/media/cinemagraph/2022/10/05/siegfred-newanimation4.mp4)

The Improbable Rise and Savage Fall of Siegfried & Roy

At the peak of their fame, they were arguably the most famous magicians since Houdini.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

he last survivors of a lost empire live behind the Mirage, in Las Vegas, out back by the pool. On a good day, Siegfried & Roy’s Secret Garden will draw more than 1,000 visitors, the $25 adult admission fee justified mostly by the palm shade and tranquility it offers relative to the mania outside its walls. There are also long summer stretches when it’s 100 degrees and things get a little grim. During a recent visit, only a few families strolled through, surveying the five sleeping animals on display: three tigers, a lion, and a leopard. The Secret Garden ostensibly operates as an educational facility. “Look, a lion,” one young father said to his son, while pointing at a tiger.

Yet residual magic remains. The best time to visit is late afternoon, just before closing, when the heat has started to subside and the sleeping cats stir. If you’re lucky—in this city built on the premise that you, against all odds, will be lucky—a tiger will roar when you’re standing nearby. A tiger’s roar is more than audible. You feel it in your chest, in your teeth, in the prickles of your skin. And if you turn to look at its source, you might catch a tiger’s gaze, its haunting eyes staring into yours, tracking your every move, knowing what you’re about to do before you do it.

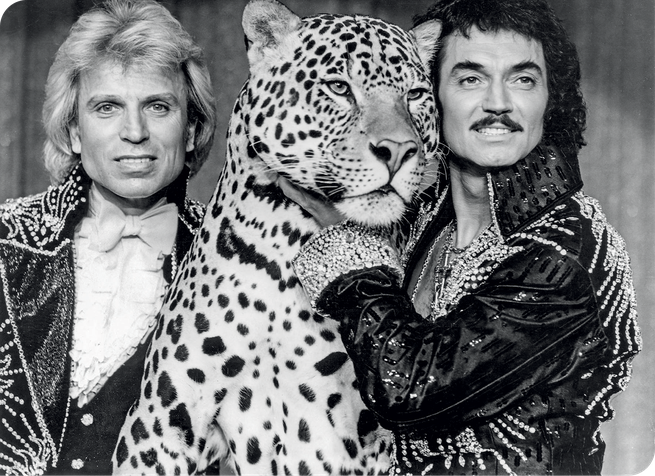

At the peak of their particular and possibly extinct brand of celebrity, Siegfried & Roy were arguably the most famous magicians since Houdini. They were without question the most famous German magicians performing with a large collection of apex predators. Depending on when you enter and exit their story, it’s either triumphant or tragic, surprising or inevitable. It can serve as a testament to the power of lies, including the ones we tell ourselves, or a cautionary tale about fiction’s limits, especially when fact takes the form of a fed-up tiger. Now it’s about to reach its sad, instructive conclusion, the way so many modern fables end: with a corporate takeover.

In December 2021, Hard Rock International agreed to pay MGM a little over $1 billion for the right to operate the Mirage, including a three-year license to the name. For a little while longer, the hotel will continue to be marketed as a desert oasis, and its iconic volcano will still erupt. But Las Vegas is the least sentimental city on Earth, and Hard Rock has already announced plans to reimagine the property, including by building a guitar-shaped hotel like the one it opened in Hollywood, Florida, in 2019. The Mirage—the hotel that changed Las Vegas—will vanish from the Strip around the time it turns 35 years old.

It’s less obvious what will happen to the Secret Garden or its inhabitants, which include a few dolphins as well as the cats. There were once more than 50. Today, 14 remain, including Leni, a leopard; Maharani and Star, striped white Bengal tigers; and Timba-Masai, the “White Lion of Timbavati.” They’re put on display in shifts, mornings and afternoons, shuttled between their exhibits and their kennels in a complex the size of a football field. The animals have never known another home, and some of their human caretakers have worked here for more than three decades. Employees greet one another with the same worried question: Have you heard anything? No one has heard anything. There is a singular certainty in the Secret Garden: Its breeding program ended years ago, and so, one by one, its population will continue to decline. The only question is when, exactly, it will reach zero.

The fate of the larger-than-life statue of Siegfried & Roy—enormous busts of their perfectly coiffed heads, framing one of their beloved tigers—is also unknown. The statue has a precarious-seeming place on the stretch of the Strip between the Mirage and Treasure Island. When Roy died in May 2020, mourners placed flowers, notes, and candles at its base. They did the same when Siegfried died seven months later. People still stop to take pictures, careful to crop out the homeless man who sometimes makes camp on the sidewalk nearby. The statue has been painted to look like it’s made of bronze, but there are enough cracks in the paint, particularly on the tiger’s sunbaked nose, to reveal that it’s not. It’s hollow, and wouldn’t take many men to move.

