In 1991 an academic debate spilled out of ivory towers and into the popular imagination. That year, Serge Renaud, a celebrated and charismatic alcohol researcher at the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research—who also hailed from a winemaking family in Bordeaux—made a fateful appearance on 60 Minutes. Asked why the French had lower rates of cardiovascular disease than Americans did, even though people in both countries consumed high-fat diets, Renaud replied, without missing a beat, “The consumption of alcohol.” Renaud suspected that the so-called French paradox could be explained by the red wine at French dinner tables.

The French paradox quickly found a receptive audience. The day after the episode aired, according to an account in the food magazine the Valley Table, all U.S. airlines ran out of red wine. For the next month, red wine sales in the U.S. spiked by 44 percent. When the show was re-aired in 1992, sales spiked again, by 49 percent, and stayed elevated for years. Wine companies quickly adorned their bottles with neck tags extolling the product’s health benefits, which were backed up by the research that Renaud had been relying on when he made his off-the-cuff claim, and the dozens of studies that followed.

By 1995, the U.S. dietary guidelines had removed language that alcohol had “no net benefit.” Marion Nestle, professor emerita of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, was involved in drafting those guidelines. “The evidence in the mid-’90s seemed incontrovertible, whether you liked it or not. And boy, none of the people who were concerned about the effects of alcohol on society liked that research. But they couldn’t find anything wrong with it at the time. And so, there it was; it had to be dealt with. And it got into the dietary guidelines.”

The press ran with it. A New York Times front-page headline announced, “In an About-Face, U.S. Says Alcohol Has Health Benefits.” The assistant secretary of health said at the time, “In my personal view, wine with meals in moderation is beneficial. There was a significant bias in the past against drinking. To move from antialcohol to health benefits is a big change.”

Physicians were also changing their tunes. One influential alcohol researcher, R. Curtis Ellison—who made a cameo on that infamous 60 Minutes episode about the French paradox—wrote in Wine Spectator in 1998, “You should consume alcohol on a regular basis, perhaps daily. Some might even say that it is dangerous to go more than 24 hours without a drink.”

The results live in all of our heads: There’s nothing wrong with a glass of wine with dinner every night, right? After all, years of studies have suggested that small amounts of alcohol can favorably tweak cholesterol levels, keeping arteries clear of gunk and reducing coronary heart disease. Moderate alcohol use has been endorsed by many doctors and public health officials for years. We’ve all seen the Times headlines.

Now, 25 years later, you’re likely feeling a fair bit of whiplash. According to new guidelines released in recent months by the World Health Organization, the World Heart Federation, and the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction, the safest level of drinking is—brace yourself—not a single drop.

“Mainstream scientific opinion has flipped,” said Tim Stockwell, a professor at the University of Victoria who was on the expert panel that rewrote Canada’s guidance on alcohol and health. Last month, Stockwell and others published a new major study rounding up nearly 40 years of research in some 5 million patients, concluding that previous research was so conceptually flawed that alcohol’s supposed health benefits were mostly a statistical mirage. Much different headlines followed.

If you’re anything like me, you are greeting this most unfun of news with mild dismay but also great confusion. Why was it common knowledge yesterday that alcohol in moderation is good for you, but it’s common knowledge today that no amount of alcohol is OK? A closer look at how alcohol’s so-called cardioprotective effect gripped science and the culture reveals what led to the biggest flip-flop in health and lifestyle advice in recent memory. One entity that was never far away: the alcohol industry.

In 1974, a cardiologist at Kaiser Permanente in California published a provocative finding. Arthur Klatsky reported that among the 464 patients he and his colleagues were studying, heart attacks were highest among those who abstained from drinking alcohol. The paper was novel in that unlike previous studies, it controlled for several risk factors, including smoking—which is highly correlated with drinking, and can muddle epidemiological conclusions. It suggested that some alcohol was better for heart health than none at all. Scientists had been arguing over alcohol’s potential heart benefits for decades, and this finding supercharged the debate in the modern era of evidence-based medicine.

