Flying squirrels secretly glow pink, thanks to fluorescence

Drab by day, North America’s three species of flying squirrels are all fluorescent. But why?

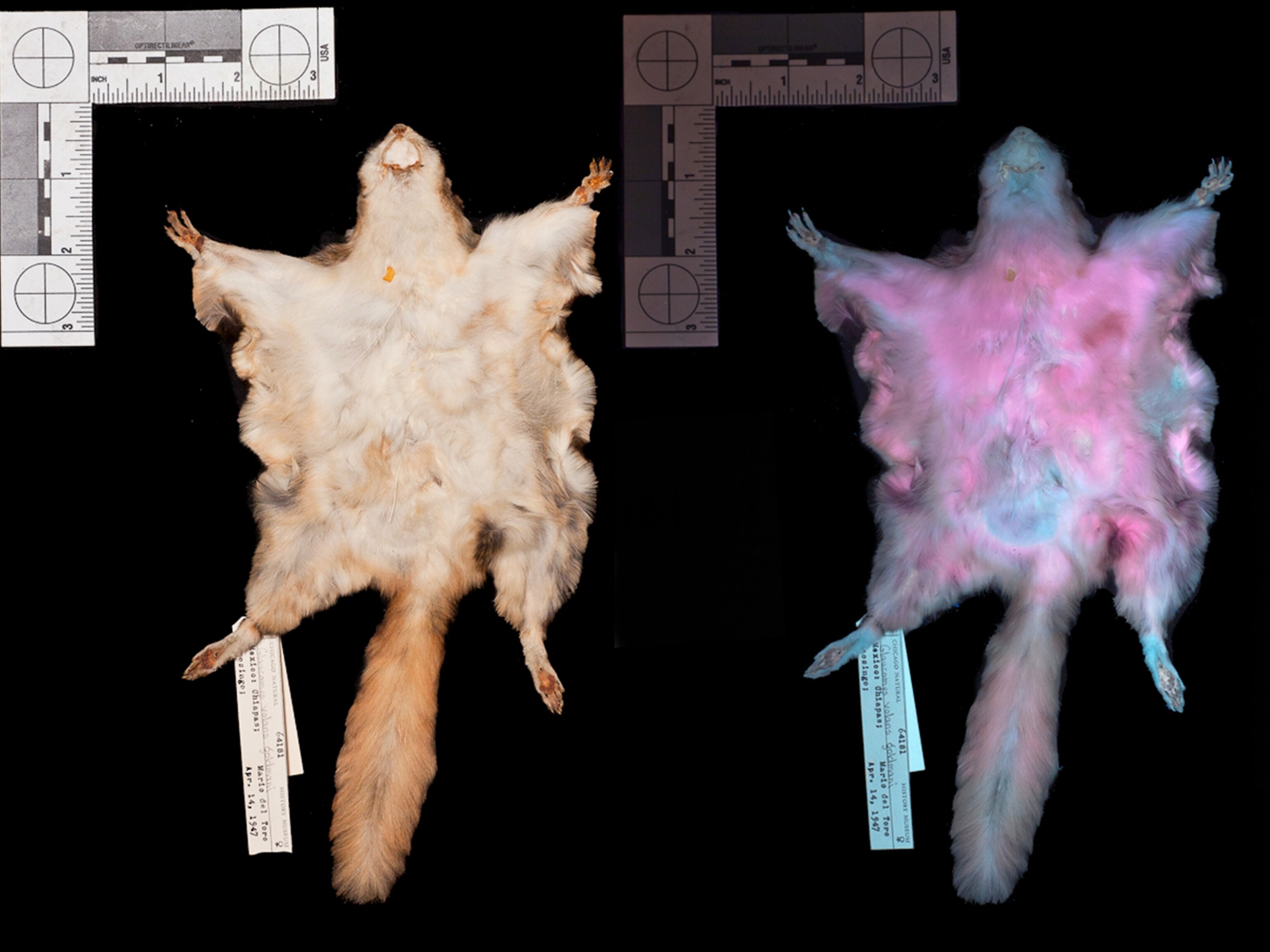

Flying squirrels were already exceptional, as far as rodents go. Gifted with a flap of skin between their limbs, they can glide long distances between the trees where they live. But new research suggests some of the critters hide a bizarre secret—their fur glows a brilliant, bubble-gum pink under ultraviolet light.