It’s almost hard to fathom, these less credulous days, but there was a time when two sons of damaged German soldiers could put on gemstone-laden capes and codpieces and do corny tricks in the company of some magnificent animals and rank among the best-known and wealthiest entertainers in the world. In June, before an auction of some of Siegfried & Roy’s belongings—including jewelry, tiger-themed artwork, and their matching kimonos—the Los Angeles Times decreed: “It’s not possible anymore to be famous and moneyed the way Siegfried & Roy were famous and moneyed.” Their magic word was SARMOTI, which stood for “Siegfried and Roy, Masters of the Impossible.” They must have sometimes looked around and believed it.

Siegfried Fischbacher met Uwe Ludwig Horn, later known as Roy, on a German cruise ship named the TS Bremen in 1959. Siegfried was 20 years old, strong-jawed, and working as a first-class steward. On certain evenings, he assumed a different name, “Delmare the Magician,” and performed for passengers. He had been practicing since he was a child, and claimed that the first time his shattered, alcoholic father acknowledged him was after he made a coin disappear: “How did you do that?” his father said. Siegfried spent the rest of his life chasing that feeling.

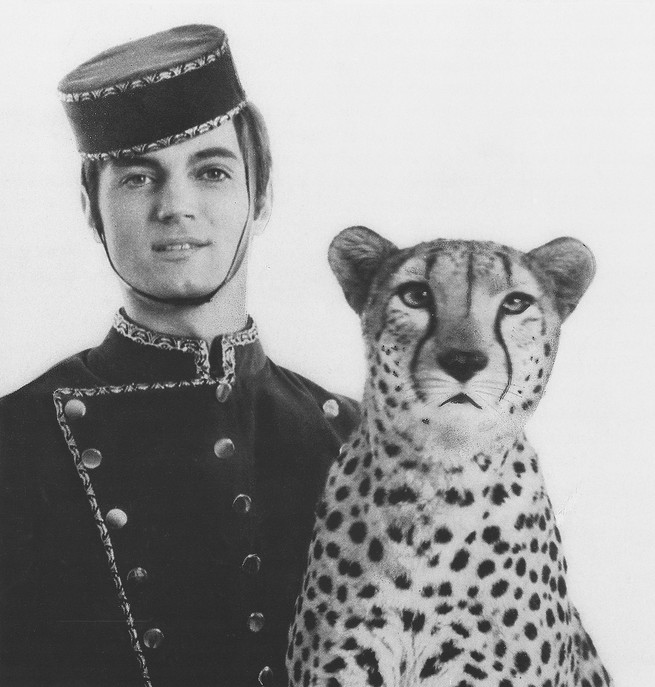

Roy was five years younger and hungry for adventure, having abandoned school and an equally unhappy childhood to work as a bellboy at sea. He had filled his own absence of paternal affection with animals and fantasy. Roy claimed that his boyhood dog was half wolf, and that it had once rescued him from quicksand.

One night on the ship, Roy watched Siegfried perform his magic and didn’t seem impressed. However technically gifted Siegfried appeared, however handsome he was, his tricks were tired and ordinary, devoid of surprise or flair. His show included a hat, and the hat included a rabbit.

“If you can make a rabbit disappear,” Roy asked, “could you do the same thing with a cheetah?” Siegfried said yes.

Not long after, Roy beckoned Siegfried to his cabin across the corridor. Roy opened his door. Inside, a huge cat was waiting for them. The cat was named Chico, and he was, undeniably, a cheetah.

Roy looked at Siegfried, who was appropriately stunned. “Where there is trust, there is love,” Roy said, and Siegfried chose to believe him, as if to prove the point.

Over Siegfried & Roy’s next six decades together, the nature of their relationship was always purposefully opaque. Sometimes they appeared to be friends, sometimes lovers, sometimes rivals. With each other, they had no secrets. “They literally communicate onstage with a glance,” their manager Bernie Yuman has said. They knew each other better than many of us know ourselves. Siegfried, the blond one, was the magician, the engineer, the perfectionist, the restraint. Roy, with his jet-black hair and occasional mustache, was the animal whisperer, the dreamer, the fabulist, the spark.

They did their first show together, along with Chico, on board the Bremen. Siegfried performed the magic, Roy was his unorthodox assistant, and the cat acted very much like a regular cat, only significantly larger and more dangerous. The captain was not pleased that a teenage bellboy had smuggled a cheetah onto his ship, but the audience loved it. Siegfried, Roy, and Chico became a shipboard staple.

The trio later bounced around Europe, building a following in adult playgrounds like Monte Carlo. Their act consisted of simple, classic tricks, like someone getting into a box, then disappearing, then reappearing a few moments later. But the young Germans performed each illusion with a signature precision—and a 100-pound cat. Crowds especially adored Chico, who sometimes won top billing on flyers.

