Late at night, after his kids have gone to bed, Ryan Bavetta sits down at the computer in his home office and goes to work again. By day, the former Google software engineer creates programs for NatureTeam, a firm he founded to help improve the habitats of neighborhood wildlife. But at night he works at something else, a project he keeps thinking he’s almost done with but just can’t quit. If you were to look over Bavetta’s shoulder in his cavernous woodshop-turned-office, you might think he was a detective, or a lawyer preparing to argue a case. He has dozens of tabs open in his browser, all pieces of digital evidence—pictures, YouTube videos, interview transcriptions, Reddit posts, maps—that he’s amassed over the past two years.

These late-night investigative sessions were supposed to be a temporary hobby. Starting in 2018, Bavetta joined thousands of other people trying to locate a bronze chest filled with gold nuggets, coins, jewelry, and other artifacts somewhere in the American West. Twice, after gathering evidence about the chest’s whereabouts from home, he flew to Salt Lake City and then drove to Yellowstone National Park to look for it. Each time he camped for a week. He drove rental cars on roads they couldn’t really handle. On the second trip, his wife Salomé joined him, and they bought an inner tube from a local adventure outfitter and used it to float down the Madison River in search of the treasure. Another day, they hiked off trail together and found themselves atop a hill washed with wildflowers, with a 360-degree view of West Yellowstone and a large bison marching directly toward them. These moments were exhilarating and beautiful, and Bavetta was looking forward to having more.

Then, on June 6, 2020, the incentive behind the thrilling trips to the mountains vanished. The chest was found. Still, for Bavetta and thousands of other hunters, the search wasn’t over. The chest’s location was never revealed, and the hunters began filing lawsuits and FOIA requests and analyzing photos and interviews to try to find out where it was. To this day, they’re still checking in with one another about new theories and developments that might bring them closer to understanding what the chest’s original owner had intended when he started this whole thing.

An ordinary treasure hunt would have ended when there was no more treasure, but “The Chase,” as the race to find the chest has been known since it began in 2010, was no ordinary hunt. It was, according to Alan King, Ph.D., a psychology professor at the University of North Dakota who studied it, the greatest treasure hunt in American history. It attracted a horde of competitive, devoted thinkers, sending them down a rabbit hole that turned out to have infinite proportions. And it’s not clear what it will take to get all of them out.

The treasure hunt that captured America’s heart is so famous that its particulars have been laid out in books, documentaries, and hundreds of articles: In 2010, an 80-year-old art dealer named Forrest Fenn hid a bronze chest full of loot—estimated to be worth at least a million dollars—somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. That same year, he published a memoir, The Thrill of the Chase, containing a six-stanza poem that would lead to its location. The key section suggested that the searcher “begin it where warm waters halt / And take it in the canyon down.” There was talk of cold, and a blaze, and the cryptic “The home of Brown.”

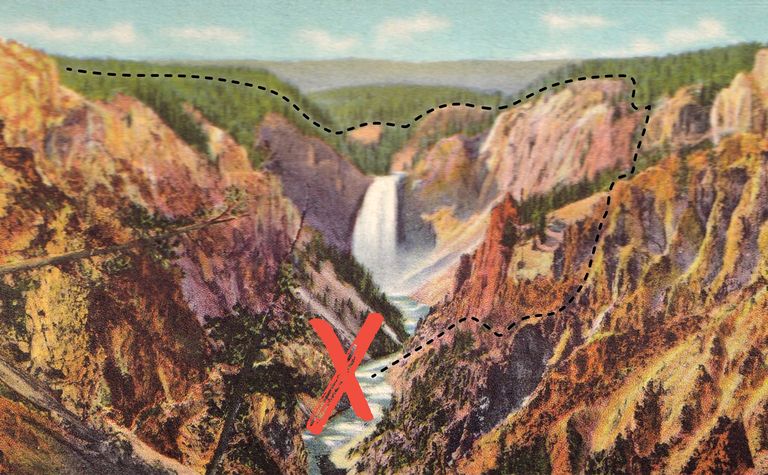

The poem was vague enough that each clue could apply to hundreds of places, depending on how creatively one thought. Many seekers interpreted the first clue, “where warm waters halt,” to mean a place with geothermal activity, which led them to various locations in Yellowstone—a place that also had great sentimental value to Fenn. From home, they pored over maps and did their best to apply the next eight clues to whatever starting point they’d picked. Often they’d be confident about six or seven clues in total, and would arrive at a final destination that only worked by shoehorning a meaning onto the last clue.

