“Booksellers are constantly giving their patrons extraordinary bargains. In London recently a copy of an early edition of Keats’ Poems, originally bought from a dealer for 2s was sold for £140, and a first edition of Burns’ Poems bought in Edinburgh for 1s 6d brought £350.”

–R.M. Williamson, Bits from an Old Bookshop (John Menzies, Edinburgh, 1904)

*

Williamson may well have been in a position to afford the luxury of giving his patrons extraordinary bargains. Not all of us are. In part, what he says remains true, though; provided you sell a book for more than you’ve paid for it, what happens to it after that is largely in the hands of fate. Buying and selling books prior to the advent of the internet was a matter of judgement based on experience and a pile of old auction catalogues and records. Now—if anything out of the ordinary falls into my hands—I tend to go straight online to see what other people are selling it for and base my price on that.

When I discovered Williamson’s beautifully produced book in a box that I’d bought from a house in Edinburgh in the embers of last year, I couldn’t resist dipping into it straight away. My first instinct was that he was so generous about his customers, so passionate about his trade and so unfeasibly knowledgeable that he must have been a fictional creation, but last year a customer brought in a four-volume set of The Works of Robert Burns, calf-bound and published in 1823. Slipped between the endpapers of the first volume was a letter, in the original envelope, stamped and dated Saturday 9 February 1929.

It was a handwritten response to an M. Maclean Esq., and in beautiful cursive handwriting it explained that “In reply to you, I can’t think that your friend’s edition of Burns is of high value. If, however, he is in any doubt he should write to Maggs Bros, Booksellers, London. Yours, R. M. Williamson.” Williamson’s astonishment that a Kilmarnock edition of Burns could have made £350 in the early twentieth century would doubtless have been surpassed had he known that a copy sold for £40,000 in 2012 through the Edinburgh saleroom Lyon & Turnbull.

Williamson’s business no longer exists, but Maggs—to whom he commended Mr Maclean for further advice—is still a distinguished force in the world of rare and antiquarian bookselling; in 1932 they pulled off the bookseller’s dream of buying (from the recently Soviet Russia) a Gutenberg Bible and a Codex Sinaiticus, or “Sinai Bible”—a handwritten copy of one of only four texts of a Christian Bible in ancient Greek, written in the fifth century.

Sixteen years prior, though, and among their most famous and unlikely acquisitions, was the purchase of Napoleon Bonaparte’s penis, which they bought in 1916 from a source with highly credible provenance: direct descendants of Francesco Antommarchi, who conducted the autopsy on Napoleon’s body. He had been bribed (it appears) by the emperor’s chaplain to remove the member in a posthumous act of revenge for Napoleon’s repeated mockery of his chaplain for impotence. I’m not entirely sure that it’s possible to emasculate a corpse.

Maggs sold the dismembered member to an American antiquarian bookseller in 1924 for £400. According to that most reliable of sources, Wikipedia: “A documentary that aired on Channel 4, Dead Famous DNA, described it as ‘very small’ and measured it to be 1.5 inches (3.8 cm). It is not known what size it was during Napoleon’s lifetime.” The item’s current owner has allowed only ten people to see it, and has apparently been offered over $100,000 for it.

Shortly after I bought the shop in November 2001, a customer asked if I could help him sell a document which he claimed contained irrefutable evidence that Napoleon had been poisoned, and had not—as history records—died of stomach cancer while exiled in Saint Helena. There was a whiff of the mysterious, bordering on questionable, and possibly with a foot in the illegal, about how this man had come to be in possession of the document, so, following repeated requests from him for help in selling the letter, I made a series of unconvincing excuses explaining why I was unable to assist in the sale of something that he could very easily have consigned to an auction himself.

This document must—if it was genuine—have been written by the same penectomist who removed Napoleon’s manhood. I have no idea what happened to the letter; it may well be languishing in a box somewhere, hopefully to be discovered in time—like a lost Caravaggio or Leonardo—and possibly to change our interpretation of history.

Such are the potential treasures that you invite into your bookshop when you throw open the doors every morning.

Not tonight, Josephine.

*

WEDNESDAY, 10 FEBRUARY

Online orders: 2

Books found: 2

Beautiful sunny day. Today’s orders were both from the poetry section—very unusual to have any orders from the poetry section, let alone two on the same day.

