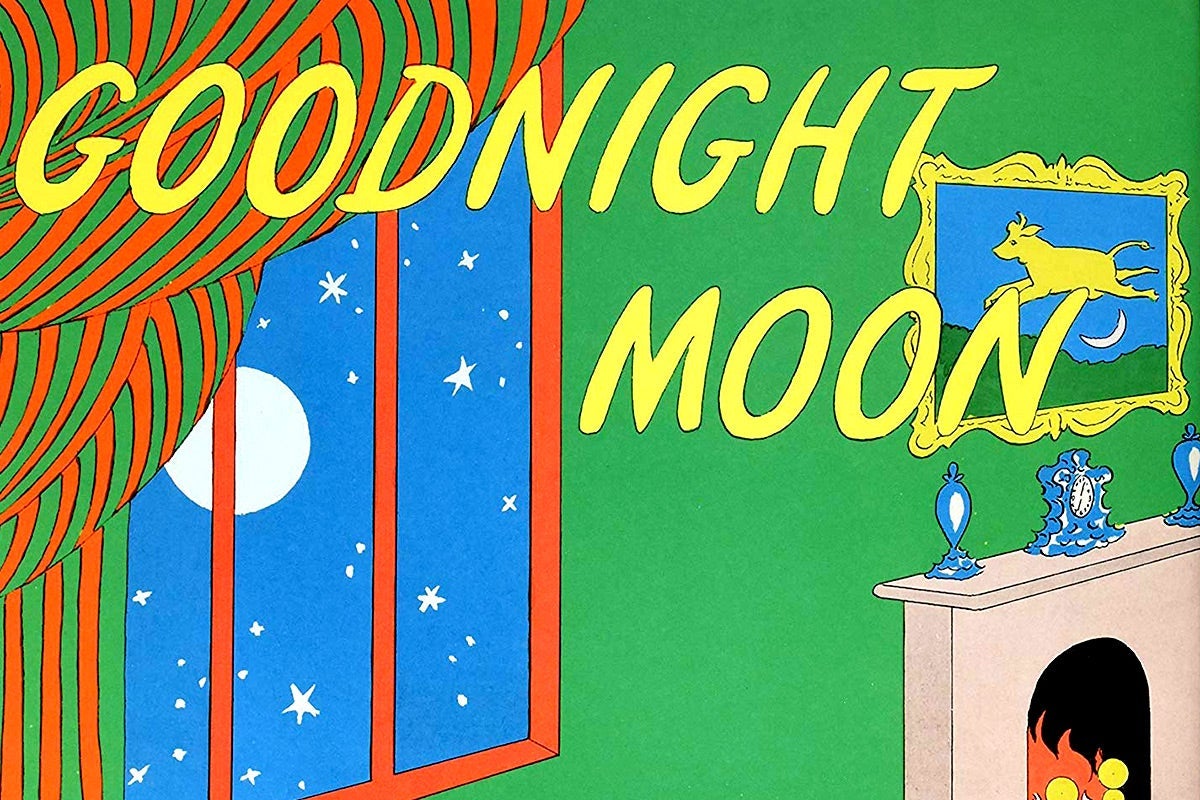

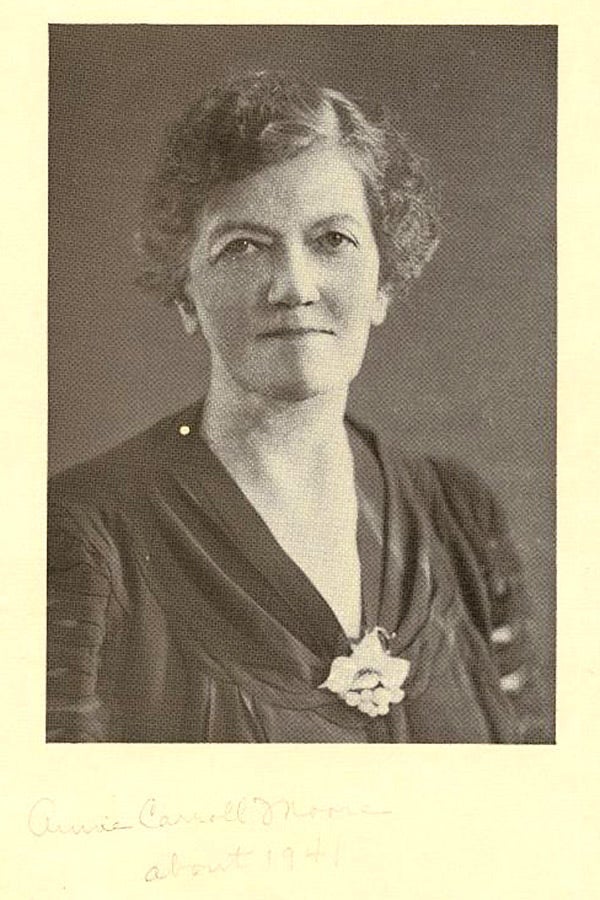

On Monday the New York Public Library, celebrating its 125th anniversary, released a list of the 10 most-checked-out books in the library’s history. The list is headed by a children’s book—Ezra Jack Keats’ masterpiece The Snowy Day—and includes five other kids’ books. The list also includes a surprising addendum: One of the most beloved children’s books of all time didn’t make the list because for 25 years it was essentially banned from the New York Public Library. Goodnight Moon, by Margaret Wise Brown, would have made the Top 10 list and might have topped it, the library notes, but for the fact that “influential New York Public Library children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore disliked the story so much when it was published in 1947 that the Library didn’t carry it … until 1972.” Who was Anne Carroll Moore, and what was her problem with the great Goodnight Moon?

