Nearly everything we thought we knew about Robert Johnson was wrong. The biographical information that historians had gathered about the King of the Delta Blues Singers, the Grandfather of Rock and Roll, an inspiration to Muddy Waters, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones? The guy from Mississippi whose face was on a postage stamp?

Almost all of it was wrong.

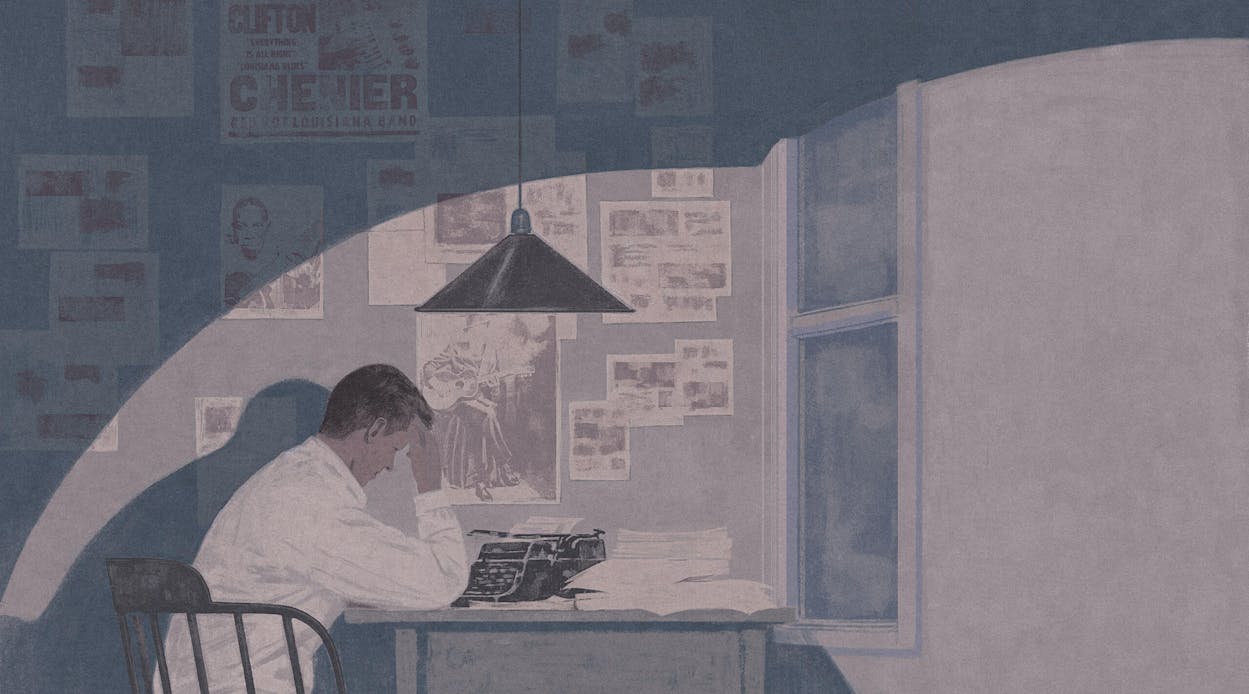

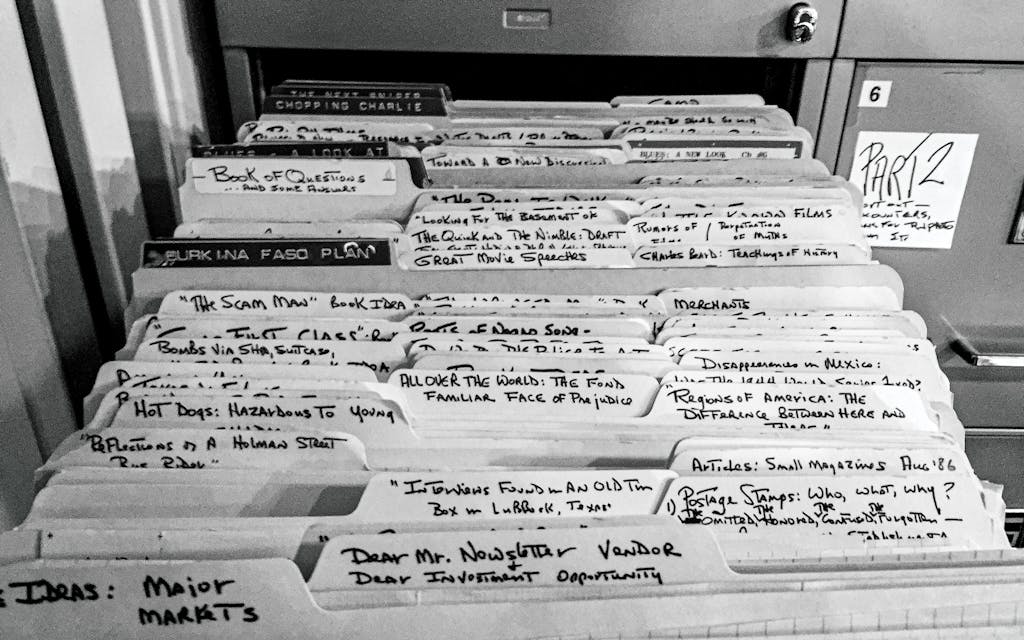

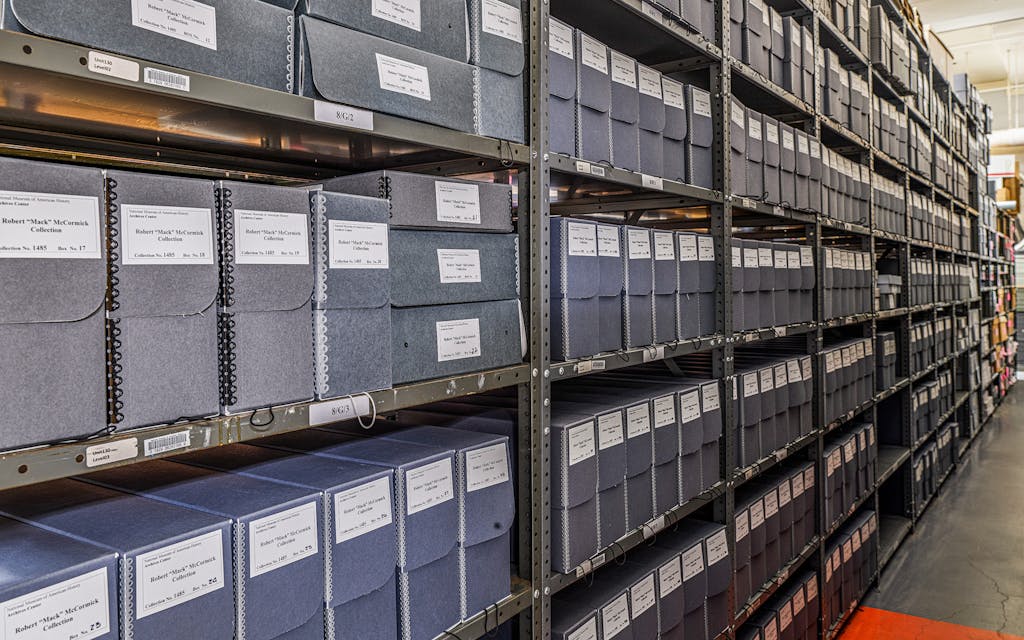

And I had the evidence in my hands: a secret manuscript about Johnson’s life found in the archive of Houston folklorist and record producer Robert “Mack” McCormick. This wasn’t just any archive. At the time, it was one of the most sought-after collections in the country—the Library of Congress wanted it, and so did the Smithsonian and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Rock star Jack White was interested in it, as were Austin’s Dolph Briscoe Center and San Marcos’s Wittliff Collections. The archive had once filled almost every corner of Mack’s home—dozens of file drawers and boxes crammed with tens of thousands of documents, photos, and recordings. Mack’s computer was full of still more files—manuscripts, plays, interviews. The archive was so vast that Mack gave it a name: the Monster.

Mack had died just a few months before, and now I was reading a manuscript he had worked on for almost fifty years—a book that countless music fans had been waiting to read for decades. Not only had Mack never published it, he had apparently never even shown it to anyone. I felt like I was reading one of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Mack was an evocative, literate writer, and in these chapters he vividly re-created the American South of the thirties, the place and time when Johnson wrote and performed the songs that made him famous. He had even talked to people who had met the elusive Johnson—a man mythologized as having sold his soul to the devil to become a virtuosic guitarist—and who remembered things Johnson had said. I was transfixed.

But the more I read, the more confused I grew. Some passages contradicted previous things Mack had written. Others seemed to defy common sense. Still others were a little too literate.

I was baffled. Mack and I had been friends, in a way. Over the course of nearly a decade and a half, I had spent countless hours with him, much of it in late-night conversation, talking about his penchant for solitude, his writing, his ability to solve seemingly unsolvable mysteries—and his inability to finish this book. We spoke of his love for big band jazz, barrelhouse piano, and the poems of Emily Dickinson, a fellow lonely recluse who still managed to find beauty and hope in the world. I liked to think I knew Mack as well as anyone did. And yet, as I pondered the evidence in front of me, I was starting to think I didn’t know him at all.