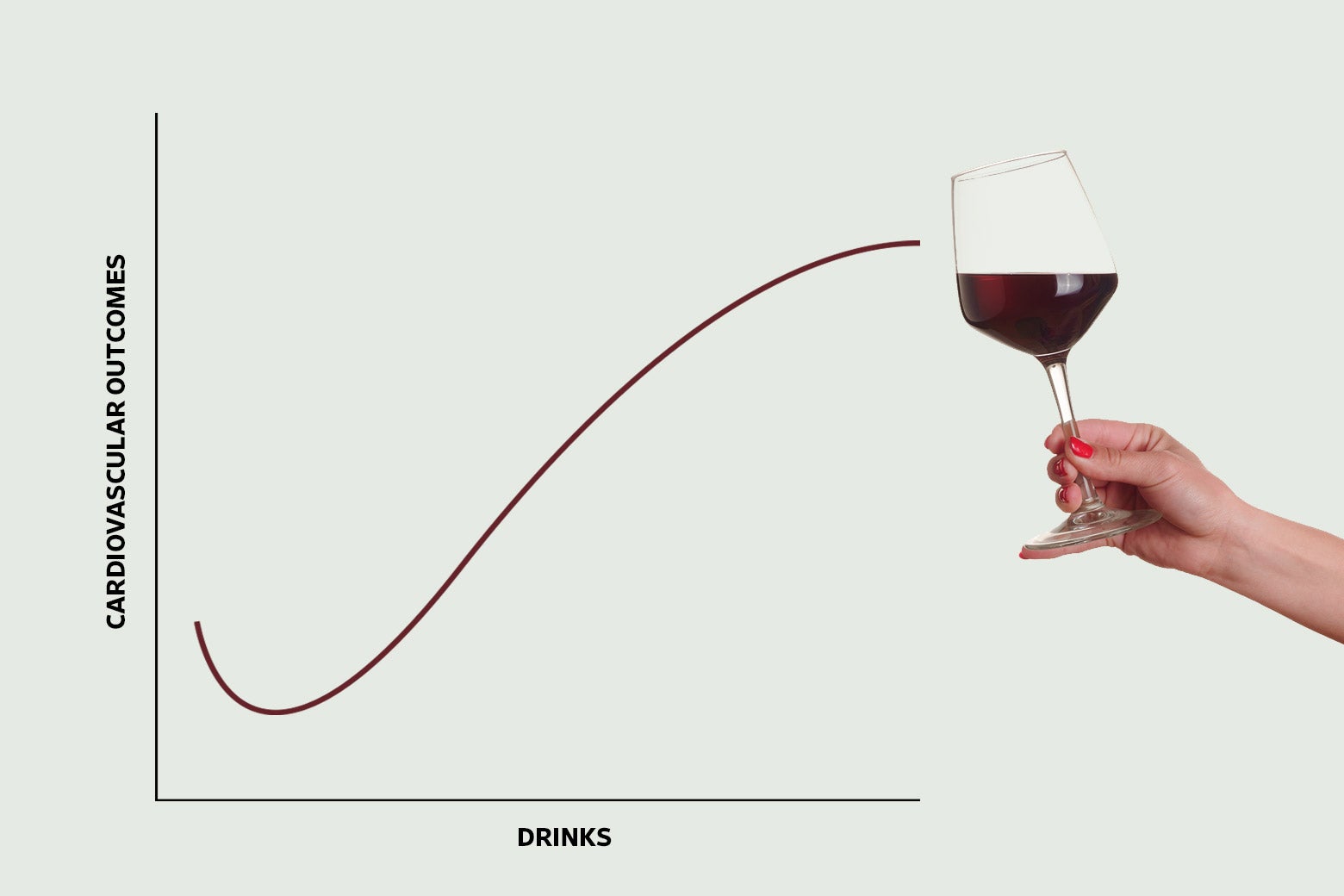

More good news for drinkers followed. In 1977 and 1980, researchers published findings from a study of nearly 8,000 men of Japanese descent living in Oahu, Hawaii, that investigated whether adopting a more Westernized lifestyle increased the low rates of coronary heart disease among Japanese people. The moderate drinkers fared better than the rest of the group. Then, in 1986, a major multigenerational study reported that moderate-drinking men in Framingham, Massachusetts, were 40 percent less likely to die of coronary heart disease. Both the Honolulu Heart Study and the Framingham Heart Study aligned with Klatsky’s findings. The research wasn’t exactly saying that alcohol was categorically healthy. The association is now called the “J-shaped curve,” because when cardiovascular outcomes are graphically plotted against number of drinks, the resulting curve resembles the letter J: Abstainers have a slightly elevated risk of heart disease, moderate drinkers have the lowest risk, and then the risk returns with a vengeance the more you drink.

