“Wild animals are not pets,” posted Brazil’s environmental watchdog, Ibama, on social media after what appeared to be a standard confiscation. This, however, was not just any wild animal. On April 27, Ibama had taken Filó — a capybara from the Brazilian Amazon — from wildlife influencer Agenor Tupinambá.

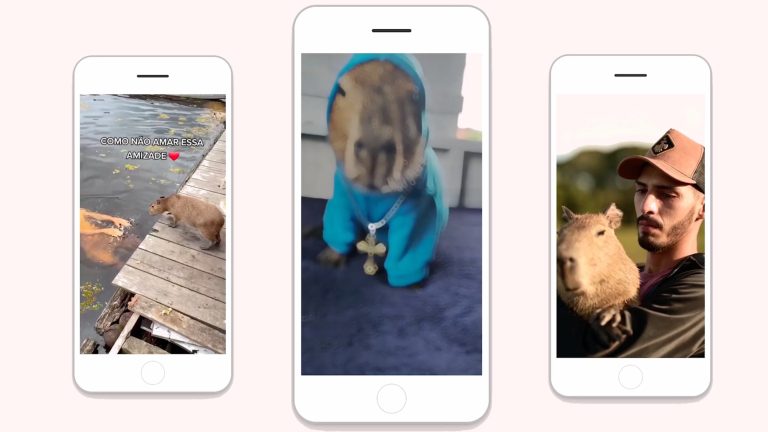

The development led to an uproar on social media. Tupinambá’s following on Instagram and TikTok blew up as supporters rallied to the cause of #FreeFiló. The influencer’s Instagram followers have grown from 10,000 at the end of last year to 2.2 million now; his TikTok following has nearly doubled to 1.9 million.

“I am deeply sorry for what is happening,” Tupinambá said in a viral post. “Only I know the pain I am feeling. I chose to be a guardian, not a criminal.” Ibama and its supporters, however, do not think this was a choice the influencer should have been allowed to make in the first place.

Tupinambá first started posting Amazonian wildlife content in 2019, while studying to be an agronomic engineer. Filó and Tupinambá became minor celebrities after posts showing them swimming, snuggling, and showering together became popular.

The duo soon drew Ibama’s attention. The environmental regulator filed a lawsuit against Tupinambá on April 19, followed by the confiscation of the capybara just over a week later. Ibama accused Tupinambá of mistreating the capybara as well as the other animals in his wildlife collection, also holding him responsible for the death of a sloth he had previously adopted. Ibama argued that inadequate nutrition had led to the sloth’s demise.

As for Filó, beyond concerns that the capybara was not living its fullest life outside its natural habitat, Roberto Cabral, a biologist at Ibama, worried about the “sanitary implications” of Tupinambá’s actions. “The influencer often broadcast himself kissing the animal,” Cabral told Rest of World. “We’ve just had a pandemic related to people’s bad behavior with wildlife.”

The outcry against the decision to take Filó from Tupinambá spread quickly. Many influential voices on social media expressed their views on the case, and the story was reported by large swathes of Brazil’s mainstream media. Joana Darc, a local congresswoman from the state of Amazonas, went as far as to stage a “break-in” into Ibama’s headquarters to “rescue” Filó. “If there was any indication that [Tupinambá] was mistreating Filó, I would have taken action against it myself, but there isn’t,” Darc told Rest of World. “I’ve followed this account closely and have never seen Filó being mistreated.”

Ibama fined Tupinambá 17,000 reals (around $3,400) for environmental violations. Using his newfound online clout, the influencer started a crowdfunding campaign that raised five times what he’d been fined.

Tupinambá said his life has been turned upside down. He told Rest of World he’d had to go to Manaus, the state capital of Amazonas — five hours away from his home — so that he could fight his case at Ibama’s headquarters in person. “I’ve missed work and suspended my university studies since all this started,” he said. He expressed surprise at how many of his followers accompanied him to Ibama’s offices in a show of solidarity. Tupinambá seems to have benefited financially from the increase in attention. Beyond the successful crowdfunding campaign, there has been an uptick in sponsored content on his previously tiny Instagram account.

Given the size and subject matter of the scandal, the campaign to free Filó soon turned political. Right-wing supporters of former president Jair Bolsonaro — who for many years criticized Brazil’s environmental regulators — joined specifically for the purpose of undermining the watchdog. “Ibama needs to review this arbitrary abuse,” posted federal congresswoman Carla Zambelli on her Instagram account.

Cabral believes Ibama acted within the law. He told Rest of World he was particularly concerned about wildlife influencers contributing to a boost in illegal trafficking. Just in Brazil, around 35 million wild animals are captured and sold each year. “Influencers stimulate the desire to have those wild animals as pets,” he said.

Wildlife trafficking’s connections to drug trafficking and organized crime also worry experts like Cabral. Rest of World found profiles across social media platforms — like the Twitter account Bichos do Tráfico (Drug Dealer’s Animals) — featuring illegally acquired birds, snakes, and monkeys carrying or surrounded by heavy weaponry.

“You are not able to show a murderer, the consumption of drugs, or other kinds of crimes on social media, so why should showing an illegal animal be allowed?”

For now, Filó’s case is moving through the Brazilian justice system. A temporary decision by a judge from a federal court in Amazonas named Tupinambá as the most capable person to look after the capybara. Filó is now back with the influencer on his farm, in the city of Autazes.

Filó’s current living conditions are much better than the cage the capybara had been relegated to while the trial was underway, said Darc. Cabral rebutted that, saying this measure would have only been temporary. After one or two weeks, he said, Ibama would have attempted to reintegrate Filó into a herd of capybaras back in the wild — something that will become increasingly harder as the animal ages.

Ultimately, said Cabral, social media platforms should bear more responsibility for posting this kind of wildlife content. “You are not able to show a murderer, the consumption of drugs, or other kinds of crimes on social media,” he said. “So why should showing an illegal animal be allowed?”