That was seven years ago. On April 4, Mack’s manuscript, Biography of a Phantom, was finally published, more than five decades after he started it. But it’s very different from the pages I held in my hands back in 2016. In parts of the book, Mack’s presence outweighs Johnson’s—and not to Mack’s benefit. By the last page, Mack has become the villain of his own life’s work.

Mack’s favorite Dickinson poem begins, “This is my letter to the World that never wrote to me.” If you’re familiar with the poem, you know that it ends, “Judge tenderly—of Me.” As Mack’s friend, I’m going to try to do that for him. Though he made it really hard, because a lot of what I thought I knew about Mack was all wrong.

The first time I rapped on Mack’s door was on a hot September afternoon in 2001. Two small gargoyle tchotchkes and a devil figurine stood puny sentinel by the front window. A handwritten note taped to the door read “Do not knock until 1 pm or later.”

I was there because of Robert Johnson. I’d first heard of him when I was a teenager living in San Antonio, probably from an article in Rolling Stone. Johnson’s songs, which conjured up a dark cosmos of hellhounds and crossroads out of nothing but his voice and acoustic guitar, had little in common with the modern rock I spent most of my time listening to. I remember poring over the liner notes of the 1961 Johnson collection, King of the Delta Blues Singers, and being surprised to see that he had recorded most of the songs in 1936 at the Gunter Hotel, just a few miles from where my family lived. Over the years I read a lot about music, and almost anytime anyone wrote anything about Johnson or Texas blues, Mack’s name came up. He was the man who had uncovered most of what we knew about Johnson’s life but never managed to finish his book on him. So when I discovered, in 2001, that Mack lived in Houston, I wrote him a letter saying I wanted to take a road trip with him to San Antonio to talk about his search for Johnson and write about it for Texas Monthly.

Mack wrote back one of the strangest letters I’ve ever received. “A quoggy irony has descended,” it began, sending me to the dictionary. He said he wasn’t interested in talking about Johnson—he had recently been sued by Johnson’s heir and was wary of saying anything publicly. But he was getting old, and he was worried about his life’s work being lost to time. Come to Houston, he said, and profile the Monster. I jumped at the chance.

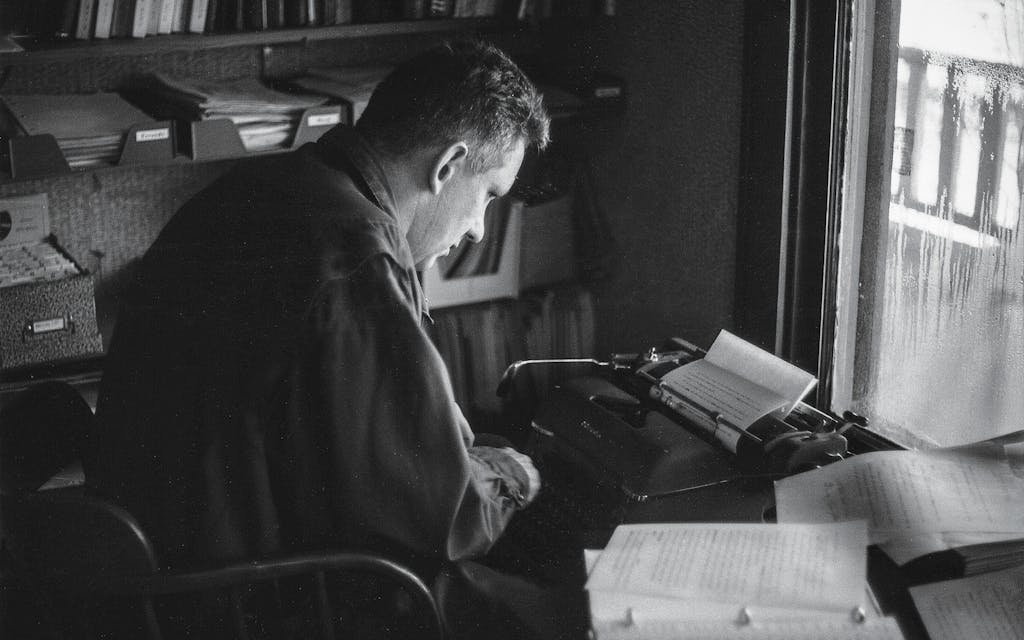

Mack opened the door and welcomed me in. He was 71 and slow moving, with white hair and large ears. His office was lined with towers of long, old-fashioned file cabinets; down a short hallway, the back room was packed with shelves holding boxes of reel-to-reel tapes and still more file drawers. Two of the tall cabinets were bound by steel chains and held fast by padlocks.

