I have never written about my chest, which seems bizarre given that I’m a writer and I process everything by writing about it. I’ve been living in this body for 34 years, and had the tissue I’m having removed for roughly 21 of them. During those 21 years I’ve taken dozens of workshops and written hundreds of pages. I’ve written about my relationship with my grandmother, my experience in locker rooms, my love for Bruce Springsteen. I’ve written about my feelings on marriage, my performance anxiety, a particularly memorable Greyhound bus ride. I’ve spent a year and a half in an MFA program, where all I do is write.

And yet: I’ve never written about my chest. Not for the nineteen years I’ve been thinking about having this surgery. Not when I had my first consultation, when I was eighteen, or when I finally booked the date, seven months ago. Not even when I was fourteen years old and put on a binder for the first time. You couldn’t have torn me away from the mirror that day—I stood in my bedroom for I don’t know how long, marveling at the way my white T-shirt fell against my flat chest. There is no word for the pleasure of seeing yourself as you always imagined yourself to be, but that is exactly what I felt, looking into the blue plastic-framed glass in my childhood bedroom. Ecstasy comes close; euphoria is the word we sometimes use. Perhaps it is even simpler, though: I loved the way I looked. It had never occurred to me, before this day, that this was a feeling I could have.

Until now, I’ve never written about this part of my body that joined me on this planet some two decades ago and soon will depart again, its stay with me only temporary, as it turns out. As I write this, I am 51 days from surgery; by the time you are reading it, I will be on the other side, an entire era of my body having come to a close and another begun. I am only now realizing: I have something to record, a certain existence to capture before it disappears forever. I’m scrambling, scribbling hastily down the barrel of 51 days, trying to preserve not the body, but the space.