As it turns out, this footnote on the NYPL’s anniversary list hints at a rich, surprising story of power, taste, educational philosophy, and the crumbling of traditional gatekeepers. Moore was appointed the NYPL’s first “superintendent of work with children” in 1906, at a time when the very idea of children even being allowed into libraries was brand-new. (Children who couldn’t read yet would gain nothing from a library, the theory went, and older children might be corrupted by all the trashy adult books.) Moore oversaw the beautiful Central Children’s Room in the library’s flagship building on Fifth Avenue. As Leonard S. Marcus writes in his biography of Margaret Wise Brown, Moore became perhaps the leading figure in popular children’s books in the first half of the century, and many of her methods seem strikingly modern. She scheduled scores of story hours for children; she encouraged any children who could sign their names to check out a book; she trained librarians drawn from a diverse range of backgrounds and then sent them out into a city of immigrant children, preaching the gospel of reading.

She was also a tastemaker whose NYPL-branded lists of recommended children’s books could make or break a book’s fortunes. “Other libraries around the country looked to the NYPL, and if she didn’t buy it, they didn’t buy it,” explains Betsy Bird, a children’s book blogger and longtime NYPL librarian who’s now at the Evanston Public Library in Illinois. “If Anne Carroll Moore didn’t like a book, she could effectively kill it.” Marcus writes that “editors, authors, and illustrators routinely stopped by to visit with Miss Moore and seek her counsel on their works in progress”; she supposedly had a custom-made rubber stamp reading “NOT RECOMMENDED FOR PURCHASE BY EXPERT,” and she was not afraid to use it.

But Miss Moore’s taste was particular. She loved Beatrix Potter and The Velveteen Rabbit and was a steadfast believer in the role of magic and innocence in children’s storytelling. This put her in opposition to a progressive wave then sweeping children’s literature, inspired by the early childhood research of the Cooperative School for Student Teachers, located on Bank Street in Greenwich Village. The Bank Street School, as it became known, was also a preschool and the teacher training facility where Margaret Wise Brown enrolled in 1935. This progressive wave was exemplified by the Here and Now Story Book, created by Bank Street’s leading light Lucy Sprague Mitchell in 1921. A collection of simple tales set in a city, focusing on skyscrapers and streetcars, it was a rebuttal to Moore’s “once upon a time” taste in children’s lit.

Anne Carroll Moore was not a fan of Margaret Wise Brown’s work. Brown, with her Bank Street training, was “looking at the mind of a child, operating at the level that a child understands,” says Bird. “She was trying to get down on their level, whereas Anne Carroll Moore placed herself above the children’s level, handing what she viewed as the best of the best down to them.”

By the time Brown’s most famous book was published in 1947, Moore had ostensibly retired, though—as Jill Lepore noted in the New Yorker in a story about Moore’s war with another children’s classic, Stuart Little—she still essentially ran the children’s section, leading department meetings even when her put-upon acolyte and successor, Frances Clarke Sayers, tried changing the meeting room at the last minute. Margaret Wise Brown wanted librarians to adopt Goodnight Moon; she even blurred out the udder of the cow who jumped over the moon to avoid offending those “Important Ladies.” But it certainly wasn’t enough for Moore, or Sayers, or the NYPL: Marcus notes that “in a harshly worded internal review, the library dismissed the book as an unbearably sentimental piece of work.” And so the book wasn’t purchased by the New York Public Library, and while children were encouraged to check out all kinds of books from the library’s extensive children’s department, Goodnight Moon was not one of them.

As Bird notes in a fascinating blog post, the legacy of Anne Carroll Moore is one that many children’s librarians struggle with. “She is the quintessential bun-in-the-hair shushing librarian,” says Bird. “She’s such an easy villain.” Her discriminating book recommendations delivered from on high represent the exact opposite of the credo pledged by most children’s librarians today: that the library’s role is to provide the widest possible array of titles and allow children to find the books they love. Yet Moore did more than anyone else in the first half of the 20th century to encourage children of all races and incomes to read. To adopt a 21st century rallying cry, Bird notes, Anne Carroll Moore “was all about diverse books waaaaaay before anyone else was.”

Perhaps in part because of Moore’s blacklisting, Goodnight Moon wasn’t an immediate commercial success; by 1951 sales had dropped low enough that the publisher was considering putting it out of print. So no one was pressuring the NYPL to stock the book, least of all Brown, who died in 1952. (Recovering from surgery for an ovarian cyst in a hospital in France, she playfully kicked her leg up, cancan-style, to show a nurse how well she was feeling; the action dislodged an embolism from a vein in her leg, which traveled to her brain, killing her nearly instantly.) The book regained popularity in the 1950s and 1960s as chains like Waldenbooks and B. Dalton grew; soon, libraries ceded their position as the primary buyers of children’s books to parents. By 1972, the book’s 25th anniversary, Goodnight Moon was nearing 100,000 copies sold a year. Perhaps it was that anniversary, speculated the NYPL’s Lynn Lobash, that spurred the library finally to stock the book.

Since 1972, Goodnight Moon has been checked out about 100,000 times from New York City libraries, placing it somewhat below the No. 10 book on the list, The Very Hungry Caterpillar. But, says the NYPL, it’s rising fast. No doubt at the library’s 150th anniversary, Goodnight Moon will have surpassed some of the more dated titles on the list, like How to Win Friends and Influence People. Sorry, Anne Carroll Moore. Margaret Wise Brown won this round.