Profile in courage: When Jimmy Carter helped save a nuclear reactor

Loading...

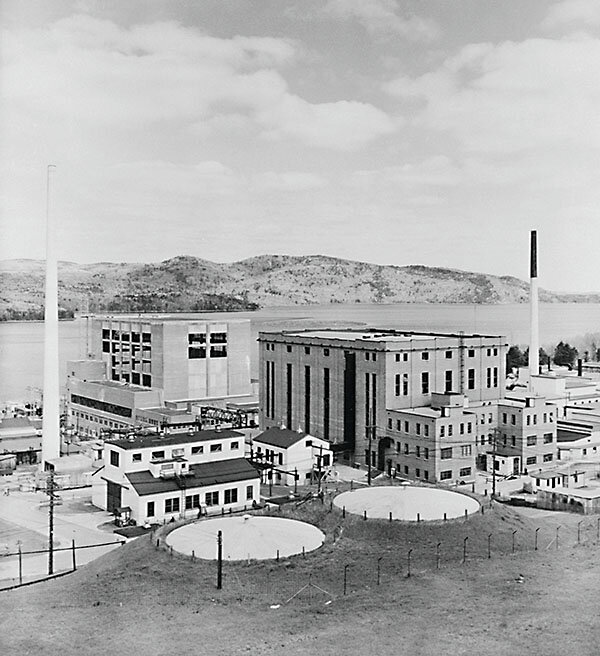

| DEEP RIVER, ONTARIO

In 1952, the U.S. military needed leaders for a new kind of mission. It involved a treacherous journey into unexplored territory, with danger a certainty.

But 28-year-old Navy Lt. James Earl Carter Jr. answered the call.

Why We Wrote This

With the former president having entered hospice, a little-known chapter from Jimmy Carter’s naval career illustrates his courage and problem-solving skills under hazardous conditions.

“Unexplored territory,” in this case, was the aftermath of one of the world’s first serious nuclear accidents. On Dec. 12, 1962, the NRX research reactor at Chalk River, Ontario, in Canada had suffered a partial meltdown. Ruptured radioactive fuel rods were stuck inside the reactor core. Radioactive water filled the reactor building’s basement.

Lieutenant Carter was an officer in the Navy’s nuclear submarine program and an expert on reactors and nuclear physics. He led a 23-person Navy crew charged with helping in the Chalk River cleanup. They were told that due to exposure to radioactivity, it was possible they would never have children.

He brought to the task precision, intelligence, and dedication – qualities that would later make him, if not a great president, perhaps the most consequential ex-president in U.S. history.

“He did an outstanding job,” said nuclear sub pioneer Adm. Hyman Rickover at the 1977 commissioning of a nuclear-powered cruiser.

In 1952, the United States military needed leaders for a new kind of mission. It involved a treacherous journey into unexplored territory, with danger a certainty.

But 28-year-old Navy Lt. James Earl Carter Jr. answered the call.

“Unexplored territory,” in this case, was the aftermath of one of the world’s first serious nuclear accidents. On Dec. 12, 1962, the NRX research reactor at Chalk River, Ontario, in Canada had suffered a partial meltdown. Ruptured radioactive fuel rods were stuck inside the reactor core. Radioactive water filled the reactor building’s basement.

Why We Wrote This

With the former president having entered hospice, a little-known chapter from Jimmy Carter’s naval career illustrates his courage and problem-solving skills under hazardous conditions.

Lieutenant Carter was an officer in the Navy’s nuclear submarine program and thus an expert on reactors and nuclear physics. He led a 23-person Navy crew charged with helping in the Chalk River cleanup. They were told that due to exposure to radioactivity, it was possible they would never have children.

He brought to the task precision, intelligence, and dedication – qualities that would later make him, if not a great president, perhaps the most consequential ex-president in American history. His famously demanding Navy boss, nuclear sub pioneer Adm. Hyman G. Rickover, later praised the work Lieutenant Carter did and said it laid the ground for his larger understanding of atomic science.

“He did an outstanding job,” said Admiral Rickover at the 1977 commissioning of a nuclear-powered cruiser. “In the process, he learned much about the practical aspects of nuclear power.”

The area where the Chalk River accident took place is in remote northern Ontario, 120 miles north of Ottawa. The site was chosen during World War II because of its access to cooling water from the Ottawa River and the stability of the region’s granite rock base.

Officials also felt the isolation of the place meant that spies would stand out immediately.

Following the war, it continued as an important nuclear research facility. Great minds of physics, such as Enrico Fermi, came to visit. The first highly enriched uranium used to power U.S. nuclear subs came from Chalk River.

Then on Dec. 12, 1952, two human errors in quick succession led to an uncontrolled chain reaction, which caused cooling water to boil, fracturing the control rods and causing an explosion. A quick release of more water flooded the building and prevented a full meltdown.

But 66 pounds of radioactive gas had already escaped from reactor building chimneys. Radiation alarms in town rang for 16 hours. Fortunately, no one died as a result of the accident.

At the time, the future 39th president of the United States was living in Schenectady, New York, and working at a submarine research facility. After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1946, he had applied to the new nuclear-powered submarine program, been interviewed by then-Captain Rickover, and been accepted.

He was in line to be a top officer on the Navy’s second nuclear sub, the USS Seawolf, and was designing a training program for enlisted members of the new nuclear effort. For Captain Rickover, Lieutenant Carter was a logical choice to send to Chalk River to help the Canadians clean up after their accident.

The rising young officer would gain valuable firsthand experience. At the same time, he could help the reactor get back online – something important to the U.S., as Chalk River was a source of fuel for its burgeoning nuclear Navy.

A dangerous mission

So, Lieutenant Carter led a team of 22 other U.S. servicemen to the remote Ontario outpost. Their role was to dismantle some parts of the reactor.

Each man could only stay in the reactor for a very brief period of time. They had particular nuts and bolts they were assigned to remove. An exact model of the NRX was constructed on a tennis court adjacent to the reactor building, and under Lieutenant Carter’s supervision the team members rehearsed over and over until they were economical in their movements and understood their task precisely.

They were then lowered onto the reactor dome for 90 seconds at a time, gradually removing the layers of shielding to allow access to the reactor core.

“Each time our men managed to remove a bolt or fitting from the core, the equivalent piece was removed on the mock-up,” writes Mr. Carter in his presidential campaign biography, “Why Not the Best?”

Lieutenant Carter and his team received perhaps 1,000 times the dose of radiation now allowable. They wore red undergarments with white cotton boiler suits and steel-tipped boots with orange-painted toe tips – clothes that were distinctive so they couldn’t be worn outside the area and possibly spread contamination.

“For about six months after that, I had radioactivity in my urine,” Mr. Carter told Canadian journalist Arthur Milnes in 2011.

Three Mile Island

Due to the heroic efforts of hundreds of workers, including the U.S. Navy contingent, the NRX reactor was restarted only 14 months after its accident.

Despite the dire predictions, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter went on to have children.

But he never served as a top officer on the USS Seawolf. Mr. Carter left the U.S. Navy in 1953, after his father died, to take over the family farm. Eventually he turned his ambitions to politics, rising to governor of Georgia and then president of the United States.

Still, Mr. Carter’s experience with nuclear reactors in the Navy and at Chalk River may well have informed his management of the Three Mile Island reactor accident in Pennsylvania in 1979 – a partial meltdown that remains the worst nuclear incident in the U.S.

After the accident, he publicly expressed confidence that the situation was under control. Behind the scenes he received regular updates from the then-chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Harold Denton.

President Carter would ask detailed and technical questions during these briefings. At one point, no one seemed to have answers for the U.S. chief executive.

“Do you think there is anyone there [at Three Mile Island] who knows what’s going on?” he said, dryly, according to a later account in The Washington Post.