In 1967, a talent scout asked them to come to Las Vegas, where a slightly more down-market version of the Folies Bergère—the Parisian revue where Josephine Baker became famous—was establishing itself at the Tropicana. The idea of a hot ticket in Mob-run Las Vegas was Frank Sinatra belting out tunes next to a coked-up Sammy Davis Jr. and a line of topless showgirls with feather headdresses. It wasn’t clear how well a pair of swashbuckling German magicians with a cheetah, none of whom spoke English, might appeal to the cigar-chomping set. Siegfried & Roy were placed 14th on a long bill, between some strongmen and a comic xylophonist.

Siegfried didn’t much care for Las Vegas at first, and he began campaigning for a return to Europe. Roy spent the rest of his life trying to make Siegfried feel more at home, as though nervous that his partner might one day decide to leave. They moved into a mansion they called the Jungle Palace, just north of town. It was Moroccan-themed and stuffed with curios from around the world. (Siegfried & Roy were never “out” in the modern sense, but they lived together in some capacity their entire adult lives.) The library has a button that opens a secret door as a hidden speaker announces “SARMOTI!” A massive mural over Siegfried’s bed features a young, nude version of him holding two cheetahs on chains, staring down an evil sorcerer. Later, Roy turned 80 acres of desert into a sprawling compound called Little Bavaria, so artificially lush that Siegfried could close his eyes and imagine he was back in Germany, listening to birdsong.

Before they could afford to build their own sanctuaries, they took frequent drives to California to perform along Venice Beach. There, they met a young bodybuilder who also dreamed in German.

Like Siegfried & Roy, Arnold Schwarzenegger had a father who’d been left in ruins by the war. Like Siegfried & Roy, Schwarzenegger had found solace in an unlikely obsession. Schwarzenegger’s chosen distraction was his own body, and he sculpted it at Muscle Beach. In the early ’70s, Venice was a kind of way station for people who wanted to be amazing at some small, strange, pretty thing. Schwarzenegger remembers meeting brilliant chess players—Bobby Fischer played with his feet in the sand—and wandering mystics and Cheech and Chong, another future-famous duo, who were “running around on the beach, getting stoned out of their fucking minds.” Every one of them had grandiose, impossible aspirations. Siegfried & Roy still managed to stand out.

“They were always unbelievable,” Schwarzenegger says. “It was a straight 10, everything from beginning to end, always, with them.” Schwarzenegger says people back home laughed at him for his ambitions; he can only imagine how people must have responded to Siegfried & Roy when they dared confess their own secret plans. “And then they come over here and make their dream a reality,” Schwarzenegger says. “Only in America.”

The three transplants stayed close, Schwarzenegger often driving his mother to Las Vegas to see them when she came to the U.S. “They were experts with mothers,” Schwarzenegger says. Each visit, his old beach buddies would dote on Schwarzenegger’s mother a little more grandly, putting their latest tiger cub into her hands, hiring professional photographers to take portraits of her and her son and a cat, their inherent generosity now gilded by the spoils of some newly conquered territory. First they ascended at the Tropicana, until they became the grand finale. Then Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal—the inspiration for Robert De Niro’s character in Casino—brought the entire show over to the Stardust in 1978, where they used their newfound leverage to see their names on a Las Vegas marquee for the first time. (Rosenthal also threw in a silver Rolls-Royce that, according to Siegfried, he’d originally bought as a gift for his wife.)

In 1981, Siegfried & Roy moved again, this time to the Frontier, where they headlined a variety show called “Beyond Belief.” They rode out their extremely ’80s version of the ’80s there. Barbra Streisand, Elizabeth Taylor, Sylvester Stallone, Dolly Parton, and Robin Williams came to see them perform. Michael Jackson wrote and recorded “Mind Is the Magic,” which would become their theme song, as a personal favor. They were granted audiences with no fewer than three presidents—Carter, Reagan, and the first Bush—and, for good measure, Pope John Paul II.

For most people, that might have been enough. For Siegfried & Roy, there was no enough. One day in 1986, a developer named Steve Wynn announced that he was going to build the first new hotel casino in Las Vegas in 15 years. Wynn had been quietly assembling an enormous property on the Strip: 110 prime acres just north of Caesars Palace. He didn’t have a name for it yet, but he already knew that it would have 3,000 rooms, making it one of the largest hotels in the world. Siegfried & Roy liked the sound of that. A meeting was arranged. The three men sat down and hatched a plan.