Mack lived alone, and we sat in the living room, which was cluttered with stacks of papers, books stuffed with Post-it notes, and banker’s boxes full of files. A guitar once played by the bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins leaned against a wall. I looked around and shivered. I’d never felt so close to so much hidden history.

I spent a couple of days with Mack, talking about his long career. Well, I listened, Mack talked. He was a spellbinding storyteller, a bohemian Renaissance man spinning from one topic to another as I struggled to keep up. He’d start with Blind Willie Johnson and pivot to the Voyager spacecraft and wind up with the Chuck Wagon Gang. He had a wry sense of humor and wasn’t afraid to make fun of himself. He was always ready to show me some of the unreleased tapes he’d made of seminal blues musicians such as Mance Lipscomb and Grey Ghost or files with names like “Black Rodeo” and “Zydeco: How is it spelt?”

I couldn’t get enough. Mack would make us gin and tonics, and we’d talk until it was time for dinner. On the way out the door, he would stop, turn, and call out loudly, “We’ll be back in a little bit, Lorraina!”—just in case someone outside was watching. He was so worried about thieves that he claimed he kept some of his archive at a secret spot in the mountains of Mexico.

He talked about his family, his health, his unpublished works. He was manic-depressive, he said, and had “some destructive block” that kept him from finishing his books. This didn’t prevent him from starting new projects, which he did all the time. “I’m the king of unfinished manuscripts,” he said, noting at least six, including the Johnson book, which he didn’t want to talk about. Except when he did. It was clear that Mack was still obsessed with telling Johnson’s story.

Mack was an only child—born in Pittsburgh, in 1930, to parents who were X-ray technicians. They separated when he was two, and he was raised in different cities, mostly by his mother, with whom he was close. Mack changed schools often and didn’t have a lot of friends; he spent time glued to the radio, listening to the music of the era. He and his mom moved to Houston when he was sixteen, and Mack, a shy kid and music nerd, whiled away the hours reading, writing, and listening to jazz.

The birthplace of jazz wasn’t far away, so Mack hitchhiked to New Orleans, where he met an inscrutable record collector named Orin Blackstone, who was working on a set of books called Index to Jazz. Blackstone asked the teen to be the Texas editor of the final two books and find jazz and blues 78-rpm records made in the state. The meeting changed Mack’s life. He had never liked being an introvert, and now, working as a field researcher, he was pushed to connect with people, hitching out into the rural areas around Houston and knocking on doors, looking for old records.

In 1947 his mother, who worked at an osteopath’s office, introduced him to one of her patients, Bill Quinn, who owned the music label Gold Star Records, and the man invited the tall, thin kid to a recording session. That day, Mack met Lightnin’ Hopkins, who recorded for Gold Star but was mostly unknown outside Texas. Mack was getting an education in the Houston music demimonde, and he dropped out of high school and began promoting big band shows. He also became the Texas correspondent for DownBeat, the jazz magazine. His writing was smart and funny—in a review of a Stan Kenton show he noted “the absolutely tasteless trumpet acrobatics of Maynard Ferguson.”

But Mack had been suffering from bouts of anxiety and even nervous breakdowns, which probably led to his inability to hold a job for long. He spent his twenties drifting among posts—barge electrician, short-order cook, cabbie. Driving a taxi took him all over Houston, where he heard all kinds of music: blues, swing, Czech songs, conjunto. He began recording some of it, and in 1959 he put a mic in front of Hopkins. The brilliant but mercurial Hopkins brought out an untapped ambition in Mack, who was eager to bring the bluesman to the burgeoning folk audience. And it worked. Mack produced and wrote the liner notes for several Hopkins albums and helped him get gigs in front of integrated audiences in Houston. Within a year Hopkins was playing on a bill with Joan Baez and Pete Seeger at Carnegie Hall.

Mack’s work with Hopkins drew the attention of a young California blues fan named Chris Strachwitz, who wanted to start a roots-music record label. In 1960 Strachwitz came to Houston and met up with Mack. The pair drove around the rural area northwest of Houston knocking on doors and looking for musicians to record. They heard about a 65-year-old sharecropper and guitar player named Mance Lipscomb, found him in Navasota, and persuaded him to record right then. Lipscomb’s album was the first release for Strachwitz’s Arhoolie Records (the label would eventually put out hundreds of albums), and Mack, again, wrote the liner notes. That LP helped turn Lipscomb into a folk darling; over the next few years he signed to a major label and then appeared at California’s Monterey Folk Festival, alongside the likes of Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary.