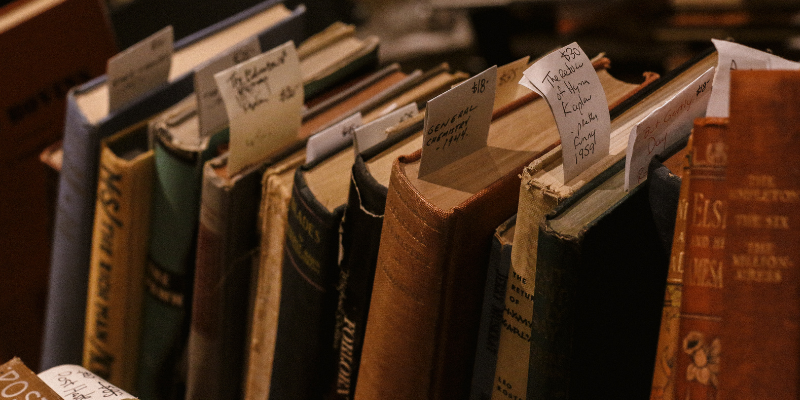

At 9.45 am my neighbor’s mother appeared and told me that she’s clearing her parents’ house in Dumfries and has a lot of books to dispose of. She told me that they’re in bundles, tied up with string. It’s odd how often books come into the shop contained this way. There are, essentially, four or five ways people bring books to the shop. The most common is in cardboard boxes, and generally this means of conveyance will contain the best books, and in the best condition. Then there is the plastic laundry basket, which usually means that the books are the relics of a dead great-aunt’s house, from which the best have been extracted and the laundry basket is the only means of transporting the books. It strikes me that it’s the emotional equivalent of getting the great-aunt’s coffin to the crematorium in an Uber.

After that there is the Tesco bag, which invariably means the books are slasher crime fiction. Then there’s the pile of bin liners, usually splitting, and brought in by a farmer, which inevitably contains dozens of copies of People’s Friends, Friendship Books and poor-quality fiction from between the 1930s and 1950s without dust jackets and—if lucky—with spines hanging on by a thread. Finally, there’s the bundled and tied with garden string category. This normally implies uniformity of size, which again, almost inevitably means that they are sets of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopædias or Harmsworth’s Home Educator. The kind of thing you never want to see as a bookseller, particularly after the tightly pulled string has damaged the covers.

A woman in a kaftan came in at 11 am and spent an hour telling me about how much she loves books, then left without buying anything.

Spotted a stone bollard with a hat propped on it on the way to the post office with the orders this morning. I can’t decide whether it was phallic or tragic.

Telephoned the woman in Maybole whose books I’m looking at tomorrow to check whether she’d be OK with Caroline, the photographer, coming along to take photographs as part of her project. She was quite happy about it.

A customer walked into the kitchen at 1 pm, while I was making a sandwich, and put the kettle on. He seemed strangely annoyed when I told him that it wasn’t part of the shop and asked him to leave.

Drove to Lockerbie to pick up Emanuela (aka Granny, who used to work in the shop). Dropped in on Galloway Lodge jam factory in Gatehouse of Fleet en route to pick up some apple boxes for tomorrow’s book deal. Galloway Lodge is owned by my friend Ruaridh, and the recycling bins are usually full of cardboard boxes which perfectly accommodate about twenty books each. Granny was waiting for me at Lockerbie, wearing a trench coat and smoking a cigarette, and looking every inch the film noir femme fatale. She looked at her watch and said, “Where you been, you fucking bastard?” I was three minutes late.

I doubt that the second-hand book trade is made up of a greater number of misers than any other business.Home just after the shop closed. Stayed up late chatting to Granny, who revealed that she’s going to write a book called Three Men and a Goat. She’s very fond of Jerome K. Jerome, but rather than three middle-class men gently rowing down the stream, this book is going to be about a homicidal woman who moves to Scotland and works in a second-hand bookshop. I’m not quite sure where the goat comes into it, but I suspect that there might be a sinister whiff of Aleister Crowley about it. At midnight she told me that it was her birthday, so we opened a bottle of champagne.

Till total £71.00

2 customers

MARCH

“The worthy man who taught me how to buy and sell books is now away from his old bookshop, and his stock has been scattered by the auctioneer’s hammer. He was very frugal, and indeed miserly. He amassed a small fortune, but lost it by publishing a newspaper, and the worry of it killed him.”

–R.M. Williamson, Bits from an Old Bookshop

*

There seems to be a literary tradition that booksellers are portrayed in fiction as being frugal: John Baxter in The Intimate Thoughts of John Baxter, Bookseller, to name but one. I like to think that it’s a question of circumstance rather than choice—not many of us make a sufficiently decent living to amass even “a small fortune” and by necessity are obliged to live fairly parsimonious lives which define us as poor, rather than miserly. I can’t think of any booksellers I’ve encountered who are anything less than generous with what little they have. The character of Henry Earlforward in Arnold Bennett’s splendid Riceyman Steps (published in 1923), though, is the perfect example of a miserly bookseller. Not content with selling his wife’s expensive wedding ring from her first marriage and buying a cheap one for his betrothal to her, he fell into a panic about her request to visit Madame Tussaud’s as a treat on their wedding day because of the ticket price:

Withal, as he extracted a pound note from his case, he suffered agony—and she was watching him with her bright eyes. It was a new pound note. The paper was white and substantial; not a crease on it. The dim watermarks whispered genuineness. The green and brown of the design were more beautiful than any picture. The majestic representation of the Houses of Parliament on the back gave assurance that the solidity of the whole realm was behind that note. The thing was as lovely and touching as a young virgin daughter. Could he abandon it for ever to the cold, harsh world?