Siegfried & Roy had always felt constrained by the venues in which they performed. Their professional homes were prebuilt, designed to accommodate someone else’s lesser ideas. At the Stardust, they’d had to persuade Rosenthal to cut a massive hole in the theater ceiling to make way for a new illusion. Now Wynn was going to build a monument from scratch. If he also built Siegfried & Roy a theater—a $30 million theater with 1,500 seats, custom-made to their ridiculous specifications, with a two-bedroom apartment upstairs and a stage big enough for a giant mechanical dragon—together they could put on a new kind of Las Vegas show, a spectacle, dramatic and gorgeous, one that families could attend, without crudeness or nudity or sin, just magic, great big beautiful magic. Siegfried & Roy would perform there and only there for the rest of their careers, becoming more than entertainers in the process. They would become a vision, an idea, a thumbtack in the mental maps of people all over the world. And they would make Las Vegas into something grander than a row of glorified gambling halls. They would turn it into the place where dreams really did come true: the Mirage.

Wynn’s grand design, and Siegfried & Roy’s forever home, would open in 1989. Wynn’s new partners had three years to get ready. For the last of those before years, Siegfried & Roy hit the road, playing Japan, playing New York City, cementing their global reputation while stoking a kind of anticipatory fire in Las Vegas, so that when they returned it might feel less like a move across town and more like an arrival.

“Without Roy, Siegfried wouldn’t be enough,” a woman named Lynette Chappell says. “And without Siegfried, Roy would be too much.”

Nobody knew the two men the way Chappell did. She grew up in Kenya and what was then Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, moving to Las Vegas as a dancer when she was only a teenager. Some fateful evening, she idled in the seats during rehearsals for a new variety show at the Stardust. Siegfried & Roy, still in the opening stages of their fame and English proficiency—according to Roy they eventually learned the language in part by watching The Flintstones—did a little silent magic, accompanied by their faithful cheetah and now also a leopard. The animals reminded Chappell of home, and she was nearly as struck by the two intense Germans trying to make names for themselves in the desert. She bonded especially with Roy over their love of big cats, and volunteered to look after the animals whenever assistance was required.

Chappell’s offer was the start of a permanent collaboration. For years, Siegfried had made Roy disappear, which meant that Siegfried alone remained onstage to receive the standing ovations. Roy didn’t like that very much. The two men needed a foil, so that they could both share in their audience’s admiration. “They decided they needed a victim” is how Chappell puts it. She became the “evil queen” who got levitated and sawn in half. Later, she followed them to the Frontier, and finally to the Mirage, watching their universe expand from her place very near the center of it.

The show at the Mirage was an immediate, unrelenting success. Wynn erected a massive billboard out front: Magicians of the Century. Siegfried & Roy played two shows a night, six nights a week. They were good for nearly 800,000 butts in seats a year, each audience member having paid as much as $100 for the privilege. For Wynn and the Mirage, that added up to more than $40 million annually. For Las Vegas, it meant many millions more in hotel rooms, meals, taxi rides, and gaming. Most of the old casinos, the places where Siegfried & Roy had become famous, fell to wrecking balls, clearing the way for dressed-up mimics of the Mirage: Excalibur, Luxor, New York–New York, Paris, the Venetian. Each had anchor entertainment tenants. Many of them were magicians.

Siegfried & Roy and their 250 human employees performed under an almost obscene amount of pressure. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, there was often tension at home and backstage. Asked if she ever felt fear around the cats, Chappell laughs. “No, no,” she says. “It was a lot safer for me to be in a small space with a cheetah or a tiger than with Siegfried or Roy.” Roy’s principal method of communication was shouting, regardless of his mood. But when someone screwed up around one of his animals, his voice would get lower. I wish to bring to your attention that you’re upsetting a goddamn tiger.

Siegfried’s sometimes-ferocious moods were usually triggered by Roy, who was both an inescapable presence and impossible to tame. Siegfried so craved the adulation of his audience that some nights he’d wander into the crowd before the show, hiding behind a mask, stealing energy from his buzzing fans. His pathological need for praise, and his constant fear that it might be withheld from him, meant that he could be set off by tiny errors of timing or effect that only he saw or perceived. Even in the chaos of a packed house, he noticed if a single light bulb was out, his eye wandering to the missing light for the rest of the night. A postshow summons to Siegfried’s chambers was the worst possible way for an employee to end the evening. He would sit in his chair, dripping with sweat, pulling on a cigarette. “Tell me why this happened,” he would say. “And then tell me why it will never happen again.”

