagining that it was the second saint.

The title of the long essay "Such, Such Were the Joys" – taken from Blake's rhapsodic Song of Innocence "On the Echoing Green" – is bitterly ironic. Orwell hated his time at prep school – or, at least, seemed to have decided that he hated it by the time he came to recall it in print. "Whoever writes about his childhood," he says, "must beware of exaggeration and self-pity. I do not claim that I was a martyr, or that St Cyprian's was a sort of Dotheboys Hall." Disclaimer issued, he does exactly that, in a performance of grotesque literary effectiveness.

To think of his schooldays is, he says, "to breathe in a whiff of something cold and evil-smelling – a sort of compound of sweaty stockings, dirty towels, faecal smells blowing along corridors, forks with old food between the prongs, neck-of-mutton stew, and the banging doors of the lavatories and the echoing chamber-pots in the dormitories".

St Cyprian's, Orwell writes, was "an expensive and snobbish school which was in process of becoming more snobbish, and, I imagine, more expensive". Its horrible headmaster Mr Wilkes and his still more horrible wife – they were nicknamed "Sambo" and "Flip" – presided over the school like cruel gods, fawning over the richer children and constantly reminding Orwell (a scholarship boy) of his second-class standing and the relative poverty of his parents.

It was a place of arbitrary and humiliating punishment, of extreme (and, he concedes, effective) physical cruelty: a dim boy is described as being flogged towards a scholarship exam "as one might do with a foundered horse", and of comical disgustingness. Under the overhanging rims of the porridge bowls, he writes, "were accumulations of sour porridge, which could be flaked off in long strips. The porridge itself, too, contained more lumps, hairs and unexplained black things than one would have thought possible, unless someone were putting them there on purpose."

The plunge-bath was "slimy", the towels "always-damp … with their cheesy smell" and on a rare winter visit to the local baths he sees in the "murky seawater" there is "floating a human turd". He writes of remembering a "pretty, mother's darling of a new boy" about whom the first thing he noticed was the "beautiful pearly whiteness of his teeth": "By the end of that term his teeth were an extraordinary shade of green."

More than physical disgust, Orwell is at pains to evoke a world of profound moral unease. "Such, Such" opens with a description of the seven-year-old narrator being beaten with a riding crop for wetting the bed, and then – because he was overheard telling another boy afterwards that "It didn't hurt" – being beaten again with such savagery that the riding crop broke: "The bone handle went flying across the room. 'Look what you've made me do!' the teacher "said furiously, holding up the broken crop".

The tears Orwell shed then, he writes, were not of anger or grief but of shame – "a conviction of sin and folly and weakness such as I do not remember to have felt before": "I can still recall my feeling as I saw the handle lying on the carpet – the feeling of having done an ill-bred clumsy thing, and ruined an expensive object. I had broken it: so Sambo told me, and so I believed. This acceptance of guilt lay unnoticed in my memory for 20 or 30 years."

Above all, then, Orwell zeroes in on the idea that here was a regime (the term seems apt) whose assumptions about the order of the universe are contradictory and unjust – yet at the same time unquestioningly internalised by its subjects. He hated Flip and Sambo and yet knew them to be his benefactors. He had no control over his bedwetting – though he prayed fervently for it to stop – yet was conscious of it as sin: "This was the great, abiding lesson of my boyhood: that I was in a world where it was not possible for me to be good."

"Such, Such" was never published in Orwell's lifetime. He himself said he thought it probably too libellous to print, and lawyers agreed: Secker & Warburg's libel report red-flagged more than 30 paragraphs of its 15,000-odd words. When Malcolm Muggeridge visited Secker & Warburg in early 1950, and talk turned to the possible inclusion of "Such, Such" in a collection of posthumous essays, publisher Roger Senhouse dismissed it as "full of self-pity". Muggeridge conceded the point, but likened it to a "dehydrated" version of David Copperfield. It only saw unexpurgated publication in the UK in 1968, after Mrs Wilkes was safely in her grave.

It is a very odd piece of writing. As a literary performance it takes its place alongside works such as Alec Waugh's The Loom of Youth and Cyril Connolly's Enemies of Promise – to which Orwell likely intended it as a sort of reply or companion piece. It is powerfully evocative, nakedly tendentious, and – as Senhouse noted – absolutely sodden with self-pity. What is perhaps oddest is that while you might expect it to show Orwell in analytical mode – a meditation on the way in which the private school system internalises expectations to do with class and hierarchy – you find none of that detachment. It hints at those themes but it is agonisingly personal, a howl of grievance when it is not a yelp of derisive laughter.