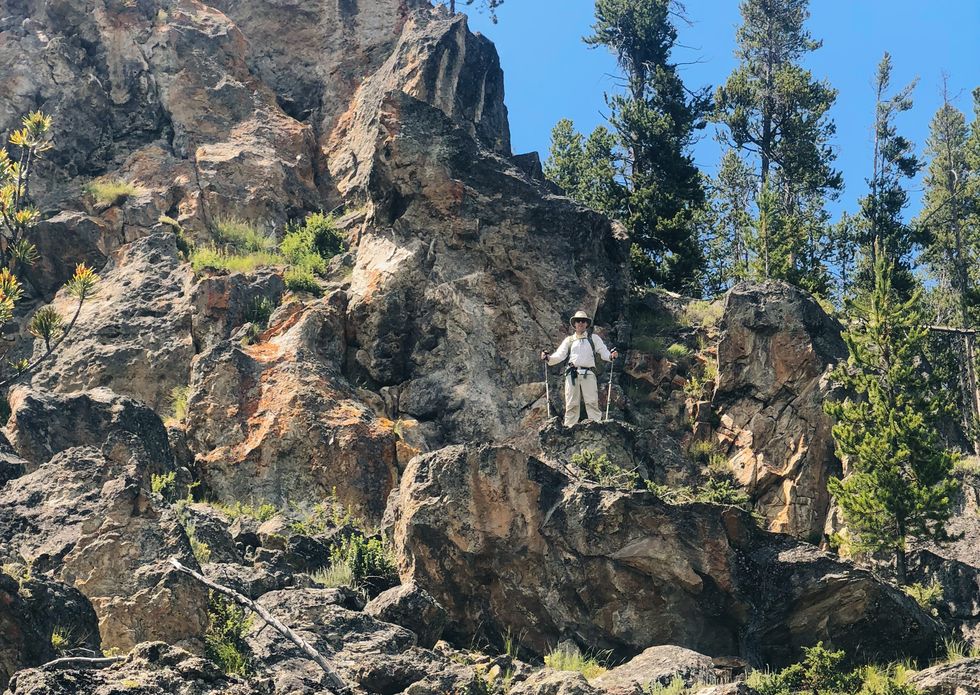

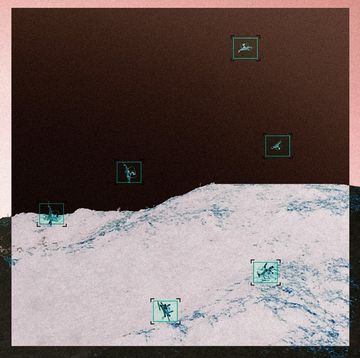

After deciding they knew where to look—and hunters universally reported feeling incredible confidence in these decisions—people would set out to scour that area in real life. Some seekers took weekends to confirm their hunches in the wilderness; others spent weeks or months in the West. They traversed snowy mountains, waded in freezing waters, trespassed on private land, and in some cases needed assistance from search and rescue teams to get out safely. Multiple people have admitted hiking over unmarked terrain for more than 10 or 15 miles in a single day during these searches, farther than they had ever walked in their lives before.

King, the North Dakota psychology professor, joined the Chase in 2015 after seeing Fenn on an episode of CBS This Morning; he later published an academic paper called “Treasure Hunting as an American Subculture: The Thrill of the Chase,” and estimates that the search group eventually numbered more than 400,000 people. They were drawn by the deceptive simplicity of Fenn’s poem, as well as the outdoor adventure the hunt required. But the breadth of knowledge that they had to draw on to find the solution—searching for clues in geography, history, literature, military lingo, aviation, archaeology, art, even business—had kept many of them searching. “The chest had value, but that’s not what drove us. It was the intellectual challenge,” King says. “For those of us who got into it, it truly was thrilling on a day-to-day basis.”