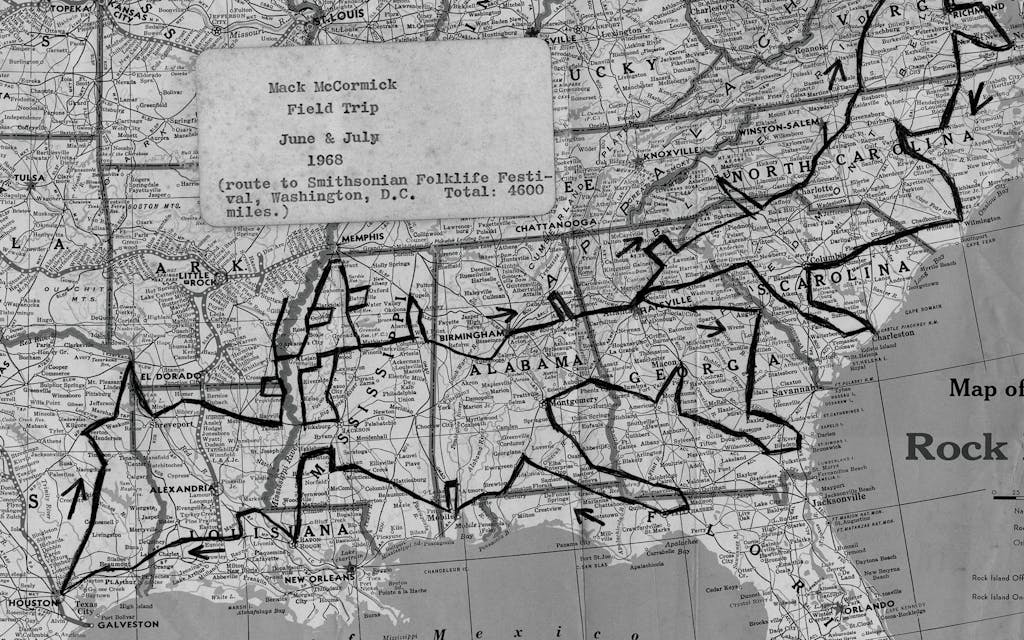

Mack loved knocking on doors and knew that what he was finding behind them—the music, the musicians, the history—needed to be documented. So he began collaborating with the British scholar Paul Oliver on a book tracing the origins of Texas blues. The idea was simple: Mack would do most of the research, and Oliver would do most of the writing. Mack was so enthusiastic about his task that in 1960 he took a job as a census taker in Houston’s Fourth Ward; after asking residents his official questions, he would ask them what he really wanted to know: did anyone in the house play music? He would head out into East Texas, approaching locals in places where, he wrote at the time, “Suspicion and indifference are the typical masks which confront a stranger.” Depending on the situation, he could be gruff like a cop or earnest like a schoolboy. He would stop in the county seat, approach a group of men playing dominoes, and ask if he could watch. “Get friendly with people,” he told me. “After a while, ask a bunch of questions at once, get them agitated, sit back, and they start answering them.” He was constantly searching out talent; if he was sufficiently impressed by musicians he saw on a street corner, he’d record them. At the end of the trip, Mack would label his tapes and type up his notes and put them in folders—and then into the Monster.

He went places no one had ever searched before. In Wortham he tracked down the sister of Blind Lemon Jefferson, who told him that her brother would walk through the streets playing the guitar, using the echo of his notes to find his way, much as a bat used sonar. Mack tracked down stories of the bluesman Lead Belly near tiny De Kalb and found people who he said remembered the singer’s early days—including relatives of two men he had killed. Mack recorded cowboy songs, truck-driving songs, dirty songs. He even started his own record label, but he put out only one album before it fell apart.

Mack’s mental health wasn’t getting any better. He would be struck by, as he wrote Oliver, “bizarre funks which overcome me from time to time bringing apathy and leaving me in disorder.” Mack found some solace with a Houston woman named Mary Badeaux, whom he married in 1964. And his reputation as a folklorist continued to grow. In 1965 he was asked to bring a prison crew to sing work songs at the Newport Folk Festival, in Rhode Island. He put together an ad hoc group of ex-convicts living in a Houston halfway house who chopped wood while they sang. Mack would later claim that when Bob Dylan and his band refused to quit jamming during the sound check, Mack unplugged the PA. Soon the Smithsonian hired him to put on festivals all over the country featuring artists as diverse as the Georgia Sea Island Singers and Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys.

But one musician captivated him more than all the others.

Mack had first heard of Robert Johnson in 1946, when Blackstone showed him one of his Johnson 78s, but he didn’t become a fan until he dove into the same 1961 compilation that got me started. Little was known at the time about Johnson other than the claim, sometimes attributed to the bluesman Son House, that Johnson had sold his soul to the devil in order to play so well. During Mack’s travels, he had started to gather information on Johnson, including, in 1969, his 1938 death certificate. By then Mack had become obsessed with, in his words, this “dark young fury that reveals something about the American experience.”

Mack ventured to towns and cities in Mississippi that the singer mentioned in his songs and buttonholed total strangers. In 1970 he traveled to tiny Robinsonville, just south of Memphis, which he had been told was Johnson’s hometown. Mack climbed onto a yellow school bus that served as a “rolling store” for sharecroppers and began asking about Johnson. He was met with blank stares until a man said, “You mean Robert Spencer.” Before Mack knew it, he found friends and distant relatives of the guitarist, who was known by more than one name. These people knew about Johnson, his brother, mother, and sisters. Mack also interviewed a woman named Virgie Mae Cain, who had had a child with Johnson named Claud and gave Mack a photo of her son. In Greenwood, Mississippi, where Johnson died, Mack found several people who said Johnson had been poisoned by a jealous husband.

Johnson’s sisters were initially suspicious of the pushy white historian, but he charmed his way into their homes, and they began filling in the details of their brother’s life.

Step by step and phone call by phone call, Mack managed to track down two of Johnson’s sisters, Bessie Hines and Carrie Thompson, who lived in Maryland. Both were initially suspicious of the pushy white historian, but he charmed his way into their homes, visiting several times in the summer of 1972. The two began filling in the details of their brother’s life: when he was born, who his parents were, where he grew up. There was even a casual reference to the recording sessions that would turn Johnson into a legend: Thompson told Mack that her brother once excitedly asked her, “Sister Carrie, you know where I been?”

“No,” she said, “where on earth have you been?”

“I been to Texas,” he replied. “I made some records.”

The sisters gave Mack details that fleshed out their brother’s story: how he bought a cheap guitar as a teenager, how he’d play on the levee at Robinsonville, how his first wife had died in childbirth—and how it took him a long time to get over it. The sisters loaned Mack several photos, including one of young Johnson with Thompson’s son Lewis in a white sailor’s uniform. Mack also got them to sign a contract giving him permission to use their stories in a book.

In late 1972 he returned to the house in Houston that he shared with Mary and their infant daughter, Susannah, and gathered the results of his staggering research, some of the first known biographical details about American music’s most elusive persona. Now all he had to do was write.

By around 1975, Mack had completed a first draft of Biography of a Phantom. But he also had company on Johnson’s trail, another blues researcher named Stephen LaVere, who talked the sisters into signing a new contract. LaVere would oversee the estate in exchange for half of all the money that came in. As executor, he would later release two photos of Johnson, one showing him wearing a pinstriped suit and hat, another with a cigarette in his mouth. LaVere also went to Columbia Records and got the label to put together a compilation of Johnson’s entire recorded output—songs from that 1961 album as well as a second one from 1970, plus alternate takes. When Mack found out, he threatened to sue. Columbia held off on the collection’s release, a delay that would go on for years.

Some writers would have taken the competition as a prod to finish their book. But not Mack. He was a perfectionist who needed to square every detail and connect every dot. He would get frustrated with the many contradictions he had found in Johnson’s story—and impatient with his family. He would tell Mary to stop cooking; the smells were interfering with his work. He would tell Susannah to stop playing; she was making too much noise. He would sink into moody funks and stop working altogether.