Since these seminal studies, the J-shaped curve has been documented in dozens of observational studies totaling more than a million patients. On balance, they suggest that about one drink per day correlates with 14 to 25 percent less cardiovascular disease or death compared with abstaining. Several studies looking at “all-cause mortality” found that moderate drinkers were 14 to 20 percent less likely to die of anything than abstainers or heavy drinkers were. And while the initial excitement was about wine, some of the research focused on beer, with many papers not distinguishing between types of drinks. In theory, any type of alcohol should have the same cardioprotective effect.

Even though these observational studies can’t establish causation, the J-shaped curve is biologically plausible. As early as 1973, scientists discovered that alcohol raises levels of good cholesterol, and subsequent research showed that it decreases molecules that lead to blood clots. In 1994 researchers at Stanford University and the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Medical Center found that alcohol may even increase insulin sensitivity, which could account for an observed reduction in the risk of diabetes, which is itself a major risk factor for heart attacks.

An idea emerged in the literature that consistent, low levels of alcohol were acting like a vascular solvent, keeping arteries unclogged and preventing health problems down the road. Given this body of epidemiological and biomedical research, it was a reasonable scientific position to take that light drinking was good for some aspects of your health—though actually going so far as to recommend it created a dilemma for public health agencies, due to other known downsides.

Alcohol’s potential health benefits so distressed health authorities that, in a stunning bit of bureaucratic overreach, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute suppressed the results of the Framingham Heart Study for a full 14 years. “An article which openly invites the encouragement of undertaking drinking with the implication of prevention of coronary heart disease would be scientifically misleading and socially undesirable in view of the major health problem of alcoholism that already exists in the country,” wrote an associate director of the institute.

Then came 1991, Renaud’s 60 Minutes appearance, and a French paradox that the public couldn’t resist.

Ellison, the alcohol researcher who suggested it was “dangerous” not to drink for a day, went on to essentially recommend that physicians prescribe alcohol to their nondrinking patients. A cottage industry of research popped up to explore whether antioxidant compounds such as resveratrol could account for red wine’s salubrious properties. For a few carefree years, it seemed as if we could tuck into as much foie gras as we wanted so long as we washed it down with a glass of Beaujolais.

At least one researcher had doubts all along. In 1988, before the media circus began and the guidelines flipped, Gerald Shaper, an epidemiologist in London, put forth what is called the “sick-quitter hypothesis.” According to Shaper, it was possible that abstainers like those in Klatsky’s study and the Honolulu Heart Study had quit drinking because they had already developed a health problem. If abstainers were sicker, then moderate drinkers would look healthier.

To put his idea to the test, he analyzed the data from a major study, the British Regional Heart Study, but added a twist. He compared abstainers and moderate drinkers, just as in the original study—then separated them by preexisting cardiovascular disease. That way, he could compare groups of men with similar cardiovascular health profiles. The J-shaped curve vanished. In Shaper’s view, alcohol’s supposed health benefits were an artifact of number crunching. Writing in the Lancet, he lobbed the academic equivalent of a verbal grenade: “It seems that any analysis which uses non-drinkers or occasional drinkers as a baseline is likely to be misleading.”

Shaper’s ideas were soundly dismissed. “He was rounded up and beaten by his colleagues academically,” Stockwell said.

Then, in the mid-2000s, Kaye Middleton Fillmore, an enterprising scientist at the University of California, San Francisco, decided to revive Shaper’s line of research. She teamed up with Stockwell, then the director of Australia’s National Drug Research Institute. Fillmore and Stockwell pooled the findings of decades’ worth of research, but they excluded studies that lumped together nondrinkers and ex-drinkers so they could avoid the sick-quitter problem. When they did this, once again, the J-shaped curve disappeared.

Like Shaper two decades earlier, Fillmore and her colleagues were dragged through the mud. A group of leading researchers accused them of cherry-picking and faulty analysis. In a forum in which these researchers discussed the work of Fillmore and others, one researcher, Ulrich Keil, commented, “Many scientists, or so-called scientists, have great problems to discern between their emotions and the scientific data.” Meeting notes suggest that several other researchers supported Keil’s statement. Basically, scientists like Fillmore needed to both lighten up and think more rationally—perhaps by pouring themselves a whiskey.