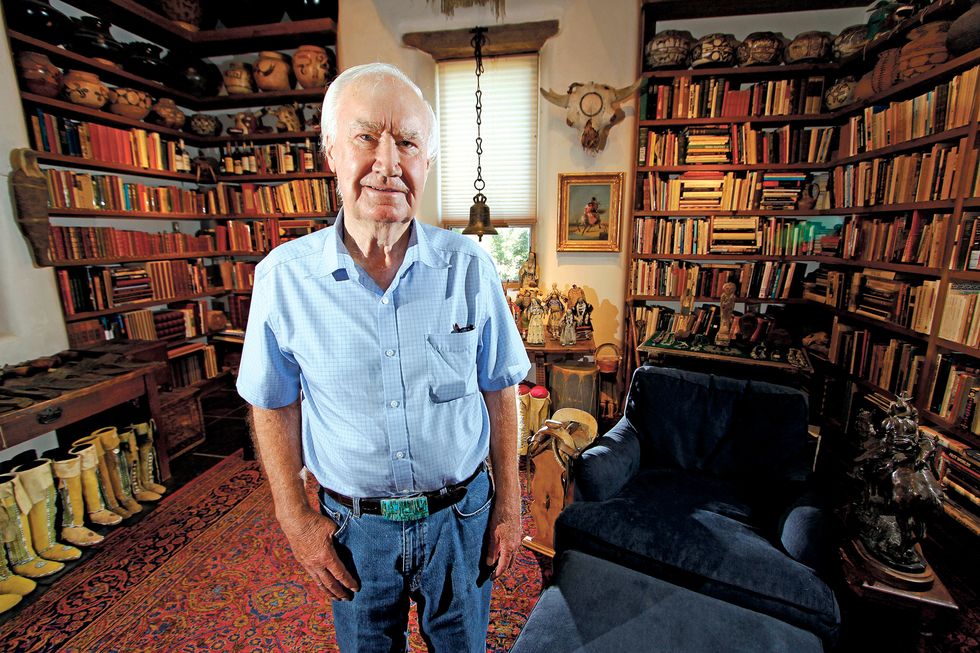

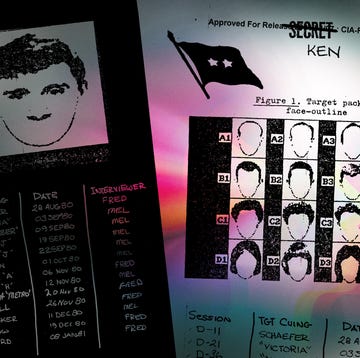

Much of the draw was Fenn himself. Born in Texas in 1930, he spent summers fishing with his father in Yellowstone and developed a love of the outdoors. He joined the U.S. Air Force at age 20 and flew hundreds of combat missions during the Vietnam War. He loved pirate stories, and alongside his own round-the-world antiquity-collecting exploits, he had a swashbuckling air even after he settled down in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There he owned an art gallery and a house filled with a uniquely astounding collection of artifacts. That collection, said to include a mummified falcon from King Tut’s tomb and Sitting Bull’s peace pipe, likely included looted objects. It aroused enough suspicion to trigger a major FBI raid in 2009, but Fenn was never charged with a crime.

People called Fenn “a hustler,” “a rascal,” the “trickster coyote” from Native American folklore. He first dreamed up his treasure hunt after being diagnosed with kidney cancer, intending to die alongside the chest at a special spot in the woods so that whoever found it would be robbing his grave. When he recovered and decided to hide the chest anyway, his slippery, roguish life became a part of the quest. “You figure him out, you’ll figure this poem out,” says Michael Mull, an U.S. Army veteran in Oklahoma who says his eight-year quest for the treasure ended up being a spiritual experience.