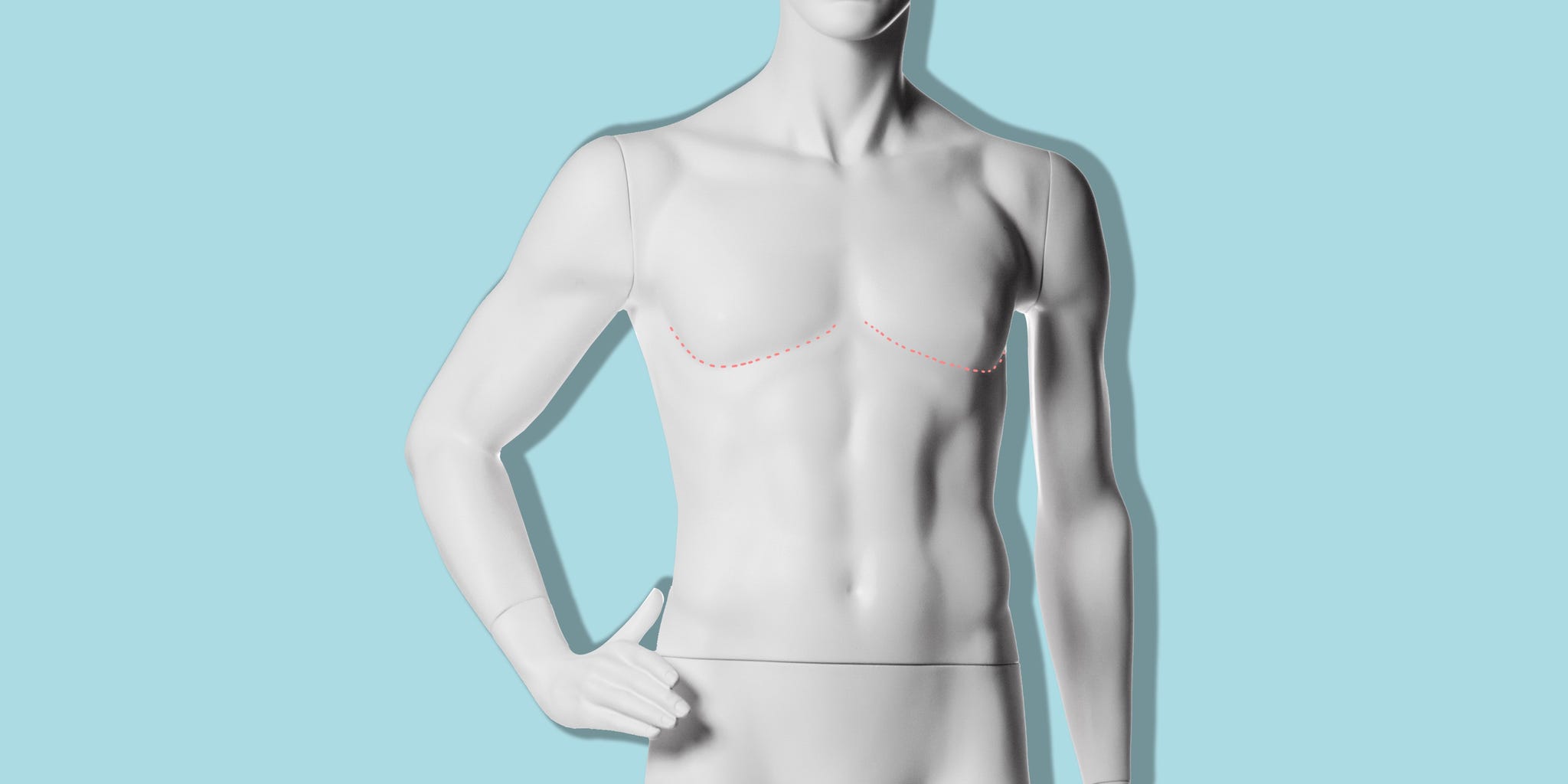

My grandmother calls it my “upper job.” That’s how she refers to the surgery I’m having in a little over eight weeks, when a plastic surgeon in Florida will cut two long, curving lines across my chest and remove some two to five—probably closer to five, because I’m not small—pounds of breast tissue. The first time she said it, we were driving on the highway, with me behind the wheel and her in the passenger seat.

“I was thinking about your upper job,” she said.

My... upper job. What? I scoured my brain for what she could possibly be referring to—my teaching position? A job coming up after I finish graduate school? I couldn’t even begin to place it.

“Where in Florida is that surgeon, anyway?” she said.

My upper job. I told friends the story for weeks afterwards. One of the lovely consequences of the fact that English is not my grandmother’s first language is that she comes up with her own creative ways of saying things. A local restaurant, Rogue Cafe, has been permanently renamed The Scoundrel in our family. A neighbor’s dock gets christened Jones Beach, in a nod to how crowded it is. Petting the dog is “making nice to” her. Somehow, my grandma’s nomenclature always manages to capture the essence of a thing. Often, it does so even better than the original name.

Top surgery: upper job. When I first told my grandmother I was having surgery, I worried about what her reaction might be. I told her I knew she might be upset, and that I had been afraid to tell her for a long time.

“I’m not so upset,” she said, sitting across the table from me in her Brooklyn kitchen. “And listen. You should never be afraid to tell me anything.”

My grandmother had an excess of miles, which the airline told her would expire if she did not use them. She wanted to give them to me—maybe you can go somewhere, she said—but I had no trips coming up, nowhere to go, nothing to spend the soon-expiring miles on. She wanted me to have them, though. A child of the Holocaust, she’s spent her life being thrifty, allowing herself little, and nothing brings her more pleasure than gifting her grandchildren abundance.

Way down on the airline’s website, I noticed an alternative: miles could be spent on TSA PreCheck, the Transportation Security Administration program that allows travelers who’ve been vetted by the government to bypass some of the most stringent security measures at airports—including, crucially, the body scanner.

“Nana,” I told my grandmother. “I don’t need to go anywhere. But you know what might be really helpful?”

“Yes! What?”

“I can get a PreCheck membership,” I said. “Every single time I go through the airport, I end up getting patted down, because they can’t tell if I’m a man or a woman and it confuses their machine. If I had PreCheck, I wouldn’t have to go through that… it would make a huge difference for me.”

“Do it,” she said, thrilled to be able to help.