There are no bad elephants, but some elephants are easier to handle than others. When Siegfried & Roy moved to the Frontier, they acquired Gildah, an excellent elephant. She was the heart of what was then a new old trick: making an elephant disappear. Houdini did that in 1918. No magician had attempted it since, mostly because no magician happened to have an elephant handy, or a performance space big enough to vanish one. Teller, of Penn & Teller—two more magicians who call Las Vegas home—is the Siegfried of his particular duo: the logician, the focus, the sober second thought. Making an elephant disappear, Teller says, “is the kind of thing that you read in a magic book and you say, ‘Well, that’s a clever idea, but no one could actually do that.’ And they did, which is perfectly consistent with everything about their thinking: Take whatever it is, and do it over the top.” Siegfried was a devoted student of magic, but he was never much of an inventor. Siegfried & Roy knew that they would be forgiven for their unoriginal illusions so long as they elevated them, and giant animals have a way of elevating everything. The devil’s half of the bargain was that Siegfried & Roy could become the grandest version of themselves only by surrounding themselves with the instruments of their potential destruction.

By the mid-’90s, they had an incredible menagerie of big cats as well as countless other exotic pets: pythons, alpacas, swans, horses, goats, and a turkey named Merlin. Some lived at the Jungle Palace or Little Bavaria, but after the Secret Garden was built, in 1996, the cats were usually kept there.

The compound also became home to a fiercely loyal woman named Melody Hitzhusen. She spent her youth with the elephants and other animals at Ringling Bros. before Siegfried & Roy lured her away from one circus to another with the promise of magic, cats, and a little bungalow-style apartment among the animal enclosures. Today, a black leopard prowls outside her kitchen. A lion sleeps on the other side of her bedroom wall. When it roars, her windows shake.

By the time Hitzhusen arrived, Roy—she called him Mr. Roy—was almost always in the company of tigers. Siegfried was never much for the animals, seeing them as a means to an end: “They were props,” Hitzhusen says. (The dolphins were Wynn’s contribution and never part of the act. Legally blind, he often took his lunch next to the Secret Garden’s dolphin pool, luxuriating in the good dolphin vibes.) After the cheetah and the leopard, Roy’s next cat had been a lion he’d somehow obtained from Puerto Rico, where he and Siegfried would vacation for several weeks a year. Lions, he found, never really lose their predatory instinct. Lions want to hunt, and that makes them nervy pets. “We’re setting up ourselves not to succeed if we try to move a lion around multiple times a day” is Hitzhusen’s way of putting it. Tigers are far more eager to please.

Siegfried & Roy’s streak—one collective noun for a group of tigers; another is ambush—began in 1983 with the acquisition of three white cubs, imported from India via the Cincinnati Zoo. What Roy called his “family” grew from there. There were soon dozens of tigers at the Secret Garden, many of them white.

Roy often claimed that white tigers were a distinct subspecies of tiger. That was a lie, covering up an unpleasant truth. Every white tiger in the United States is believed to be the descendant of one white male Bengal tiger captured in the wild in India as a cub, a genetic anomaly named Mohan. He was bred with his daughter to produce more white tigers, and his deviant blood still courses through the veins of many of the cats today. Most white tigers look regal (there are incestuous exceptions), and they seem like they could possess divine powers, the way white moose are regarded by some First Nations people in Canada as sacred, as spirits watching over them. But white tigers are not, in fact, mystical. They’re mutants. They’re beautiful freaks.

They are also tigers, and so they possess the attributes universal to all tigers. They can cover more than 20 feet in a single leap. In captivity, they consume seven to 12 pounds of raw flesh each day, and they can weigh as much as 660 pounds. They smell of urine and pheromones. They signal displeasure or impending malice with raised ears, stretched-out whiskers, and dilated pupils. Tigers are capable of exerting a bite force of more than 1,000 pounds per square inch, and their four canine teeth can be up to three inches long, the largest of any predator. All tigers eat nothing but meat.

By far Siegfried & Roy’s most amazing trick was making everyone forget that they and their audiences of A-list celebrities, former presidents, and ordinary tourists were in proximity to unchained animals that are widely feared for their capacity to kill. Steve Wynn was a notable exception. “I was afraid,” he says. Before the show opened, he did a photo shoot with Siegfried & Roy and a tiger. Siegfried didn’t know that Wynn spoke some German, and so also didn’t know that Wynn understood when he told Roy to keep his hand between the tiger and their patron, “just in case.” That memory stuck. Night after night, year after year, 1,500 people at a time sat next to a parade of inveterate carnivores with claws and sharp teeth. Wynn’s theater was a small-scale version of Jurassic Park.

There was almost always a moment during the show when Roy entered a cage and, with the aid of a purple curtain and some hidden doors, was “turned into” a lion, and that lion almost always took a swipe at Siegfried, who theatrically evaded its claws. Once, Siegfried failed to escape the clutches of a lion that went off-script and bit his arm. He needed several dozen stitches to close the wound. To the paying customers, the lion’s reach seemed like a moment of genuine risk, and Siegfried’s scar proved that in some ways it was. “As an audience member, you’re drawn into this,” Lance Burton, a former Las Vegas magician, says. “Because you don’t know if this is part of the act or if this is the night the lion’s going to get him.” That moment of manufactured risk also somehow magically obscured the actual risk to everyone involved, the way we get a thrill out of riding a roller coaster when the drive to the amusement park is far more likely to kill us.