But Fenn did not make this task easy. While the hunt was ongoing, he published two more memoirs and hundreds of digital scrapbooks and blog posts. He spoke to the press and nurtured relationships with seekers, in person and by phone and email. For a while, he revealed cryptic half-clues on his website every Friday. “[Fenn] was the Riddler,” King says. “Every question was answered with a riddle, and we all hung on his every word.”

So what happens when a community of compulsive puzzle solvers encounters an unreliable narrator whose goal might be to achieve notoriety and not much else? Things get intense. At least one searcher tried to derive geographic coordinates from the poem using homophones (with every instance of “too” being the number two, and so on). Anthony Michael, who laid out his solution to the poem in a book called The Solve: Finding Forrest Fenn’s Fortune and Leaking the Lie That Endangered His Legacy, determined that the poem’s clues made the shape of an omega symbol when drawn on a map. (Fenn’s first memoir ends with a double omega imprint.) Justin Posey, a passionate searcher whose quest was documented in a New York magazine feature in 2020, developed software to analyze all of Fenn’s recorded interviews for emotions that suggested he was dancing around a hint about the chest’s location. He also trained his dog, Tucker, to sniff out buried bronze.

Some searchers began stalking, threatening, and attempting to blackmail Fenn and his family. In 2018 a man broke into his house; Fenn’s daughter held the man at gunpoint until police arrived. Five searchers died in accidents during their trips to locate the treasure: Randy Bilyeu, age 54, disappeared after taking a raft to search the New Mexico backcountry. Paris Wallace, 52, was found not far from where he’d tied a rope around a rock on a tributary of the Rio Grande. Jeff Murphy, 53, fell 500 feet after accidentally walking into a chute, and Eric Ashby, 31, fell off a raft in the Arkansas River and didn’t resurface. In 2020, a few months before the treasure was found, Michael Sexson, 53, died after getting stranded on a snowmobile without sufficient winter clothing. At one point, law enforcement officials in New Mexico pressured Fenn to end the hunt to prevent more fatalities.

Wrangling with what he’d unleashed took a toll on Fenn. In 2019 he emailed Dal Neitzel, a prominent member of the Chase community, to say he was thinking of retrieving the treasure and calling off the hunt. Neitzel suggested that perhaps he should hide something less valuable in its place, like a time capsule, so that seekers would still be able to enjoy figuring out his special hiding spot. Neitzel seemed to be aware of a truth that Fenn did not: The Chase had taken on a life of its own. The chest was still the prize, but seekers were looking for something bigger. They craved an answer to a sprawling, fantastic puzzle, and they weren’t going to stop until they got it.

The MIT Mystery HUNT is widely regarded as one of the most complex events of its kind in the world. It pits teams of students against one another in a race to solve puzzles that lead to a hidden coin on the university’s campus. Teams can be as small as one person or comprise more than 100 people; when Ryan Bavetta participated, he was on a team of 30. Together, they tackled challenges that could include crosswords, logic problems, jigsaw puzzles, ciphers, and even tasks like baking and songwriting, which all eventually fit into what Bavetta calls a “meta meta puzzle,” which creates a narrative. Previous years have involved scenarios in which puzzlers are robbing fictional banks and trying to wake themselves up from an Inception-inspired dream. The winning team gets to design the next year’s hunt.

The thing about the MIT Mystery Hunts, Bavetta says, is that they end. “The solution is described, and everyone can have that moment of, Oh, that’s what was supposed to happen,” he says. It’s a moment of control and satisfaction that’s otherwise hard to come by in our increasingly uncertain world. The quest to find Fenn’s chest was like that. In some ways, it resembled the kinds of goals that drive people throughout a lifetime, says King, the psychologist. It wasn’t quite as important as finding a cure for cancer or landing men on the moon, but some of the factors involved were similar. It required commitment in the face of uncertainty and challenge.