He put the book aside for another obsession: Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas, who had recorded a series of buoyant reels, jigs, and early blues songs in the twenties. No one knew anything about him, other than that he was a hobo who traveled Texas by train playing guitar and some kind of pan flute. But Mack dived deep, driven by the conviction that a guitar-playing vagrant he’d met on a downtown Houston street in 1949 was Thomas. One of Thomas’s songs mentioned stops along the railroad in northeast Texas, and Mack knocked on numerous doors in small towns there, playing recordings of the singer’s voice for elderly African Americans, trying to place the accent. His research finally led to a farm in Upshur County, where Thomas had been born. Mack sat down and wrote the liner notes for a compilation album of Thomas’s songs, which came out in 1975. The eloquent and deeply detailed essay received almost as much attention as the music. “Mack had the gift of imaginative transference,” the celebrated music writer Peter Guralnick told me, “the ability to think, feel, and see beyond the limits of your own narrow world.” The rock critic Greil Marcus called the essay “the best notes of their kind I have ever read.”

But Mack’s manic depression was getting worse. When he was “up” he would go out into the world and talk to people—and get into late-night arguments with cops in Dunkin’ Donuts. When he was “down” he would lose all his energy and withdraw further. The Texas blues book he had been working on with Oliver was shelved, but Mack insisted that the Johnson book was “undergoing final editing.”

On his good days, he could be extraordinarily generous. In 1976 Guralnick visited Mack and interviewed him. Mack told Guralnick what he had learned from Johnson’s sisters and even showed him the photo of Johnson and his nephew that few had ever seen. Guralnick wrote about Mack’s findings in Rolling Stone, the first time many of the facts of the bluesman’s life became public.

Thirteen years later Guralnick released a book on his own obsession with Johnson called Searching for Robert Johnson. The book gave an even more detailed biography of the bluesman—again, largely based on Mack’s investigations. A year later, in 1990, Columbia finally decided to ignore Mack’s threats and released its long-planned compilation, a two-CD box set called Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings. The album eventually sold more than a million copies, won a Grammy, and made Johnson a household name. But Mack’s name was completely absent from the credits and the voluminous liner notes. The record and Johnson’s increasing fame earned a small fortune for his estate and for LaVere.

And Mack’s book was still nowhere to be seen. By this point he was spending most of his days and nights hidden away in his Houston home. He and Mary had split, Susannah had left for college, and Mack began to withdraw from virtually everyone while he worked on various manuscripts, watched movies, and wrote letters. The house lights would burn until four or five in the morning. He wouldn’t put out his garbage can until late, convinced that thieves would go through it, looking for discarded pieces of the archive.

My Texas Monthly profile of Mack came out in 2002. The headline, “Mack McCormick Still Has the Blues,” was a nod to his depression and isolation, but the story was largely a wide-eyed, gee-whiz look at a man whose whole life had been about making connections—among ideas, artists, and other human beings. “Each of us are connected by an infinite number of threads,” he told me, a thought I considered particularly beautiful.

And there were days when Mack still reveled in making those sorts of connections. Numerous people visited him, including archive directors hoping to host the Monster and writers and researchers hoping to tap into his wisdom. He genuinely enjoyed holding court with his callers. “He was generous with me, almost to a fault,” said music scholar Ted Gioia, who first visited Mack in 2005. “He shared proprietary information from his own research—things other writers would have retained for their own publications.”

Almost everything we knew about Robert Johnson, Mack believed, was wrong, because we were looking at the wrong Robert Johnson.

Mack and I stayed in touch, and when I visited Houston, I’d stop by and take him to dinner. He had started again in earnest on the Johnson manuscript, and he told me some startling things. He had been going back over his old interviews and field notes and had begun to take more seriously nagging suspicions he’d long had about Johnson. He said he was having serious doubts that the man whose trail he had discovered back in 1970—the Robert Johnson from Mississippi—was, in fact, the Robert Johnson who’d recorded those immortal songs in Texas. There was no proof, he said—no contracts, no letters.

He was troubled, too, by the authenticity of Johnson’s death certificate; it stated that the dead musician was a banjo player who probably died of syphilis. “A syphilitic banjo player!” Mack snorted. He said he had found seven other men with the same name who also played music in Mississippi at that time and asserted that everyone else at Johnson’s sessions in San Antonio and Dallas came from Texas or nearby. Why would the producers bring an unknown kid all the way from Mississippi to record? Mack didn’t know of any evidence that Robert Johnson ever played in Texas otherwise. It would make much more sense that the Robert Johnson who recorded in Texas already lived in Texas, was perhaps from Texas. Almost everything we knew about Robert Johnson, Mack came to believe—which is to say everything Mack had discovered about Robert Johnson—was wrong, because we were looking at the wrong Robert Johnson.

Mack was starting to think of his Johnson manuscript as being two distinct entities. What he eventually came to call “Book One” would focus on the Wrong Man, the Mississippi blues musician whose story and likeness Mack had brought to the world through his research—but who, as far as Mack could tell, had never recorded a note. “Book Two” would focus on the Right Man, the musician in Texas who had recorded those famous sides in San Antonio and Dallas. He was concentrating on Book Two now, and in his manic phases he would write for hours on end. There wasn’t much biographical information on this Robert Johnson, but Mack said that while going through his voluminous files, he had found interviews he’d done long ago that cast light on this figure.

I was fascinated by all of it and flattered that Mack was entrusting me with this secret knowledge. I thought I was going to be the writer who would reveal the shocking truth about Robert Johnson to the world—something any music journalist would dream of getting the chance to do.

But I wasn’t Mack’s confidant for long. In 2007 I spent a couple of days in Houston working on a story about Lightnin’ Hopkins. I was thrilled to be able to give Mack some credit for all he did for Hopkins, and I borrowed a few of the vintage LPs he had produced to use as art for the story. Mack made me promise that we wouldn’t make any copies of the album covers—which I readily agreed to, thinking he was talking about reproductions that could be bootlegged. Days later he flew into a rage when he learned that we had made copies of the LP covers for our page proofs. I tried to reason with him, but the next morning I found a six-minute voice mail on my office phone threatening to sue me and Texas Monthly if we used photos of any of his LPs. The tone of the message was implacable, and I could tell he was reading from a script. I called to try and talk sense to him, but he wouldn’t pick up the phone. We pulled the art.

Over the next four years I called occasionally, but Mack never answered. As I tried to figure out how our friendship had fallen apart, I began to think that maybe his troubles were deeper than I had known—and that I had been blind to them. I had always viewed Mack as a lonely, pioneering folklorist who meant well but was undone by his idiosyncrasies as well as a more business-savvy rival, Stephen LaVere. When, in 1998, LaVere and Johnson’s son, Claud, sued Mack, claiming he had stolen photos from the family, Mack swore that he’d lost the photos, and I believed him. (The suit was eventually dropped, and the pictures went unreturned.) I knew Mack had fallen out with both Oliver and Strachwitz, and when he told me that it was just the sort of thing that sometimes happens between longtime friends who no longer see eye to eye, I believed him.