That pro-alcohol attitude eventually yielded to mounting evidence. Fillmore died in 2013, but research from the past 10 years has corroborated her work, as studies using bigger data sets and more-sophisticated statistical methods keep flattening the famed J-shaped curve. Take one representative study, conducted by Sarah Hartz, a professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. She sidestepped the sick-quitter problem by using the lightest group of drinkers (once per month) as the reference group. She conducted her study in two large data sets, meaning that it was both statistically powered to detect small differences and possible to control for all sorts of confounding factors. Hartz found hints only of a J-shaped curve; in her study, the people least likely to die of anything weren’t the lightest group of drinkers but those who drank three times per week, for an average of about half a drink a day, which is a decidedly unsatisfying amount of alcohol. The effect was there, but barely. “I love to drink,” Hartz said, “and I worked really hard to not have this result. I stood on my head and did jumping jacks—I did all kinds of statistical acrobatics—to try to see if I could get this not to be what’s happening.”

Meanwhile, it grew increasingly difficult to pin the French paradox on wine alone. Yes, French people drink more red wine, but they also eat more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and olive oil, as well as modest amounts of meat—and in smaller portions. In other words, pretty close to the Mediterranean diet, which, as loads of research has demonstrated, bolsters cardiovascular health and may account for low obesity rates in France. It also turns out that, for some reason, the French significantly underreport heart disease on death certificates, according to a WHO investigation. Add all this up, and the French people start to seem less paradoxical. And all that research into red wine as an antioxidant superfood? You’d have to drink life-threatening quantities of wine a day to get protective amounts of micronutrients like resveratrol. Even studies that packaged resveratrol into a pill were duds.

But the bad news about drinking was only getting worse. Just as alcohol’s heart-healthy reputation was taking a hit, evidence was piling up that it was a bigger cause of cancer than previously thought. The WHO had declared alcohol a carcinogen as early as 1988, citing “sufficient evidence,” but in the years that followed, this evidence grew more and more alarming. We now know that any amount of alcohol increases the risk of cancer—particularly breast cancer. Drinking also increases the risk of liver, mouth, colon, and other cancers. And it’s not just heavy drinking: Cancer risk increases infinitesimally with each sip, in part because alcohol is metabolically converted into acetaldehyde, which damages DNA.

One team of scientists computed a “cigarette-equivalent of population cancer harm” and found that in terms of lifetime cancer risk, drinking a bottle of wine a week is like, for men, smoking five cigarettes or, for women, 10 cigarettes a week. Almost 4 percent of cancers diagnosed worldwide in 2020 were due to drinking, according to the WHO. In the U.S., that adds up to about 75,000 cancer cases and 19,000 cancer deaths each year. It’s estimated that 15 percent of all breast cancers are due to drinking. And yet, people seem blissfully unaware of this: A recent study found that only 39 percent of Americans were aware that alcohol can cause cancer, compared with 93 percent with tobacco. In another study, 10 percent of people even believed that alcohol prevented cancer.

Jürgen Rehm, a senior scientist at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Institute for Mental Health Policy Research, endorses the new stricter drinking guidelines but still believes there’s a J-shaped curve for heart disease. “Now, I think that dip is smaller than I thought 10 to 15 years ago,” he said. But, he argued, public health agencies must look at the totality of the data. Even if the current state of knowledge can’t rule out a theoretical level at which drinking is beneficial to the heart, it’s undeniable that alcohol is associated with many other killers, from car accidents to cancer. “No matter if there is this dip for heart disease, there is a risk for cancer, there is a risk for some other diseases, and those have to be weighed against each other,” Rehm said.

Hartz put it more bluntly: “Your body isn’t just the heart. We shouldn’t give people a known carcinogen to help their cardiovascular health.”

That might seem pretty obvious. But it wasn’t just data that was driving the alcohol recommendations.

The history of Big Alcohol’s involvement in the science is as complex as an aged cabernet and as potent as Everclear. Experts I spoke with pointed to at least three ways the industry has tried to shape the scientific landscape to its liking. First, it employed classic industry subversion techniques, attempting to rig significant studies. Second, it strategically amplified the work of scientists without tainting the literature itself. And third, it deftly exploited a culture war that’s been simmering since Prohibition and that molds the scientific questions being asked in the first place.

Let’s start with a brazen attempt to rig a study. Launched in 2015, the Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health Trial would have been the first large randomized control trial on moderate alcohol consumption and health. In a controversial arrangement, five major beverage corporations mostly footed the bill. However, just as the study was recruiting patients, the New York Times exposed that the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism had allowed industry leaders to review the study’s design and vet principal investigators. The study’s lead investigator and NIAAA staff even assured an industry group that the trial would show that moderate drinking was safe. Ultimately, the NIH director halted the trial, citing crossed ethical lines that left people “frankly shocked.”