TSA screening was never a pleasant experience for me, or arguably for anyone, but things got significantly worse when they introduced body scanners twelve years ago. I was always stopped, and an identical chain of events would always ensue: a flag from the scanner, instructions to step aside, and then a male TSA officer approaching and explaining to me that because the machine had detected an aberration in the chest area, he would just be using his gloved hands to give me a basic pat-down. Down they would go along the sides of my rib cage where my binder, invisible beneath my shirt, squeezed me in. And then along the front, the backs of his hands tracing my compressed chest, which appears from a distance to be a well-developed set of pectoral muscles but, with careful touch, reveals itself to be something else. It was usually at this point that he would realize I wasn’t male, and then some combination of apologies and discomfort would tumble forth, and a female officer would take over. The fact that I could predict every step of the process didn’t make it any less humiliating. I, who generally love flying, began to dread the airport.

Soon after the arrival of the body scanners, my family flew through Amsterdam for vacation. The security officers at the airport, visibly unsure of my gender but too uncomfortable to ask, tried to solve the puzzle by asking for my identification. They examined it together, their heads nearly touching as they looked down at my passport. Then one of them looked up at me and laughed. What is there to say about this moment? My face felt like a tiny, invisible sauna had spontaneously sprung up around it. I wanted to drop straight through the floor into the airplane hangar. You know your status as a human is bad when your identification—the very document that confirms your existence—is a source of comedy. When the female officer patted me down, my father stood as close as they would allow him, never once looking away as I raised my arms in the air and spread my legs so that the officer could run the back of her hand up the inside of my thigh.

It was Shadi Petosky, a trans woman whose tweets about her treatment at the hands of the TSA went viral in 2015, who alerted me to the reason the body scanner was flagging me every time. Petosky was detained, isolated in a private room, and subjected to several extended searches, eventually missing her flight because the body scanner had detected an “anomaly” in her crotch region. (“Anomaly” was, at the time, the TSA’s official language for body parts that do not align with the machine’s expectations. Months later, the Administration announced that it had chosen a new word: “alarm.” Despite the Administration’s change in policy, I am still planning to custom-order a TSA ANOMALY T-shirt one of these days.)

Petosky’s experience revealed a vital detail in the TSA process that had previously been opaque to me. When the traveler steps into the body scanner, the attending agent must press a button on their screen: either female or male. Another agent in a separate room then examines a scan of the body in the machine, comparing it to what the TSA considers prototypical male or female anatomy. Any inconsistency—a mass in the chest area of a male body, for example—is flagged for further inspection. He may, after all, have a bomb strapped beneath his shirt.

Once I figured out why I was being patted down every time I flew, I adjusted my practices. When I stepped into the machine, I’d turn to the agent and say, “Make sure you press female.” Or: “I’m female, just so you know.” Occasionally the officer would express offense at the implication that they wouldn’t otherwise know. Other times they’d just nod, seeming to appreciate the heads-up. Often, they were surprised. There is nothing dignified about stepping into a body scanner and announcing your anatomy to anyone within earshot, but it was better than getting patted down every time, and the patting down stopped.

Now that I have PreCheck, I don’t have to tell anyone which button to press on a screen. PreCheck travelers pass only through a metal detector—an old-school, gender-neutral device. As long as I don’t have any metal on my person, I get nothing more than a nod from the officer on the other side, and I’m on my way. But plenty of other people get sent back to try again: those who have neglected to take off their belts or many bangles; those who have left their keys and money clips in their pockets. PreCheck passengers do not have to take off their shoes, but once, I walked through the detector with my Timberlands on and it beeped. I knew right away it was the steel shank in my boots, so I took them off and sent them through the machine that inspects luggage. Now if I find myself flying in boots I remove them without hesitation. You don’t have to take your shoes off, some agents say to me, not without a touch of irritation. They think I’m clueless, I know. They don’t realize that it is in fact the opposite: in this space, I am an obsessive observer of protocol. I will do anything to avoid attention.

I hate rules, and I hate authority. As a teenager, I had NO GODS NO MASTERS inscribed on a good portion of my belongings. But being trans often feels, to me, like moving through a world where there are invisible rules that I am always breaking. Perhaps this is why I feel like a chipmunk, or a bird—some skittish, hypervigilant animal. I wash my hands quickly in the bathroom; I am sheepish with hotel clerks and bouncers. I worry too much about being underdressed at weddings. I expect security guards to stop me. One way of saying this is: I always feel that I am on the verge of being in trouble. And of course, I am. Since I was born, there’s been one big rule that I can’t stop breaking.