This makes these squirrels one of only a few mammals known to fluoresce, which is the ability to absorb light in one color, or wavelength, and emit it in another. The finding raises tantalizing questions about the function of this glowing ability and suggests that the trait may be more common than previously thought among mammals.

The discovery happened entirely by accident, says Paula Spaeth Anich, a biologist at Northland College and senior author on the new study, published this month in the Journal of Mammalogy.

Anich says that Jon Martin—a forestry professor and coauthor on the paper—was exploring a Wisconsin forest at night, using a UV flashlight to scan the canopy for lichens, fungi, plants, and frogs that occasionally fluoresce.

“One evening,” says Anich, “he heard the chirp of a flying squirrel at a bird feeder, pointed the flashlight at it, and was amazed to see pink fluorescence.”

Squirrels aglow

Martin told Anich—who studies rodents—about the encounter. “I have to admit that the discovery was a little confusing to me,” says Anich. “I tried to put it into some context I could understand. Was this due to diet? Was this a local phenomenon?”

To see how widespread the trait might be, the researchers took to the Science Museum of Minnesota and the Field Museum in Chicago to examine the skins of flying squirrels. North America’s flying squirrels (Glaucomys) consist of three forest-dwelling species, ranging from the Northwest through Canada and the eastern United States down to Central America. The team took photographs under visible and ultraviolet light, compared them to non-gliding squirrels, and measured the intensity of fluorescence.

While non-flying squirrels didn’t glow, all but one specimen of the gliders did fluoresce a similar pink color. This was true despite the sex or location of the animal.

“The fluorescence was there in the Glaucomys from the 19th to 21st century, from Guatemala to Canada, in males and females, and in specimens collected in all seasons,” says Anich.

While other animals fluoresce—puffins’ bills and chameleon’s bones give off an eerie, blue glow under UV light, for example—the only other mammals known to have fluorescent fur are about two dozen species of opossum. These marsupials, scattered across the Americas, aren’t closely related to flying squirrels, live in different ecosystems, and have a different diet.

But flying squirrels do share one thing with the opossums: they’re all active at night and twilight, where other squirrels are mostly diurnal.

Low-light conditions are relatively rich in ultraviolet light, and UV vision is generally thought to be important to nocturnal animals. Because of this, Anich thinks the pink glow has something to do with night-time perception and communication.

The pink color may also help flying squirrels navigate cold, snowy environments, which all three species encounter in parts or all of their range.

“The trait might be more visible, or noticeable, in snowy conditions because of the high rate of UV reflectance off of snow,” says Anich. “If this trait is involved in animal communication, snow might give it a ‘boost.’”

Signal, noise

But what might the fluorescence be saying? Corinne Diggins—a wildlife biologist at Virginia Tech University not involved in this study—wonders if it’s a way for the squirrels to signal relative health and vivaciousness to potential mates.

“Maybe a brightly pink fluorescent belly on a male flying squirrel makes a female swoon,” Diggins says.

However, Anich doesn’t think that’s as likely, since there was no seasonal peak in fluorescence or difference between males and females. Meanwhile, the mechanism that causes fur to fluoresce is unknown.

Anich and her team offer other possible uses for the pink glow: camouflage or mimicry. Many lichens that blanket trees also fluoresce, and the squirrels’ pink fur may be a way to blend in to their surroundings. Alternatively, some owls fluoresce bright pink on their undersides, so the squirrels may be mimicking this coloration.

Jim Kenagy, curator of mammals at University of Washington’s Burke Museum and not involved in this study, is curious to see if the fluorescence is found in flying squirrel species elsewhere in the world.

“It’s surprising that they did not test more of the species that represent the rest of the flying squirrel subfamily,” says Kenagy.

The discovery, more than anything, reveals how much we don’t know.

“[This research] highlights how much more there is to learn about how flying squirrels interact with each other and their environment,” says Diggins.

Understanding how flying squirrels see their world—and how that world sees them—is crucial for fully appreciating their habitat needs, which is deeply intertwined with their continued conservation. The discovery also presents the possibility that many other mammals have a UV-specific coat, completely unknown to us.

“The lesson is that, from our diurnal primate standpoint, we are overlooking many aspects of animal communication and perception that happen at twilight and night-time,” says Anich.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park