But this kind of heavy-handed effort to bias science hasn’t been the industry’s most used, or most effective, tactic over the years. Instead of rigging studies directly, Big Alcohol can support scientists and promote studies aligned with its interests. Here’s how that works: In the 1960s, the industry launched a concerted effort to bankroll scientists. Major beer companies collaborated with Thomas Turner, a former dean of Johns Hopkins University medical school, to create what’s now called the Foundation for Alcohol Research. Turner’s book, Forward Together: Industry and Academia, reveals that the foundation funded more than 500 studies and awarded grants to numerous universities and researchers. Among them was Arthur Klatsky of Kaiser Permanente, who received $1.7 million in research funds in the years following his seminal 1974 study. Funding has made its way from beverage manufacturers to scientists in other ways too. R. Curtis Ellison, the prominent doctor who appeared on 60 Minutes and made the quip about the dangers of skipping a daily drink, received unrestricted “educational” donations from the industry for years.

The effects of industry funding, which can come without strings or input on the study design, are always hard to sort out. According to Marion Nestle, the NYU professor who has studied industry influence in nutrition science, “It’s more complicated than bribery.”

In the case of drinking, it is not fair to say that Big Alcohol’s money always results in a slew of outright favorable research, according to a 2015 analysis by Jim McCambridge, chair in Addictive Behaviours and Public Health at the University of York. In an analysis of 84 studies published between 1983 and 2009, McCambridge and a colleague investigated the influence of disclosed and undisclosed industry funding on the body of knowledge surrounding alcohol’s protective effects against cardiovascular disease. Their findings revealed that, except in the case of stroke, alcohol industry funding did not appear to sway the results. But in a compelling follow-up study, McCambridge and another colleague uncovered a significant bias in systematic reviews, or roundups of studies, which often guide policy decisions. Their analysis showed that all reviews by authors with ties to the alcohol industry reported health-protective effects of alcohol, while those without such ties were evenly split. So the industry isn’t necessarily buying off researchers to produce bogus science. But it can exert influence more subtly by funding research broadly, and then selectively amplifying sympathetic scientists and favorable findings.

Take the work of Klatsky, who has received industry funding but whom I wouldn’t characterize as an industry shill. He has published unflattering research showing that drinkers had elevated blood pressure, and he published an early study on alcohol and breast cancer. But it was Klatsky’s work on the cardioprotective effect that got the most attention from beverage companies, who would package up studies like his into talking points for policymakers. The industry didn’t need all studies to tilt in its favor—it had only to emphasize the positive ones to paint a skewed picture of the science (one that the American public, which, in the 1980s, was seeing an explosion in personal health advice, was all too happy to cheers to). The reality is, a small cardiovascular effect is more a biological curiosity than a basis for policy. And yet, because it legitimizes daily drinking, it has played an outsize role in the public debate over alcohol and health.

But the industry’s greatest triumph lies not in rigging studies or even selective amplification, but rather in a far more subtle and intriguing long game that has unfolded over decades, dating back to Prohibition. In the early 20th century, the temperance movement was fueled by the conviction that alcohol was a nefarious substance wreaking havoc on society, causing physical, social, and moral damage to all who indulged. This mindset led to sweeping restrictions on alcohol availability, culminating in Prohibition. Though that policy ultimately crumbled under the weight of its own failures, temperance thinking persisted, inspiring a push for broad alcohol regulation throughout the 1930s, such as strict licensing requirements for bars, bans on the sale of hard liquor, and age restrictions.

At the same time, a new perspective emerged that the problem with alcohol lay in alcoholism, a condition afflicting only a small number of people. This perspective suggested that the solution wasn’t to impose broad alcohol regulation—which would, in this view, hardly affect alcoholics—but to offer specialized assistance to the unfortunate few battling the disease. Organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous popped up, simultaneously embracing and perpetuating the fervent focus on a small cohort of people as the issue with drinking.

The newly legal alcohol industry realized the strategic advantages of the emerging alcoholism movement to its policy goals, so it quickly maneuvered to ensure that science embraced this viewpoint. Post-Prohibition, when alcohol researchers established the Research Council on Problems of Alcohol to monitor potential issues arising from legalized beer and wine, the industry quickly got involved. Struggling for funding, the council accepted industry support, which in turn influenced the types of research questions the brand-new council could ask. As a result, the group shifted its research focus exclusively to alcoholism, sidelining other issues, like alcohol’s role in crime, poverty, or other broader social issues.