Unfortunately, the Chase didn’t end like the MIT Mystery Hunt. In June 2020, Ryan Bavetta had just returned from a weeklong excursion to look for the chest in the mountains north of Santa Fe. This time he was exploring a theory that the chest was hidden near Cimarron Canyon, where there are signs for fly-fishing indicating warm waters with chili pepper imagery. Shortly after returning to California, Bavetta saw a Reddit post pointing to Fenn’s announcement that the chest had been found. In typical Fenn fashion, the alert was frustratingly cryptic: “THE TREASURE HAS BEEN FOUND. It was under a canopy of stars in the lush, forested vegetation of the Rocky Mountains and had not moved from the spot where I hid it more than 10 years ago. I do not know the person who found it, but the poem in my book led him to the precise spot… So the search is over.”

Bavetta was shocked. He’d expected the Chase to last for many more years, possibly beyond his lifetime. Now he realized he’d never spend another vacation searching for the treasure. In this year’s New Yorker documentary, searcher Justin Posey crumpled on camera when describing this moment. It was “crushing,” he said, like spending years training for a sport just to have it canceled forever while you’re on your way to the Olympics.

At least the mystery has been solved, Bavetta thought at the time. He and the rest of the search community began to eagerly anticipate the release of the answer to the poem. But official information came out in a trickle, and as the months went by, impatience mounted. The Chase community started posting their complete guesses online. They worked together to derive clues from the single photo that Fenn released of the chest in situ in its unnamed hiding place. They analyzed how dry the ground looked, what kind of grass and pine needles were present.

The wait was interminable, painful. “People were emailing Forrest and getting responses saying that everything will come out eventually,” Bavetta says. Fenn told the community not to pay out any bets they had made on where the treasure was. He said nothing was as it seemed. “He said provocative things that have kept some people in a conspiracy mindset.”

And then, without ever revealing his hiding place, Fenn died, which was exactly the kind of thing a trickster coyote would do. The finder, a 32-year-old medical student named Jack Stuef, finally came forward in December 2020, in response to a lawsuit filed by Chicago attorney Barbara Andersen claiming that the finder must have hacked her computer and stolen her solution to the poem. In a post on Medium, he said he would have preferred to remain anonymous, but that the lawsuit would make his name a matter of public record. Then he dealt the search community possibly the hardest blow possible: “I have never revealed where I searched for and found the chest to any person other than [those] whose job requires them to know that information and keep it confidential,” he wrote. “And I never plan to do so.”

When Bavetta began trying to solve Fenn’s poem in earnest, in 2018, he did so thinking that there must be something simple all the other seekers had been missing for the past eight years. Obviously, he thought, focusing all your time on the problem didn’t work, because people had done that, and no one had found the chest. Some of the most fervent searchers had devoted years of their lives to the effort. Justin Posey, the hunter featured in the New York magazine story, spent entire summers in the Rockies. Cynthia Meachum, a searcher who is well known to the Chase community for her intense commitment to the hunt and the friendship she forged with Fenn, began looking for the treasure full time after being laid off from her job as a field service engineer in 2015, and spent more than $10,000 on the quest in one year alone.

Bavetta had never wanted to go all in on treasure hunting. In between his 2018 trips to Yellowstone National Park and his 2020 trip to Santa Fe, he says, he mostly ignored the Chase. It was merely an entertaining pursuit that he could pick up and put down whenever he felt like it. But after the chest was found, something changed. As time went on and no one revealed the solution, he began to obsess over where Fenn might have hidden his treasure. He started going to his home office in the evenings; his search started consuming a larger part of his life.

On Reddit, a person had uncovered Stuef’s username, so Bavetta retrieved Stuef’s deleted posts, including those about his searches and emails he’d exchanged with Fenn. On September 8, 2022, Bavetta submitted the first of three FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) requests to the federal government, looking for email correspondence between officials at Yellowstone National Park. A few weeks later, he received what he was looking for: heavily redacted emails that included maps of a spot in the park called Nine Mile Hole and discussion of a “potential area of disturbance.” Bavetta pasted these emails into a Google doc full of digital evidence.

Eventually he created a 58-page timeline recreating Stuef’s search. He isn’t above a little light conspiracy theorizing: He believes, for example, that some of Stuef’s emails from 2019, about establishing residency in Puerto Rico for tax reasons, indicate that he didn’t find the chest when he says he did, in the summer of 2020.