Bennett describes Earlforward’s reluctance to spend money as a psychological “monster” which retreats when Violet, his bride, pays the additional fee to visit the Chamber of Horrors, although notably the “Relics of Napoleon did not interest them.” Perhaps if Maggs had sold the emperor’s penis to the museum rather than to an American book dealer, they might have had a very different day.

A woman in a kaftan came in at 11 am and spent an hour telling me about how much she loves books, then left without buying anything.I have no idea why it seems normal for people to imagine that second-hand booksellers are sitting on untold piles of wealth. I have friends who mistakenly believe that I am, and certainly customers who—when asked to pay £6 for a hardback that was £18 when new two years ago—are often vocal in their resentment. As always, Dylan Moran’s character Bernard Black, in Black Books, strikes the perfect note when a customer offers to pay £2 for a book that Bernard has priced at £3: “Because £3 is just naked profiteering for a book a mere 912 pages long. What will I do with that extra £1? Add an acre to the grounds? Chuck some more Koi carp in my piano-shaped pond? I know: I’ll build a wing on the National Gallery with my name on it.”

Even Williamson, most generous of spirit and purse, noted that

In works of fiction, the second-hand bookseller is a curious compound of imagination and reality. He is invariably an old man of a morose, unsociable temperament. He is of a sceptical disposition; last century he quoted from Voltaire, Hume, and Tom Paine, and nowadays he studies the higher critics. He is miserly, greedy, shabby, and utterly callous as to the world’s opinions. He is usually a widower; his charmingly lovely daughter and a black cat are the companions of his solitude.

Later on he comments that

I was at one time employed by a second-hand dealer in books who was the most miserly, miserable and suspicious man I ever came into close contact with. He dined every day in the back shop on rice and milk; one New Year’s morning he presented me with an orange, which was the only gift I ever received from him.

I truly hope that this myth has now been exploded—I doubt that the second-hand book trade is made up of a greater number of misers than any other business, but perhaps because very few of us make more than a subsistence living from it, and because most of us are the sole employee, we are quite visible to our customers in our morose, unsociable shabbiness.

*

TUESDAY, 1 MARCH

Online orders: 5

Books found: 2

My mother appeared at 11 to take Granny out for coffee. Once my mother had left the room, Granny said, “Ha ha, fucking bastard, now you have to do some work,” as she held the shop door open and let the cold wind in to add to my discomfort in her absence.

A woman in her late sixties, with black curly hair peppered with grey, and a faintly American accent, came in after they’d left with a man who I assume is her husband. He is probably around eighty. They visit two or three times a year and pile up books on the table by the fire, then sit in the leather armchairs in front of it and read for the entire day. They are both sweet, and kind, and if it’s a cold day like today I always light the fire so that they’re warm and comfortable. I don’t know their names, or where they’re from, but they clearly make a pilgrimage to Wigtown, always spend at least £50 and are incredibly polite about how much they enjoy coming here.

A couple from Girvan brought six boxes of pretty average books down at noon, a mix of fiction and non-fiction. Gave them £25 for a small pile.

The new weighing scales arrived, so I started to weigh the boxes for FBA shipment. When I lifted up the first box to weigh it, I found the missing scales underneath it.

Association of Wigtown Booksellers (AWB) meeting at 5.30 in Curly Tale Books, the shop next door, which specializes in children’s books. The discussion revolved—as it always does at this time of year—around the program for our Spring Festival. It would be far more interesting if there were arguments, banging of fists on tables and slamming of doors, but we all tend to agree and accommodate one another’s requirements.

Closing the back door of the shop this evening, I noticed that the pond is full of mating frogs once again. The sound of them when the back door is opened is almost deafening.

Sue from Atkinson-Pryce Books in Biggar called to order two more of the New Naturalists from the deal in Stranraer.

Till total £156.50

4 customers

__________________________________

Excerpted from REMAINDERS OF THE DAY: A Bookshop Diary by Shaun Bythell. Excerpted with the permission of Godine. Copyright © 2022 by Shaun Bythell.