Over the next few decades, the alcoholism viewpoint dominated. In 1970 it was enshrined in the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, whose mission is to investigate alcoholism as a disease, not alcohol as a public health problem. The industry didn’t have to keep shelling out money to further this viewpoint—it had baked it into the way the field had evolved. “The senior NIAAA people are not trained in public health. They just view it as an optional element of the science,” McCambridge said. The important thing to the NIAAA is helping people with addiction; the rest of us just needed to, as the industry tag line puts it, “drink responsibly.”

The industry triumphed in reframing the debate because it tapped into an even deeper cultural tension than an argument over alcohol’s health risks and benefits. Banning alcohol was part of an ongoing ideological battle between limiting personal freedoms for the sake of public health and championing personal responsibility. This debate echoes across many public health issues (Exhibit A: COVID-19). And scientists are not immune to taking sides. That’s why figures like Shaper, Stockwell, and Fillmore are accused of being finger-wagging nags, while doctors like Ellison are smeared as industry pawns jeopardizing public health for financial gain. Though the alcohol industry does not create these social dynamics, it has played a pivotal role in promoting personal responsibility not just in ads but in scientific institutions. It is a subtle and powerful sort of influence that is perhaps not remarkable but still surprising: that an industry can shape our perceptions so deeply about that glass of wine we might drink with dinner each night.

As the scientists who championed the French paradox begin to retire and the industry loses allies within academia, viewpoints like Fillmore’s and Stockwell’s are gaining traction. Yes, it has become challenging to overlook the fact that the French paradox has crumbled, the J-shaped curve has nearly disappeared, and the negative effects of alcohol are, well, pretty bad. But there’s also a cultural shift afoot—alcohol research and possibly policy are once again focusing on the broad effects of alcohol consumption on public health, not just alcoholics. Officials from organizations like the WHO can now advocate for a broader view of alcohol-related harm without facing the same level of scientific resistance. In that sense, what we’re seeing now is less a flip-flop than the demise of industry stalling tactics—and a gradual but real shift in science and culture.

OK, but maybe you clicked on this piece because you really do want to know if you should dump your martini down the sink. My read of the literature is that very light drinking (think half a drink a day) might slightly reduce the risk of a heart attack in older adults, but even then, the negative effects on overall health outweigh the benefits. The truth is that as little as one drink a day increases the chances you’ll die sooner, and heavier drinking leads to various other health and behavioral issues—making alcohol the seventh-highest cause of death and disability worldwide. From a public health perspective, reducing per capita alcohol consumption saves lives, full stop.

But from the perspective of an individual drinker, it’s less dire. The reason is that the absolute risks we’re talking about are somewhat small. To put these risks in perspective, Hartz, the Washington University researcher, crunched some numbers for me. A middle-aged man’s baseline risk of dying of any cause in the next five years of his life is 2.9 percent. If he upped his drinking from a few drinks a week to a few drinks a day, this risk would rise to 3.6 percent, or an absolute risk increase of 0.7 percentage points. What this means is that if 143 middle-aged men drink once a day, there might be, in the near-term, one additional death, while the remaining 142 men would be unaffected. Or take breast cancer. As the physician Aaron E. Carroll calculated in a New York Times article, if 1,667 40-year-old women started drinking lightly, an additional woman would develop breast cancer before turning 50, while the remaining 1,666 women would be unaffected. These are risks to take seriously, but they aren’t death sentences. On the flip side, the chance of a heart benefit from light drinking, if it exists, would be pretty small too. And any risks likely vary from person to person: An older man with a history of heart problems conceivably could benefit from very light drinking, whereas a woman at high risk of breast cancer might not. Yes, these numbers might add up to a lot of deaths and disability when we’re talking about the global population, but they aren’t reason for any individual person to panic.

Alcohol, especially wine, has basked in the warm glow of what industry insiders call a “health halo.” Consumers not only think it’s relatively harmless (which is true at low levels) but also actively beneficial (which is likely false). The updated guidelines simply mark the fading of this radiant aura, rather than signaling a return to Prohibition. “The main message is not that drinking is bad. It’s that drinking isn’t good. Those are two different things,” Hartz said. “Like, cake isn’t good for you. Getting in a car isn’t safe. Life has risks associated with it, and I think drinking is one of them.”