"There is this feeling at the bottom of it," says Orwell's biographer DJ Taylor, "and Orwell makes this point himself about Dickens writing about the blacking factory in David Copperfield, that deep at the heart of this is not so much a complaint that small boys are made to endure all this, but that I, George Orwell, or I, Charles Dickens, was made to endure all this."

The personal nature of the essay, then, should sound a note of caution. With as many Old Etonians in David Cameron's cabinet as were in Asquith's when Orwell went to St Cyprian's, and with Michael Gove bringing the squeak of chalk on blackboard back to the classroom, it is tempting to make claims for the contemporaneity of "Such, Such". Those parallels should be somewhat resisted.

In the first place, the sort of school that Orwell's essay describes – the single-sex boarding prep school staffed by sadists and reeking of gym socks, boiled cabbage and pederasty – is now distinctly on the wane. Few, even among the traditional upper classes, now dispatch their children to boarding school at the age of six or seven.

And there is a good deal of evidence to suggest that Orwell's account of his prep-school days was – how to put this? – a load of utter bollocks. Orwell's childhood friend Jacintha Buddicom said that the "I" of "Such, Such", "just was not Eric at all". She remembered him as a happy child, and such railing against St Cyprian's as she recalled was warmly humorous rather than bitter or aggrieved. Among several who left records of their time there, none strikes the same note. The golfer and sports writer Henry Longhurst said that Orwell's hated Mrs Wilkes was "the outstanding woman of my life", and when a dinner in her honour was given in 1951, 250 former pupils turned out.

"Unquestionably, Orwell intended it to be taken as literally true, which equally unquestionably, it is not," Taylor writes in his biography. He adds now: "It's a very literary performance. It's not reportage. It's very considered writing – looking back in time 25 years and very structurally coherent."

So what was going on? Did Orwell fabricate a miserable childhood? Or – in the trowelling on of improbably damning detail – was there a more general literary project in hand? Taylor points to the bizarre paranoia of one episode – in which the young Orwell, having sneaked out to buy chocolate from a sweet shop a mile or more from the school, emerged and took fright at a "small sharp-faced man who seemed to be staring very hard at my school cap".

"There could be no doubt who the man was," Orwell writes. "He was a spy placed there by Sambo! I turned away unconcernedly and then, as though my legs were doing it of their own accord, broke into a clumsy run. But when I got round the next corner I forced myself to walk again, for to run was a sign of guilt, and obviously there would be other spies posted here and there about the town."

A society in which one could be guilty without doing anything deliberate, in which surveillance was assumed to be total, and in which shame and fear and humiliation were profoundly internalised – it is, as Taylor suggests, more than plausible that "Such, Such" evinces a cross-contamination with Orwell's most famous novel.

"It is a fascinating piece," says Taylor, "because of the connections between it and Nineteen Eighty-Four. If you go back and read the descriptions of O'Brien, he is described as being first like a priest and then like a schoolmaster. It's almost like Winston Smith is the boy he is trying to reform. And I'm interested by all the totalitarian language in "Such, Such". Which piece came first – you can argue either way. In some ways the chronology isn't even important."

He adds: "The other point I'd make about it is how very alone the writer is – this tremendous sense of isolation. This is what Orwell does with his novels: he creates this almost entirely alone and friendless character at the mercy of vast and unappeasable forces that he or she has no way of comprehending or dealing with – and then the walls close in. That's the plot of all the five novels – I'm not counting Animal Farm – reaching its climax in Nineteen Eighty-Four. And exactly the same trick is played here."

"Such, Such" may be a distorting mirror, but it is a mirror nonetheless. Many of us will still recognise aspects of it – whether in the structures and assumptions Orwell describes, or simply in the childhood sense of being powerless in an alien institution. And, certainly, it is almost a truism that the sort of school, of which Orwell's St Cyprian's was an example – and the public schools which they fed – were and are instruments of social indoctrination. Here are little microcosms of the sort of authoritarian and hierarchical society that their products were expected to go on and govern. The cliche that the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton nods at this.