I’ve started sleeping shirtless. This is new; up until recently, I always slept with a shirt on. And when I am sharing my bed with someone else, I sleep in my binder. (If I’m wearing my binder and nothing else, I call it “Donald Ducking,” after the cartoon character who is always wearing a shirt, but no pants. I will not miss Donald Ducking.)

But now, alone in my apartment, I have started throwing my T-shirt into the washing machine before I go to sleep. Then it is just me, my underwear, and my chest. I climb into bed and lie almost naked under the sheet. I think about how in just a couple months, I’ll get into bed this way every night. And once the incisions are healed enough, I’ll start rolling over, because I’m a stomach sleeper, one who spends the night with my face pressed into the pillow and my belly flush with the bed. I sleep that way now, of course; but soon, there will be nothing between me and the fitted sheet—just me.

Like a lot of kids, I loved being shirtless. Jeans and no shirt, shorts and no shirt. My favorite was to put my T-shirt on and then pull it over my head and behind my neck, my arms still in the armholes but my chest exposed, so that I looked like some kind of eight-year-old frat boy showing off his pecs. I even got my brother, four years younger and for a time a miniature version of myself, into it too. We’d amble around the house with our T-shirts bunched behind our necks, our skinny chests bare, singing our theme song, which had only one repeated phrase: “Me and my buddy; me and my buddy.”

There is a picture of me and my twin sister in our backyard. We’re probably about five years old. My sister, femme from the time we could walk, wears a plaid dress and pink sneakers. I’ve got on white sneakers, electric blue shorts, and no shirt. I’m grinning. My little kid body hasn’t developed any muscle or fat yet. My tiny ribs show through; my arms, holding a doll on my shoulders (perhaps we were playing house, in which my sister was always the mom and I the dad), are flexed but scrawny. My nipples are right at the edge of where my pecs would be, if I had any. In a little less than a decade from the time this picture is taken, my chest will begin to change.

Sometimes I find myself idly imagining that what I am doing is returning my body to its rightful state—to the version of me that was, before everything transformed, before something appeared that I will now take off. That would be a mistake to believe, though. I will not have a tiny kid body when this is all over; my nipples, if they manage to survive being grafted back onto my skin, will sit above two long scars. One of the gifts of childhood is a limitless imagination and a limited understanding of possibility. As a child, I always assumed I’d grow up to be a man—to look like my father, not my mother. To grow pectoral muscles that were not hidden by breasts. This did not happen, and I am not chasing the child who believed it would. But I am, perhaps, chasing the grin in that picture. I’ve been plodding forward, not even knowing how much I was missing it, for a long time.

Lying in bed now, I look at my chest. The tissue has been broken down by nineteen years of binding. I have a birthmark just below my left collarbone. It vaguely resembles the shape of the United States. It’s visible in all the shirtless pictures of me as a kid, and I think it is high enough that it will remain on my body after surgery. I hope it does.

I never hated my chest. It’s a perfectly fine chest; a good one, and I’m fond of it, even. It’s been with me for some 21 years. Everywhere my body has traveled, it has come along. Everything I have done, it has done too. It has been a part of me, and in some ways, it always will be. It needs to go now, not because it is wrong, or something worth despising, but simply because it is standing in the way of a life I can no longer postpone.

I’ve been pulling on a binder after I shower for 6,935 days, but it is only now, 51 days out from surgery, that it seems to be getting hard. Every time I step out of the tub and look at my binder—my skin still damp, the air heavy with steam—I feel almost incapable of putting it on. My mom says it’s because I can finally afford to be fed up with it, finally afford to despair. There is an end in sight, which means it is now safe to allow in the acknowledgment that this is unbearable.

I consider myself lucky that this is a new feeling; until now, binding has never felt unbearable to me. The tight edges of the binder leave marks on my skin sometimes, yes, and occasionally I wonder whether I might breathe more deeply if I weren’t wearing it. The worst part is the constant adjustment; the way something’s always escaping, or something else digging into me. I am always a little uncomfortable.

But even discomfort can become familiar, if you feel it long enough. You can forget that anything else exists. Every morning for the last nineteen years, I’ve stepped into a binder—far easier than trying to pull it over my head—and tugged it up to my torso. I feel then like I’m strapped in. It’s tight, but it’s also holding me. More than anything, it feels normal.