Even Teller, normally a truth-seer, fell for Siegfried & Roy’s illusion of audience safety, at least in the moment. “I just remember Siegfried calmly turning to a tiger and pointing to us and saying ‘Eat them,’ ” Teller says. The joke was a customary one—a carefully planned moment designed to seem spontaneous and special—and everyone dutifully laughed, including Teller. “I was actually brought into the make-believe, that somehow these animals were magically humanized,” he says. “In retrospect, that might not have been such a smart thing to do.”

To this day, nearly everyone in Siegfried & Roy’s former orbit uses the same ambiguous noun when discussing Roy’s fateful encounter with one of his animals: They call it “the accident.” On the evening of October 3, 2003, Roy was bitten in the neck by a white tiger named Mantecore. He never fully recovered from his wounds or the related stroke and subsequent cardiac arrests. Those facts are a matter of universal agreement. From there, the truth is the subject of considerable dispute.

Most nights, Siegfried & Roy each covered five miles during the course of a single show, because sometimes what looks like teleportation is just someone running really fast through a tunnel. The rest of the evening was spent hurtling through a series of weird, unrelated vignettes. At one point during the performance, Siegfried & Roy’s colossal mechanical dragon seemed to crush their heads in its talons, only for our heroes to come back to life and conquer it, fighting fire with fire so hot, audience members could feel it on their cheeks.

The mauling happened during a part of the show called “The Rapport,” a quiet interlude designed to allow everyone involved a chance to catch their breath. Roy would walk a white tiger into a spotlight on the stage and introduce the cat to the audience. That night, Roy told the crowd that it was Mantecore’s first time onstage. “Siegfried & Roy always wanted anyone in the audience to feel like they’d come on this very special night,” Chappell says. Mantecore was seven years old and had performed “The Rapport” more than 2,000 times.

During those previous 2,000-plus encounters, Roy walked Mantecore in a circle, stopped, got down on the floor, put a microphone to the cat’s mouth, and asked him to talk. The tiger let out a low growl. Then Roy returned to his feet, and the tiger rose to rest his front paws on Roy’s shoulders. Mantecore was about seven feet tall and 400 pounds, dwarfing the diminutive Roy, despite his wearing boot heels and lifts designed to make him look inches taller than he was. The man and the tiger danced across the stage, always receiving a wave of applause before exiting to the left. It looked as though Roy and Mantecore shared something like love, and on certain nights, the effect could move members of the audience to tears.

It’s not unusual for people with an extreme devotion to animals to believe that the objects of their affection are equally devoted to them. Animal obsessives routinely portray themselves as martyrs, holy warriors who fight the good and solitary fight on behalf of animals, their shared enemies the billions of stupid, thoughtless humans who can’t know what they know. These same people often claim special powers: that they can commune with animals, talk to them in their own private language. Roy had speakers installed in the kennels so that when he went on vacation, he could call and talk to his cats. He claimed that he spoke to them in huffs and purrs.

“When you see a 600-pound tiger, and you call his name from across the way and he comes up to you, that’s magic,” Chappell says.

Roy no doubt was more at ease with large cats than just about any other human being in history. He had spent so much time with them. Roy was present for every birth—his face was the first thing they saw, his voice the first sound they heard—and each animal was conditioned to live a hugely unnatural life from that moment forward. When cubs were three weeks old, Roy introduced them to the lights and noise of the theater, picking them up out of a basket and cradling them in his arms, allowing members of the audience to pet their soft fur. Those same cubs grew up to lounge around like gigantic house cats, roaming the properties freely, sleeping in beds, swimming in the pool, performing tricks for audiences, and receiving treats for obedience.

Roy even rode them like horses. It was as though they’d been bred twice: once to be white, and again to become something other than what they were meant to be.

Roy, several of his employees, and even some members of the audience knew something was amiss from the start of “The Rapport.” Mantecore seemed confused and out of sorts, missing a mark just seconds into the act. Some witnesses thought Roy was also a little off, perhaps tired from the previous night’s celebration of his 59th birthday, perhaps ill. (“He was not right,” Hitzhusen says.) Siegfried & Roy routinely showed signs of fatigue—for a time, Siegfried handled the stress of the show with too much Valium—and both had started murmuring about winding things down. But it’s almost impossible to write the ending to a fairy tale you’re living, especially when it employs 250 of your most devoted friends. Siegfried in particular wasn’t sure what he’d do with himself after. He hadn’t thought of living any other kind of life.