But I’d soon learn that Mack was in the habit of torpedoing virtually every relationship he’d ever had—especially when the friends in question wanted to help him. One of Mack’s closest friends was Roger Wood, an author of several music books and an English professor at Houston Community College who, like Mack, loved Emily Dickinson. For more than a decade, the two had a monthly dinner date and would talk for hours about music, poetry, and history. About a decade ago they started discussing a photo book that Mack wanted to put together about musicians he had worked with at a 1971 folk festival in Montreal. “I’d really like to get something published here before it’s too late,” Mack told his friend.

But then, not long after, Mack started hinting that maybe he didn’t want to work on the book after all. One night Wood went to Mack’s house for dinner. “He was waiting for me,” Wood remembers, “and he was angry.” Mack hectored Wood, accusing him of thinking he could do something that Mack couldn’t or wouldn’t do. Eventually, Wood said he couldn’t take it anymore. “I’m out of here,” he said, to which Mack replied, “If you leave, don’t come back.” Wood left. A few weeks later, after he’d cooled down, Wood called Mack, but got no answer. He wrote Mack a letter and called again, but Mack didn’t respond to any of it. They never spoke again.

Wood was disappointed by all of this, and more than a little hurt. But he wasn’t entirely surprised. He says that several people, including Strachwitz, had warned him that Mack would inevitably subvert any project they worked on—and their relationship. “We all knew—and Mack encouraged us to see—that he was a victim of a disease,” Wood told me. “But to me there was will involved, something self-sabotaging. There was some real anger in Mack.” Wood thinks Mack resented how people like him could easily move through the professional world when they had never done the kind of research Mack did. “He had this punk ‘f— you’ attitude toward the academic establishment, the publishing establishment, the music history establishment.”

“My entire life I watched the cycle repeat,” his daughter, Susannah, told me. “It didn’t matter who he dealt with, he would alienate them, and they would alienate him. He couldn’t make decisions; he got hung up on minor details. It was his illness, it was his personality, it was his age.”

The man who believed that we’re all connected “by an infinite number of threads” was too debilitated by depression and bitterness to hold on to that conviction for long. The tragedy of Mack’s life was that he severed so many of the connections that people desperately wanted to make with him.

In January 2012, I made one of my occasional calls to Mack, figuring that the phone would, once again, ring and ring and then I’d get sent to his answering machine—even though he almost certainly was sitting nearby in his recliner. To my surprise, this time he picked up. “Mack, how are you doing?” I stuttered. “Getting older is a matter of getting ground down,” he replied. Mack told me he was writing a lot of plays, including one about Emily Dickinson. He was still working on the Johnson manuscript, which was hundreds of pages long. He said he was terrified about going down in history as a footnote to the Johnson story. When I visited him a few months later, I noticed that he was weak, stooped over, and barely able to walk. When we went out to a restaurant, I had to hold his arm and help him to the table.

Mack had always been paranoid about someone possibly stealing his materials, and, in 2013, someone did. Kind of. A year or so earlier, Mack had been contacted by the journalist John Jeremiah Sullivan, who was interested in writing some kind of story involving Mack and the Monster and said he might be able to help him finish the Johnson manuscript on the New York Times’ dime. When Sullivan came to visit, they spoke about various topics, including two obscure female blues musicians named Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas, whom Sullivan said he was particularly interested in, especially after Mack said he had interviewed Thomas. Mack even gave Sullivan some of the notes he’d made about his 1961 searches that revealed her name was L. V., not Elvie. A researcher named Caitlin Love was brought in to help with the project. But after a couple of weeks Mack grew frustrated by what he said was her tendency to disappear behind closed doors for hours at a time. Mack soon terminated his relationship with her and Sullivan—because, he told me, he was convinced that Love had hidden ragweed in his AC system in order to render him groggy.

This was a ridiculous accusation, a sign of just how unhinged Mack could be. But Love did do something problematic. She took photographs of the transcription and notes that Mack kept of the interview he had done with L. V. Thomas more than fifty years before—photos she would eventually pass on to Sullivan. In 2014 the New York Times Magazine published Sullivan’s story on Wiley and Thomas—which included a conversation with Love about how she took the photographs—on its cover. The linchpin was that interview transcript. Sullivan wrote, “I admired the bravery of her act of quasi-theft, feeling strongly that it was the right thing to do.” He also wrote a succinct version of a complaint many researchers had had against Mack for decades: “You’re not allowed to sit on these things for half a century, not when the culture has decided they matter.”

Sullivan’s story was remarkable. He and Love engaged in some very Mack-like research, knocking on doors in Houston and finding people who helped them rescue two neglected blueswomen from obscurity and bring them to life. But it also prompted a major scandal in journalism circles, with Susannah telling the New York Observer that she was “appalled” by Sullivan’s actions. (Sullivan and Love declined to be interviewed on the record for this story.) Though I was furious with Sullivan, too, I shared his frustration. I also knew how paranoid Mack could be—and how sneaky. “Had he deliberately left these papers in the open in order to test her?” he wrote in the story. “It was hard not to feel that he arranged for this little disclosure.” I, too, had little doubt Mack had purposely tempted Love by leaving the file in plain view.

Mack, who believed that we’re all connected “by an infinite number of threads,” was too debilitated by depression and bitterness to hold on to that conviction for long.

Amid all that, Mack was still writing, but he had been having trouble swallowing, and in 2015 he received a dire diagnosis: cancer of the esophagus. I visited him that September and asked how he felt. “Terminal,” he replied. He lay in his tan recliner, the seat from which for decades he had received pilgrims. His hair was bright white, his eyes dark and sunken. An old white T-shirt sagged off his gaunt frame. At his request, I agreed to be his literary executor, to take care of his archive and his manuscripts, including Biography of a Phantom.

To my surprise, he even gave me a couple of the early chapters to read. I took them home and was stunned by how good they were. The writing had a firm sense of place, and it was full of detail and dialogue. I could picture Mack in Mississippi, talking to strangers, asking questions. I told him how impressed I was. “Thank you,” he said, sounding genuinely pleased. “That’s very encouraging. No one’s said that to me before. Of course, no one’s had a chance to read it.” He was slurring his words, his body drunk on morphine. It was one of our last conversations.

Mack’s final days were a mess of recriminations, fear, and loathing. He caught a contagious bacterial infection called C. diff that kept all visitors away. He became convinced that everyone was out to get him—his daughter, his caretaker, me. At one point he asked his caretaker to marry him so his archive and manuscripts would be safe from the thieves who were waiting for him to die. When she said no, he asked her to find him a bride on Craigslist. She refused. He spent his final days watching the Animal Planet channel until he slipped into unconsciousness. He died on November 18, 2015. I delivered the eulogy at his funeral and read Dickinson’s “This Is My Letter to the World.” Many of the mourners in the room knew those words. He had tried the tenderness of each of us.

The day after Mack died, I drove to Houston to help Susannah and her husband, Dave, move the archive to a storage facility. We were astonished at how much stuff was in the Monster. Mack had more than twenty file cabinets, each of which was jammed with documents. There were also about six hundred reel-to-reel tapes of music and thousands of photos and negatives.

I felt privileged to be going through these files, as if I were a witness to history. When I got to drawer number four, I found an eight-by-ten envelope containing a dozen prints. I flipped through them and came upon one of a man in a white sailor’s uniform. Next to him stood a shorter, smiling man in a pinstriped suit and hat. I stared at his face. It was a familiar smile, a familiar suit, and the hat was set at a familiar angle—on the head of Robert Johnson. In my hand I held one of only three then-known photos of Johnson, a photo that few people other than Mack, Johnson’s sisters, and Guralnick had ever seen.

I began to uncover other secrets too. In the Lemon Jefferson file was a letter from the bluesman’s sister complaining that Mack had failed to return a photo of Jefferson that he had promised to send back. I also found a letter from Claud’s mother, Virgie, asking for a photo of her son she had given Mack. There was a clear pattern here, and it seemed likely that Mack, despite his protestations, had just refused to return the photos Johnson’s sisters had loaned him back in 1972.

And it turned out that Mack was no stranger to swindling. Around that time, Susannah sent me a text. “Did you know my dad was arrested for passing phony checks when he was 19?” She had discovered the evidence in one of his old “Memorabilia” files. Mack had used six different names as he cashed bad checks until he was finally caught. He did time in the Harris County jail. Clearly, there were layers of darkness in Mack’s life that even those of us closest to him knew nothing about.

I organized the twelve typewritten chapters of Biography of a Phantom, a.k.a. Book One (The Wrong Man), as well as the voluminous computer files of the untitled Book Two (The Right Man) and finally sat down to read. The manuscript of Biography of a Phantom was long—some 550 typewritten pages—and vividly reported and written. Mack wrote in detail about finding Johnson’s sisters as well as Virgie. She told Mack that Johnson told her how he wrote his songs. “They come to me in a dream,” he had said. The manuscript was every bit as thrilling as I had hoped, even if it was the story of a wild-goose chase—a biography of a man who, at least according to modern-day Mack, probably hadn’t actually written and recorded all those immortal songs.

Mack asked his caretaker to marry him so his archive and manuscripts would be safe from the thieves who were waiting for him to die. When she said no, he asked her to find him a bride on Craigslist.

The chapters in Book Two about the man Mack seemed convinced was the real Robert Johnson weren’t nearly as well written, though Mack had plenty of details. He had tracked down Marie Oertle, the wife of the record label salesman Ernie Oertle, who had driven Johnson from New Orleans to San Antonio for his first recording session. It turned out that Marie had gone along too and not only had paperwork from the trip, she also had memories about the soft-spoken musician—how he dressed, talked, played. She explained to Mack how Ernie had first picked up Johnson when he was hitchhiking by the side of the road near Lufkin, and after Johnson passed an audition in New Orleans, the trio set out for San Antonio, Johnson often taking the wheel for stretches, as if he were a chauffeur. They stopped in La Grange and met up with Blind Willie Johnson, who was playing at a revival.

Mack’s interviewees revealed all sorts of fascinating details to him about the Texas Robert Johnson. Al Dexter, who had auditioned for Oertle at the same time, complimented Johnson’s guitar playing. Tony Garza, who worked for the record label, remembered taking Johnson to breakfast and being surprised when he ordered his eggs “picante” and said “gracias” to the server. The session engineer, Vincent Liebler, an experienced studio hand, was in awe of Johnson. “He struck me as special,” he told Mack.

But I kept coming upon things that didn’t make sense. Mack had written different versions of the same event, and the details shifted from one telling to another—sometimes dramatically. And the dialogue—well, it was a little over the top. In La Grange, where Robert met Willie Johnson, Willie said to Robert, “You got the Devil’s music in you and it ain’t welcome here.” Robert replied, “I expect so. I done sold my soul to the Devil.”

That sounded like bad dialogue from a bad play. Unnerved, I put down the manuscript and began going through Mack’s files, where I found notes from some of these interviews. Mack had indeed found Liebler, in 1978. But according to his notes, Liebler “doesn’t recall RJ too well.” Mack located Garza in 1973. “Not too good a source,” Mack wrote. “Garza very uncertain.” I came across an email that Mack wrote to a friend in Dallas, in 2003, asking for help tracking down Marie Oertle: “She’s the one I need to learn about.” But Oertle had died in 1994. It seems likely that he never spoke to her. Mack found Dexter in 1980. Yet his notes indicate that Dexter recalled little except that Ernie Oertle brought a “colored boy” from Mississippi to San Antonio to record—which seemed to confirm that Johnson had, in fact, come to Texas from Mississippi.

It was clear that Book Two was as full of invented dialogue and scenes as any of Mack’s plays. I was shocked at my gullibility, embarrassed at my willingness to believe every tale this storyteller had told. Could it really be that Mack—angry and bitter at a world that had lionized Robert Johnson and never given his most enterprising biographer his proper due—had spent his final twenty years trying to destroy the Robert Johnson he had helped discover, telling anyone who would listen—Gioia, Sullivan, Susannah, Wood—that we had the wrong guy?

I went back and went through the Monster again. The clues were everywhere, but I had overlooked them in my excitement—and ambition. One of Mack’s proposed titles for Book Two was telling: Who Killed Robert Johnson? A Subjective Biography and Wayward Autobiography.

Susannah wasn’t entirely surprised by any of this. “The last ten years before my mother died and then afterward, he was living in a fantasy world. Anything in the manuscript from the last twenty years is probably highly suspect.”

Overwhelmed by Mack’s bizarre treachery as well as the size of the archive, I told Susannah that I wanted to write the story of this flawed genius who set out to do—and then undo—so much. We agreed that she should be his literary executor, and she eventually found the perfect place for the archive—the Smithsonian, the official home of American history and the place where Mack had done so much work. The Smithsonian was happy to have the Monster, and archivists got to work organizing the 590 reels of tape and sorting the documents into 165 boxes.

John Troutman, a music scholar and a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, began putting together the manuscript for Biography of a Phantom. Troutman was impressed with Mack’s writing and research, but he found himself compelled to make a tough choice after reading Brother Robert, a 2020 book by Annye Anderson, another of Johnson’s sisters. Brother Robert is, by my count, the twelfth book about Johnson, and it’s one of the best, because after decades of stories of the musician as a dark blues lord, Brother Robert, which featured a new photo of him smiling on the cover, humanizes Johnson, showing the musician from the perspective of a young girl. He liked country music, she said, and rolled his own Bull Durham cigarettes. The book also villainizes Mack, who had misled the sisters, stolen photos from them, and held up for years the release of the Robert Johnson box set that finally earned money for some family members. “The biggest problem came from Mack McCormick,” wrote Anderson.

In his afterword, Troutman concludes that Mack’s bad behavior “delegitimizes” the agreement he had with the sisters, and he decided to excise anything in Biography of a Phantom that Mack had learned from them. The Smithsonian also decided to withhold from public view the photos of Johnson as well as notes from the interviews Mack conducted with the sisters, pending direction from the sisters’ heirs. Troutman was taking posthumous action against a con man—but also cutting out the book’s essence. “I think a lot of people are going to be disappointed,” Troutman told me. “I understand that.”

The Smithsonian archivists found a folder with an enemies list—and scripts full of Mack’s fantasies of what he would do to certain people he thought had betrayed him.

The Monster, though, still had more secrets to reveal—especially about Mack’s paranoia. The Smithsonian archivists found a folder with an enemies list—and scripts full of Mack’s fantasies of what he would do to certain people he thought had betrayed him. Guralnick and unnamed others were the intended recipients of copies of one unsent letter in which Mack wrote, “In my fading years should I go from town to town hiring bone-breakers to put you fellows in rehab for 2 years?”

The archivists also discovered that, as early as 1962, Mack was inserting dozens of “hoaxes” into the research notes that he shared with Paul Oliver for their unfinished book, The Blues Come to Texas—invented passages that would undermine the book if it were published without his permission. For example, Mack forged a death certificate for Blind Willie Johnson, showing, falsely, that the Texas-born guitarist was from the Cayman Islands. This wasn’t that big a surprise to me. Mack had told me in 2014 that he always “poisoned” his manuscripts. “I take things from Fitzgerald or Hemingway—take a paragraph and stick it in the manuscript so later I can remove it.”

When the long-shelved blues book was finally published by Texas A&M Press in 2019, the reception was rapturous. “The Blues Come to Texas is unbelievable,” said music scholar Elijah Wald. “People are going to be writing books based on Mack’s notes forever.” But researchers are going to have to be careful. Anyone reading the passage on the blues guitarist Smokey Hogg, for instance, will come across a passage based on an interview with an orderly at the Dallas veterans’ hospital named Dallas Blankenship, who says that Hogg committed suicide there in 1960 by throwing himself down an elevator shaft. According to Troutman, Mack sent the Blankenship interview transcript to Oliver in 1969 but wrote on his own copy, “NOTE THIS IS ALL HOAX, CAN BE DISCOUNTED BY TRUE COPY OF DEATH CERTIFICATE SHOWING NO SUICIDE.” In fact, Hogg died of a hemorrhaging ulcer. And Dallas Blankenship? That was the name of an administrative judge in Dallas County who attained fame in 1964 by appointing a replacement judge for the Jack Ruby trial.

As the editor of Biography of a Phantom, Troutman had a difficult line to walk. In some places he calls Mack out for his malfeasances; in other places he expresses some mild skepticism but lets the reader decide. He does that with Mack’s claim that he unplugged Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965—even though there’s no way that happened, says Wald, who wrote an entire book about the festival. And Troutman lets slide Mack’s claim that Virgie Mae Cain told him Johnson had said that his songs came to him “in a dream,” which I was suspicious of. I listened to the tape of two short

interviews Mack did with Cain in 1970, and she never says anything like that. Maybe she said this in another interview, but she seemed to have only a glancing familiarity with Johnson’s music; she remembered only one of his songs, the closest thing he had to a hit, “Terraplane Blues.” But it would be unfair to expect Troutman to vet every single fact; Mack’s disinformation is everywhere. Bruce Conforth and Gayle Wardlow’s esteemed 2019 Johnson biography, Up Jumped the Devil, for example, repeats Mack’s suspect claim that Johnson chauffeured the Oertles through Texas.

All these deceptions inevitably call into question other things Mack wrote. Was the old hobo Mack met in 1949 on a downtown Houston street actually Henry Thomas? Does it matter? Mack didn’t think so. “Henry Thomas had to have been pretty much like the man I met,” he told my former colleague Greg Curtis in Texas Monthly in 1977. “But I’m certain in my own mind it was Henry Thomas. It may not be the best scholarship to think so, but then scholarship isn’t everything, is it?”

In June the Smithsonian will open an exhibit on the Monster, featuring field notes, photos, concert posters, album artwork, and that old guitar from Mack’s living room. Then, later in the summer, Smithsonian Folkways will release a 66-song box set from the hundreds of hours of field recordings Mack made, mostly in Texas, plus a 128-page book of previously unseen photos with essays by various people, including Troutman and Susannah. The collection is an extraordinary cross section of music—barrelhouse piano, blues guitar, steel-guitar rags, zydeco tunes, and gospel songs—performed by well-known artists such as Hopkins and Lipscomb and obscure ones such as James Tisdom, a guitar-playing Black cowboy from Goliad, and George “Bongo Joe” Coleman, who played fifty-gallon oil drums on the streets of Galveston and San Antonio. This is what Texas once sounded like.

It might all be enough to remind us that, behind the shattered friendships, the brazen thefts, and the outright fabrications, Mack McCormick was a peculiar American hero: a searcher driven to go places no one else went, where he found, interviewed, and recorded guitarists, pianists, and singers who still stir us today. To Mack, scholarship wasn’t everything, not compared with curiosity, moxie, and old-fashioned hustle. Often more interested in telling a good story than in getting his facts straight, he perhaps had more in common with the artists he loved than with the journalists, historians, and academics with whom he now—finally—shares bookshelf space. If you love music, you have to feel some sort of unsettled affection for Mack and his beautiful, damaged mind.

“I see almost everything as a mystery,” he once told me. “You deal with the mystery, learn something about it, but you never solve the mystery. It’s never finished.” He was talking about his work and his travels, the connections he made and the music he heard. But he might as well have been talking about himself.

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Hellhounds on His Trail.” Subscribe today.