I look often, in these last days before surgery, at the binders hanging from hooks on my closet door. They are shaped like tank tops that end just below your chest; they are made of a thin, compressive material. I have about four of them at any given time, and when they become torn and threadbare from being used every day, I trash them and order more. When I first started binding nineteen years ago, I mostly wore white ones; a few years ago, a girlfriend told me she thought black binders would look sexy, and now that’s mostly what I wear. I agree with her; I never feel sexy in a binder, but I feel slightly less like I’m wearing a hospital garment when it’s black.

A friend who’s had top surgery texted me recently, warning that being without my binder might feel overwhelming at first. “A binder had almost become a comfort,” he wrote, describing the adjustment in the days after his own surgery, and I knew what he meant immediately. Is there any object that’s been more consistent in my life than my binder? Nothing, and no one, has been physically closer to me than this vest that’s been pressed against my skin for the majority of the last nineteen years. It’s hard to believe, after almost two decades of buying them, wearing them, washing them, storing them, and replacing them, that a binder will never hang in my closet again.

When I tell people I’m having top surgery, some of them are surprised. I didn’t know you were considering it, they say. Oh, I have been, for about nineteen years, I tell them, and that usually stuns them into silence.

What does it mean to consider something for nineteen years? What does it mean to live in a body for nineteen years that feels so misaligned that you compress it every single day? That you cannot allow your lovers to see it, because if they did, they might stop seeing you? I once thought that this was a solution. Binding works reasonably well for me, that line of thinking went. Why have a $12,000 surgery when I can just keep replacing a $30 undergarment every few months?

Other times, I thought the same thing my father said to me when I told him I’d decided to have surgery: “I had been wondering… is Naomi just going to wear that vest for the rest of her life?”

Decide: it comes from the Latin words de, off, and caedere, to cut. Taken together: to cut off.

I asked a therapist once: “What if I want to wear a bikini?”

She suppressed, I’m sure, the amusement that must’ve risen somewhere inside her. She was a good therapist.

“Well, first of all,” she said. “You can wear a bikini after top surgery if you want.”

“I know,” I said, impatient. “But, you know.”

“Okay,” she said. “Let’s go with this. If you were going to wear a bikini… what kind of bikini would you wear? No, I’m serious… what would it look like?”

I remember thinking … beige?

In a way, that said it all. I laughed, and then she did, too.

“I guess I can’t actually imagine ever wanting to wear a bikini,” I said. I felt stupid for having asked the question, but she could tell, and stopped me.

“You’re the kind of person who needs to turn over every stone, Naomi. That’s okay. So now we know: you don’t think you’ll ever want to wear a bikini. And if you do, you can.”

Bikinis don’t move me. But swim trunks do. Years ago, my college girlfriend’s mom tossed a men’s surfwear catalog onto my lap. We were sitting on her back porch in summer, Michelob Ultras in hand. The family chocolate lab, Talon, lay at our feet.

“You should pick out some boardshorts,” she said. “You wear boardshorts, don’t you, Naomi?”

She had never known an out queer person before her daughter came out to her and brought me home the same month. But she had always seen me for exactly who I was, without the intervention of “diversity trainings” or brochures, and now I was moved that she understood this part of me without needing an explanation. Flipping through the pages of boardshorts, I ached. All I have ever wanted, for as long as I can remember, was to go swimming with no shirt on.

My TSA PreCheck membership will expire in about a year. In theory, I will no longer need it. If I step into a body scanner and say nothing to the agent and they press the button for male, it won’t matter. There will be no mass on my chest, no binder holding it in, nothing to alert the officer sitting in a separate room that a seemingly misaligned body has crossed the scanner’s threshold.

Other misalignments will arise, though: other checkpoints, other alarms. These days, when I walk into a women’s bathroom and am perceived as an intruder, I puff out my chest, pitch my voice high. In moments of desperation in locker rooms, I’ve thrown off my shirt, and all questions are instantly settled. It’s a privilege to have the body that is presumed to belong in a space, and for now, I do. That will change. All my life I’ve heard children ask their parents whether I am a boy or a girl. That will not.

The rules will only get more broken. If the TSA introduces a new scanner, I’ll be in trouble all over again. And no matter what, I’ll bear scars that mark the end of a 6,935-day journey, and the beginning of a new one. Scars that say, Something had to be decided. Something has been cut off.