“What is wrong?” Roy asked Mantecore out loud. He tried to correct the tiger’s position on the stage. In 2019, Chris Lawrence, one of the animal handlers standing in the wings that night, told The Hollywood Reporter that Roy had made a handling error. Rather than walking Mantecore in a circle to coax the tiger into position, Roy tried to steer him with his arm, essentially shoving him. The tiger’s ears perked up, and his whiskers grew longer. Lawrence said Mantecore’s eyes turned a warning shade of green. Roy sensed the danger too, but before he could act, Mantecore nipped at his hand.

“No,” Roy scolded, and he bopped the tiger with his microphone. Because the microphone was on, the sound echoed around the theater, which had gone pin-drop silent. Lawrence, who had been reluctant to go onstage—spoiling the illusion that Roy alone controlled the animals with his special powers—now felt compelled to intervene, trying to distract the tiger with soothing pats and cubes of steak. But Mantecore remained fixated on Roy. The huge cat swiped at the tiny man, knocking him off his high-heeled feet, and sinking his teeth into Roy’s neck. Blood spurted from the puncture wounds, but Roy could still push out enough air to scream, witnesses said, when he was dragged by the tiger to their usual exit, stage left. Someone sprayed Mantecore with a fire extinguisher, and the animal finally released Roy’s limp body before handlers corralled the tiger into a cage, where he began looking for the dinner he normally received after a performance.

Chappell and Hitzhusen each took one of Roy’s hands as he was loaded into an ambulance. Beyond noting that, Chappell won’t talk about the incident in any detail. “I’m not going there,” she says. After the curtains came down, some members of the audience prayed. Some thought the episode was part of the act and waited for the reveal. Some wandered out of the theater to the casino floor and cried among the slot machines.

Surgeons saved Roy’s life, stopping the bleeding and opening his airway, but he flatlined three times and suffered brain damage. He spent the next few months in the hospital, and the next few years relearning how to walk, talk, and swallow. After the incident, Lawrence was beset by terrifying nightmares in which his throat would get ripped out, and most of the employees were told that they needed to find other work. Siegfried & Roy rarely appeared in public together again, and performed onstage only once, briefly, in a charity show at the Bellagio in 2009.

Because of belated public-safety concerns and persistent rumors of sabotage or foul play, the U.S. Department of Agriculture embarked on an exhaustive exploration of the incident, eventually releasing a 233-page report. The chief investigator nosed through some vaguely conspiratorial-seeming explanations—that someone “had intentionally and maliciously distracted Mantecore”; that he had been put off by the “beehive hairdo” of one patron; that someone had released a scent that caused the tiger to sneeze and become ruffled—before ultimately finding only that the tiger had not been under “direct control” and that in the future, it would be a good idea to keep barricades between large cats and humans.

Upon reflection, it’s an incredible testament to Siegfried & Roy’s capacity for illusion that there was so much debate about what happened that the USDA felt the need to write a 233-page report. In 2014, Siegfried & Roy appeared on Entertainment Tonight, ready to announce the “real” explanation. The clip is on YouTube with the title “Roy Horn Reveals Shocking Info on Tiger Attack From 11 Years Ago.” Roy, the same man who’d once claimed that his pet wolf-dog had rescued him from quicksand, told his gullible-seeming interviewer that he’d passed out onstage following a naturally occurring stroke, and the worried tiger, sensing the problem, gently took hold of his neck and, like a mother ferrying a cub, delivered Roy offstage to help. The accidental bite and loss of blood, Roy said, relieved the pressure building in his brain, saving his life. “It was an absolute blessing,” he said. Adding to the beauty of it all, Roy wrote on Facebook, Mantecore had nearly died soon after his birth and Roy had revived the cub by breathing air into his lungs. The tiger was only returning the favor. “I saved his life and then he saved mine,” Roy wrote.

Hitzhusen believes that the stroke did in fact happen before the attack, which would explain why Roy “wasn’t right.” Asked whether she believes that Mantecore became the first tiger in history to save a human life, she shrugs. Most of the commenters on the Entertainment Tonight video saw Roy’s tale for what it was—the most transparent illusion of his career—but not all. “What a sweet baby,” one comment reads, referring to the tiger. “He tried to help him.”

Magic and grief both have the capacity to expand our imagination. Both send us searching for explanations. Early in 2020, Roy caught a terrifying new virus. He was 75 years old when he was diagnosed with COVID‑19. Siegfried went to the hospital and watched through glass as his partner’s chest rose and fell to the rhythm dictated by machines. He swore that Roy knew he was there and that Roy moved his hand, as though to wave, and a tear ran down his cheek. Because of the way the two men had always communicated with only a look, Siegfried believed that he and Roy said goodbye in that moment, finally and properly. Who knows? Only they could say, and now neither of them is here. Siegfried’s pancreas was already filling with cancer. He died in January 2021, at 81.

The fact that their lives were so saturated with secrets, that the two men were so intentionally unknowable, added a mystique to Siegfried & Roy. But it never felt that way to Sharon Heptner, who was Siegfried & Roy’s personal assistant for decades, even before they arrived at the Mirage. “I love them both very much,” she says, unable to speak of them in anything but the present tense.

On a tour of the Jungle Palace, she walks past the empty glass enclosures that used to hold lions and tigers. She also points to where Siegfried sometimes asked her to lie for long stretches, directing her to move a hand here or a leg there while he stared at her and rubbed his chin. “You knew he was coming up with how he could put a body into something,” she says, without elaborating. She’s naturally cautious, reserved, and discreet, but like nearly all of Siegfried & Roy’s employees, she also signed an NDA that she still abides by: Most of her secrets, and so Siegfried & Roy’s secrets, will stay secrets. “This is Roy’s room,” she says, standing in front of a closed door on the second floor. “You can’t go in there.”

Their wills requested that their assets help fund their SARMOTI Foundation, dedicated to endangered-animal protection and conservation. Before an estate sale was held, certain employees had first choice of inheritances; Hitzhusen now sleeps in Siegfried’s wooden bed. The trustees selected Bonhams, the venerable auction house, to dispose of the rest, and an elegant Englishwoman named Helen Hall arrived to take stock. Any piece of magic that betrayed a trade secret was off-limits. Nearly everything else was fair game. Hall chose 482 items and had them boxed up and shipped to Los Angeles. Hitzhusen hasn’t had the heart to go into either of Siegfried & Roy’s former houses since. Like Siegfried and his eye for absent lights, she’s worried she’ll see only what’s missing.

In the sprawling collection of art, costumes, and jewelry, it wasn’t difficult to divine which of the pieces Roy had bought for Siegfried and which he had bought for himself. (Roy was the shopper.) Anything of Asian or Middle Eastern origin—such as the “carved amethyst figure of a seated Buddha” that sold for $637.50 and the “Indo-Tabriz style rug” that went for $1,211.25—was Roy’s. Siegfried’s spirit could be better found in the massive “European Gothic style carved wood pulpit” that brought $1,657.50. (He remained devoutly Catholic his entire life; his younger sister is a nun.) The “Versace three-piece porcelain smoking set” ($1,530) was also Siegfried’s, in which he extinguished his postshow cigarettes and however many clumsy careers.

Through it all, the room behind the locked door, the one that Heptner won’t open for guests, remained sacred and untouched. Inside, there are shelves of urns, each one containing the ashes of a departed animal. Only Gildah, the excellent elephant, was buried in the yard at Little Bavaria, because no crematorium could contain her. (A thousand years from now, someone might dig up her enormous bones and have to reconcile some things.) To this day, the ashes of every lion, every leopard, every tiger that dies in the Secret Garden are brought back to the Jungle Palace and placed next to Roy’s vacant bedside. Hitzhusen vowed to Roy that she would stay until there were no animals left, and she is the sort of person who keeps a promise. She has 14 urns left to fill, and then she’s going to move to an island in the Pacific Northwest and listen to the rain.

Like their animals, Siegfried & Roy were cremated, but the location of their ashes is one last secret. Hitzhusen will say only that their final resting place is in Nevada, and they are together again.

In their waning years, Roy had stayed mostly out of sight. Siegfried missed having an audience. He tried to occupy himself by learning to do the things that “normal” people do but he never had, like pumping gas and grocery shopping. He was mesmerized by the magic of ordinary life. But nothing really did the trick until Siegfried began returning to the Secret Garden virtually every day.

There, under the shade of the palm trees, he drifted through the ebbing crowds, waiting for someone to recognize him. He always feigned surprise when they did, careful to make even his smallest audiences feel special. He told them that he was rarely there anymore, that their meeting must have been fate. Siegfried then took out one of the gold coins that waited in his pocket. He had thousands of them made: Look for the magic that is all around you, they read on one side. Then he performed a little magic—close-up magic, quiet and simple, the way he once did, before everything else.

Surrounded by the cats who reminded him so much of his lost partner—the same animals whose hulking presence had helped turn their first day together and every day after into the most extraordinary existence for everyone in their sprawling, magical family—Siegfried heard time and again the same five words his father once said to him: “How did you do that?” He never answered. Instead, Siegfried would smile, press the coin into the hands of one of his guests, and float away, leaving his visitors to stare at one another in silence, and the last of Roy’s tigers to exalt in their wonder.

This article appears in the November 2022 print edition with the headline “The Original Tiger Kings.”