In fact, the community of remaining seekers has spent so many years overthinking everything about Fenn and his treasure that few of them are able to take Stuef’s story—that he found the chest honestly, by solving the poem himself—at face value. Some think Stuef never solved the poem, but discovered the place Fenn wanted to die and found the chest there by a combination of luck and other means, perhaps dishonest ones. Others believe Fenn helped Stuef find the location because he wanted the Chase to be over before he died. At least one person, who spoke to Popular Mechanics on condition of anonymity, has decided that the whole Stuef story is an elaborate ruse and the treasure is still out in the woods somewhere. “I am still looking. I know this sounds like I am delusional,” he says.

Bavetta has become confident that Stuef found the chest near Nine Mile Hole, a fishing area on the Madison River near Yellowstone’s west entrance. He even made a histogram of data he got from the redacted FOIA emails between National Park Service officials showing that the officials discussed Nine Mile Hole and the Fenn treasure separately on the same dates. While he doesn’t have any plans to visit there himself, Nine Mile Hole has become a popular guess of the chest’s location, and many other searchers have gone there looking for it. According to Bavetta, who has kept track of others’ trips via Reddit and a Discord channel where the community continues to share information, no one has found anything resembling a blaze—the final clue—at this location. But in one of his few statements to the Chase community, Stuef said he had found the blaze “damaged.” It may not be recognizable at all anymore.

In July 2021, Cynthia Meachum traveled to Nine Mile Hole armed with a picture of a tree that Stuef had posted on Reddit at some point. She found the tree, and in a YouTube video recapping this excursion, says she knew she was “walking in Jack’s footsteps.” Meachum intends to keep searching until she can pinpoint the exact spot where the chest was hidden. “I want to know what his special place was and I want to be able to go there and I want to sit there,” she says in the New Yorker documentary. “That would be the ending. To know that.”

Fenn will never be able to tell Meachum if she’s found the spot or not. And she’s unlikely to receive confirmation from Stuef. Absent any other information, Meachum and the rest of the community will have to make their own decisions about where they think the chest was.

But there may be some relief yet: One recent lawsuit against Stuef and the Fenn estate, dismissed by a judge but working its way through appeals, could force the few Yellowstone National Park rangers who know where the chest was to state it publicly. And then there is the treasure itself: Stuef sold the chest and its contents in a private transaction this September. The new owner put those contents up for auction online on November 11. The items include a glass jar rumored to include Fenn’s unpublished autobiography.

“The biggest question is: What does it say?” Bavetta asks. There is some chance that in the autobiography, Fenn described either the hiding of the chest or the location where he wanted to die. He may have described writing the poem, or may even solve it. This would satisfy Bavetta: Now that he believes he knows the rough location, the exact spot and its relation to the clues in the poem would be enough to set his mind at ease.

Even with its fizzled ending, Fenn’s puzzle changed people’s lives. Jason Hamon, a 34-year-old Texan, has formed a Dungeons and Dragons group with the friends who used to help him search potential treasure coordinates. Steve Brady, a 56-year-old in Idaho who worked on solving the poem with his elderly father, is now researching the history of Yellowstone, saying the park itself was a grand treasure he discovered. Justin Posey, the searcher from the New York magazine story and the New Yorker documentary, said he was thinking of starting his own treasure hunt, for a bunch of potentially valuable meteorites he found while looking for Fenn’s box.

Bavetta says he would be happy in two circumstances: “If the person who receives [the autobiography] opens it and either reads out loud the contents or summarizes what it says. Or if it was thrown out to sea and sinks to the bottom of the ocean.”

For now, he’s still looking for what comes next. Recently he met up with another Reddit user who had a permit to dig in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. They were looking for one of 12 ceramic boxes that writer Byron Preiss claimed to have hidden in parks across the U.S. and possibly Canada back in 1982. With a park ranger chaperoning, they dug a two-foot by two-foot hole. They found nothing.