I didn't attend a boarding prep school, but I did go to Eton. I am younger than David Cameron and wasn't in his house (or "hice", as we Etonians like to pronounce it) so have no memories of our future leader. I do remember Damian Lewis as Wackford Squeers in a school production of Nicholas Nickleby, though – with Smike affectingly played by Rory Stewart, now MP for Penrith and the Border. The Eton I attended didn't ostensibly resemble Orwell's St Cyprian's, however, any more than it resembled Dickens's Dotheboys Hall.

That said, its forms and hierarchies were easily internalised. I attribute to my education not only an uncountable number of advantages and privileges, but some of the characteristics I find least attractive in myself. I have a craven teacher-pleasing tendency: a deference to authority and a desire to excel within parameters established by others rather than to challenge those parameters. I am a more conventional – sometimes timid – thinker than I would like.

One aspect of that school's setup – the prefect system – still seems to me a stroke of ideological genius: an object lesson in co-option. There, as in St Cyprian's and any comparable institution, "virtue consisted in winning": the strong and beautiful attracted hero-worship. So the apex prefect body, "Pop", is self-elective: the most popular boys – ie those most in a position to lead others astray – are also the most thoroughly bought and sold.

Their special privilege is to peacock about in coloured waistcoats – and for this, they will dutifully and without pay perform tedious prison-trusty duties such as spending hours in the rain on Windsor bridge preventing younger boys sneaking to the pub. What is cleverest is that they wear the price at which they've been bought – shiny buttons and a swatch of brightly coloured cloth – on their chests.

We can certainly see about us those – need we mention names? – to whom politics seems to be the continuation of private school by other means. For those for ever striving to regain the intoxication of having been a gilded god at 18, a cabinet post shines as the equivalent of election to Pop, and the prime ministerial job as the ultimate combination of head boy and victor ludorum.

At the same time there is a strong tradition of public schools acting on certain temperaments to produce absolutely the opposite: rebels whose anti-establishment zeal seems to have been fired by exposure to the rituals of that establishment at an early age. From Shelley (Eton) to Paul Foot (Shrewsbury), Tam Dalyell (Eton) to Tony Benn (Westminster), many prominent figures on the left have been public schoolboys.

"A school could be conducive to that, if you have a certain kind of mind, because it is a sort of oppressive dictatorship in miniature," says Karl Marx's biographer and Private Eye stalwart Francis Wheen. "Some of us found it so oppressive that we rebelled against it. I hated Harrow so much that I ran away when I was 16 and left a note for my parents saying: 'I've gone to join the Alternative Society' and scampered off to London and lived in a squat. It's fair to say in my case that my politics was formed in reaction to Harrow."

Talking about the current schisms in the Socialist Workers party, Wheen points out that the party's leader Alex Callinicos, grandson of the 2nd Lord Acton, was educated at a top private school and another senior leader, Charlie Kimber, is the Old Etonian son of a baronet. Also prominent in the brouhaha has been Dave Renton, an Old Etonian barrister related to a former Tory chief whip: "It sometimes reads like a conversation between Old Rugbeians and Old Etonians about the main British Trotskyist party. It's quite bizarre."

There is a popular school of thought, indeed, that holds that the treachery of the Cambridge spy ring was a reaction against their public school educations – an idea explored psychologically in (Old Wykehamist) Julian Mitchell's fine 1981 play Another Country. Lindsay Anderson's film If …, meanwhile, dramatised the idea of the public school rebel as a sort of violent dream.

Yet for all "Such, Such" might suggest this conclusion, Orwell himself – who had no complaint about his time at Eton – can't, on its evidence, be planted straightforwardly in the tradition of the public-school lefty. "No, no," says Taylor. "He's always much too idiosyncratic for that kind of thing. The thing about Orwell, which has become almost a cliche, is that he was a conservative in everything except for politics … It's very easy with Orwell to make it all teleological and work back – but in some ways he was very conventional. I don't think he was at all radicalised until the 1930s."

"Such, Such Were the Joys", then, remains a riddling and fascinating document. Rather than describing the formative experience for Orwell's vision of totalitarianism it may, instead, have been a description itself formed by that vision. To repurpose Eliot's line: "We had the experience but missed the meaning, / And approach to the meaning restores the experience." It is a black magic of which the mythical St Cyprian might have approved.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion