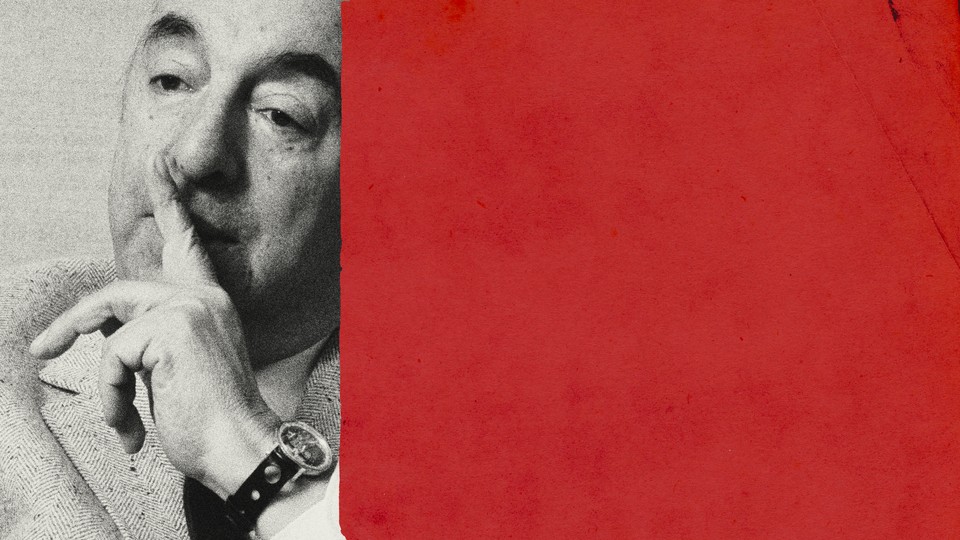

Who Poisoned Pablo Neruda?

A new report suggests what some have long suspected: One of the world’s most famous poets may have been murdered.

Repressive regimes tend to be unimaginative. They persecute and censor their opponents, herd them into concentration camps, torture and execute them in ways that rarely vary from country to country, era to era. As the outrages pile up, public opinion becomes exhausted.

Once in a while, however, a story surfaces that is so startling, so malicious, so unheard of, that people are jolted out of their fatigue.

Recent news about the mysterious 1973 death of Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel Prize winner and one of the greatest poets of the 20th century, has created such an occasion. According to Neruda’s family, a new forensics report conducted by a group of international experts has concluded that he was poisoned while already gravely ill—a victim, most probably, of the Chilean military he had politically opposed. Even the most jaded onlookers should feel disturbed enough to pay attention—not just for what this development reveals if it is in fact true, but for how it might shape the legacy of one of history’s most complicated and most talented poets. Neruda’s own reputation is already blemished, his considerable moral failings as a person having overshadowed the once-universal acclaim for his art.

For many years, I believed that Neruda had died of prostate cancer in a Santiago hospital on September 23, 1973, 12 days after the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende. Neruda’s widow, Matilde Urrutia, had told me that this was the cause of his death, even though she’d emphasized that the destruction of democracy and of the peaceful revolution her husband had so enthusiastically embraced had hastened his passing.

Even then there were rumors that he had been killed by an agent of General Augusto Pinochet’s secret police, but I dismissed them over the years as unfounded, because, I asked myself, why would the military go to the trouble of assassinating someone who was already dying? Why risk something that scandalous being discovered and further soiling their already foul international image?

In retrospect I wonder if perhaps I was so tired of tales of torture and disappearances, so full of death and grief, that I could not deal with one more affront. I preferred to shield the sacred figure of Neruda from the violence. This became even truer when Chilean democracy was restored in 1990 and my fellow citizens had to retrieve from sand dunes and caverns and pits so many remnants of men and women who really had been slaughtered by the state. Why not let Neruda, at least, rest in peace?

I began to change my views in 2011, when Manuel Araya, Neruda’s chauffeur, announced that he was sure the poet had been poisoned, that the cause of death was a substance injected into his abdomen. The Communist Party to which Neruda had belonged demanded an inquiry, which led to the exhumation of his body two years later. A first examination certified that Neruda had died of cancer, but a second panel of experts in 2017 rejected cancer as the cause of death and determined that his demise was probably because of a bacterial infection, without establishing whether its source was endogenous (having originated from within his body) or exogenous (introduced into his body externally, by someone or something else).

And now, six years later—oh how slowly the wheels of justice move—Neruda’s nephew says he has seen the report of a panel of experts from Canada, Denmark, and Chile who have concluded that Neruda’s death can be attributed to Clostridium botulinum—the same toxin that causes botulism—that may have indeed been injected into his body. Yesterday, the report was sent to a judge who will have to rule officially on the findings and, presumably, stipulate what measures should be taken to ferret out the alleged culprits, though it is doubtful that anyone will ever be put on trial.

If the shameful half century that has passed since his death seems to guarantee the impunity of those who may have ordered his execution and carried it out, the discovery surfacing precisely in 2023 alters the previously accepted history of both Neruda and the country he loved in ways that are significant and unique.

For starters, as the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup approaches, the apparent manner of the poet’s death suggests once again what Pinochet and his civilian accomplices were capable of, reminding Chileans and so many others around the world of the atrocities of a perverse dictatorship, making it more difficult, as conservatives in Chile would like, to whitewash the past and erase their own sins. As for Neruda himself, the reports of assassination come at a peculiar moment of his afterlife following a series of terrible disclosures.

In the early 1930s, Neruda married a Dutch woman, Maryka Antonieta Hagenaar, who gave birth in 1934 in Madrid to a daughter, Malva Marina. But the little girl was born with hydrocephalus, an inflammation of the brain that causes the head to swell disproportionately—a deformity that Neruda was clearly unable to endure, especially after he fell in love with another woman. He abandoned his family, and Malva died at the age of 8 in Nazi-occupied Holland. Neruda reportedly did not send funds to Hagenaar or ever visit his child’s grave. Added to this revolting conduct was Neruda’s own admission in his posthumously published memoir, I Confess I Have Lived, that he had raped a servant girl in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) many decades ago. This man, known for his defense and compassion for the victims of the world, had himself been a predator.

The fact that Neruda now becomes one more in an array of martyred revolutionaries who died fighting for the freedom of Latin America does not make his personal transgressions any less disgusting or disheartening. But the notion that he was murdered may, one would hope, ultimately inspire readers to rediscover how his poems still speak to us today.

Younger generations in Chile have had their back turned on Neruda for a number of years, and not just because of what is now known about his personal life. They have favored instead the feminism and tender severity of his fellow Nobel laureate Gabriela Mistral or the sardonic, corrosive anti-poems of Nicanor Parra. When I ask young people about Neruda, they almost unanimously declare that his solemn, grandiose style and torrent of interminable metaphors do not sit well with these fractured, uncertain times, with their own drifting, deracinated lives.

And yet, Neruda’s verses continue to have extraordinary relevance. Most obviously, they could teach readers in our current anxious and disembodied epoch to celebrate love and sex, and to battle the persistent loneliness that afflicts young and old today. But Neruda matters also because he sang into sensuous existence the most modest and ordinary objects of life—tomatoes, artichokes, socks, bread, air, copper, fruit, onions, a clock ticking in the middle of the night, the foaming waves of the sea, the everyday things and moods like tranquility and sadness that, after the poet has illuminated them, we can no longer take for granted. And for those who want to make sense of modernity and its discontents, there are the hypnotic poems of Residencia en la Tierra, which explored the dreams and nightmares of our hallucinatory era in ways that rival the work of any other author, dead or alive.

But there is more. This year Chile is planning to establish for itself a new constitution. Neruda can rouse his fellow countrymen and women to ask themselves about their deepest, tumultuous identities. At a time, for instance, when the question of the planet’s durability is paramount, a supremely ecological Neruda spurs us to care for nature; teaches us to venerate the stones of Latin America, its sands, raw materials, unbridled vegetation and serene grains; proclaims that the mountains and fields are demanding a society as generous as the land itself; brings back to life the Indigenous vision that insists that a different relationship with the Earth is possible. He was the author who, in his Canto General, prophetically reimagined our whole Latin American continent, plunged into its minerals, peeled back the hidden layers of its virulent history of betrayals and insurrections, giving a voice to the humble, trampled, rebellious workers of the past and offering words of encouragement to the rebels of the future.

The question of whether one can love the art while deploring the artist is not unique to Neruda, and it’s a dilemma being confronted not by just the young. Neruda’s moral failings are real, and this news of how he seems to have died might not change the revulsion that many feel and that has tainted his poetry for them. But it is also possible that the knowledge that he was most likely assassinated might inspire some readers to revisit him, recognize his imperfections, and still come to appreciate those stanzas of his that allow us to become more human.

Listen to him: “Here are my lost hands. / They are invisible, but you / can see through the night, through the invisible wind. / Give me your hands, I see them / over the harsh sands / of our American night, / and choose yours and yours, / that hand and that other hand / that rises to fight / and will again be made into seed. / I do not feel alone in the night / in the darkness of earth /… From death we are reborn.”

It would be ironic and somehow fitting if the death that his enemies willed upon Neruda leads readers back, 50 years later, to verses that tell us that poverty can be vanquished, that injustice is not eternal, that oppression can be resisted, that the dead can be rescued from silence.

The Suicide Museum, investigates the death of Salvador Allende.