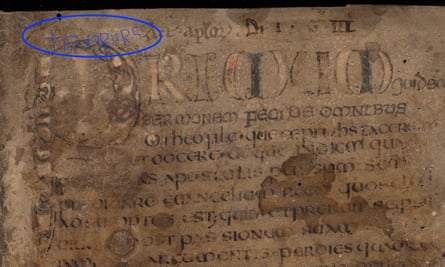

For nearly 1,300 years, no one knew it was there. The name of a highly educated English woman, secretly scratched on to the pages of a rare medieval manuscript in the eighth century, but impossible to read – until now.

Academics have discovered the Old English female name Eadburg was repeatedly scored into the surface of the religious text, using a method that kept it hidden from the naked eye for more than 12 centuries.

The covert writing of the woman’s name was finally revealed when researchers at the Bodleian Library in Oxford used cutting-edge technology to capture the 3D surface of the ancient manuscript, a Latin copy of the Acts of the Apostles that was made in England between AD700 and AD750.

It is the first time this technology, capable of revealing “almost invisible” markings so shallow they measure about a fifth of the width of a human hair, has been used to record annotations on the surface of a manuscript.

“There are only a limited number of surviving early medieval manuscripts which contain clear internal evidence of a woman having created, owned or used them,” said Jessica Hodgkinson, a PhD student at the University of Leicester who made the discovery while researching her thesis on women and early medieval manuscripts.

“Most of these manuscripts are from the continent – it is much rarer to find evidence of this in surviving manuscripts which were made and used in the geographical area we now call England.”

Writing Eadburg’s name on the book quietly asserted her power and high status at a time when only a few elite, highly educated women were able to write and read both Old English and Latin. “It’s a hugely significant and very powerful text – the word of God, conveyed through the apostles. And I think that might be at least part of the reason why somebody chose to write Eadburg’s name into it, so that she was close to that.”

It is not clear why the name was written so stealthily, with a drypoint stylus, rather than ink. “Maybe it was to do with the resources that person had access to. Or maybe it was to do with wanting to leave a mark that put that woman’s name in this book, without making it really obvious,” Hodgkinson said. “There could have been some reverence for the text, which meant the person who wrote her name was trying not to detract from the scripture or compete with the word of God.”

The imaging work was carried out at the Bodleian Library by John Barrett and the ARCHiOx project team. Significantly, they found Eadburg’s name passionately etched into the margins of the manuscript in five places, while abbreviated forms of the name appear a further 10 times.

This suggests it is likely to have been Eadburg herself who made the marks. “I could understand why somebody might write someone else’s name once. But I don’t know why you would write somebody else’s name so many times like that,” Hodgkinson said.

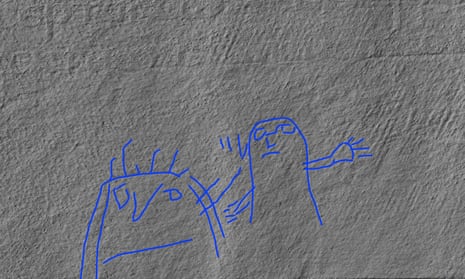

An Old English transcription, and tiny, rough drawings of figures – in one case, of a person with outstretched arms, reaching for another person who is holding up a hand to stop them – were also discovered etched on to the small book, which is barely bigger than an A5 pamphlet.

after newsletter promotion

Hodgkinson hopes further study will reveal the meanings of these figures and the ancient transcription, which has so far proved impossible to translate.

She also hopes to eventually discover who Eadburg was. Certain features of the manuscript suggest the book was produced in Kent, where a woman called Eadburg was abbess of a female religious community at Minster-in-Thanet in the mid-eighth century. However, there are at least eight other known contenders for the role.

But whether or not these mysteries are ever solved, for Hodgkinson there is something very empowering and meaningful about the discovery of Eadburg’s name. “Still, to this day, there’s this human urge to leave a mark of your presence on something that is meaningful to you or is a record of where you’ve been,” she said. “We don’t know all that much about Eadburg, but now, because of this amazing technology, we’ve seen her name, we know she was there. She’s here, in this book – and it speaks across the centuries.”