Mike Conner sits in his truck atop a hill in Boring, Oregon, where he can feel the summer breeze through the window and see the sun at its meridian over the fields and the snowcapped tip of a distant Mount Hood poking into a cloud-dotted sky. He sits here and thinks about cutting off his feet.

His legs are barely his anymore—just fused cadaver bone and metal. Nearly half of six-foot-four, 225-pound Mike is steel and titanium: the majority of his legs from his knees down, his shoulder, his elbow, his wrist, his back, and his spine.

The Pain comes from his feet.

It starts in his soles and his mangled toes, which are missing knuckles. It surges up his ankles, which he can barely flex—they’re just bone on bone, no joints, no cushion—up his atrophied legs, where the bones still have holes in them and where one is shaped like an S. It climbs his rebuilt spinal cord, up past a small stimulator fitted near the vertebrae and designed to reduce pain signals that find his brain. They shoot up his legs and spine and, when the battery gets low, find his brain anyway. The Pain: a five-hundred-pound sack of sand on his back, his feet in a bear trap.

“AGHHH!” He stretches his metal feet beside the gas pedal.

Every day, it’s just Mike and the Pain. When he goes to sleep, when he wakes, when he sits up in bed, when he goes to piss, it’s just the two of them: Mike and the Pain. He keeps slippers by the bed, because walking barefoot is like walking on shards of glass.

“AGHHH!” He arches his half-locked ankle.

He has to keep stretching or everything will get stiff and then nothing will work and then everything will hurt worse. Or he’ll need more surgeries. (His most recent was his thirtieth, because his toes were turning into claws and wrapping beneath his feet.) Or maybe he could stop having surgeries, and possibly stop the Pain altogether, and just cut off his feet. He thinks about it every day. He’s thinking about it right now.

But he doesn’t want to do it. Mike doesn’t want to cut off his feet for the same reason he doesn’t want to kill himself. It’s a long story. And he has a long drive ahead.

Part I. Surviving

In the life that came before the pain, Mike was an engineer. On April 2, 2013 he was working at Northside Church in Clovis, California, checking sprinklers the fire marshal said were no good. The job was four flights up, in the attic, with nothing but steel beams and a catwalk suspended over the altar. He brought a flashlight.

Up there Mike Conner climbed with some other engineers. He was the last one to walk the beams; the other flashlight rays ahead of him were the only things he could see. “I’m going to the catwalk!” Mike called. He went to step across the beam, and as he stepped, a ray of light swiveled his way—by accident or to light his path, he will never know—and caught his eyes instead. Midstep, for a second, Mike Conner went blind. He stepped anyway.

And then he fell.

He could hear himself scream. He dropped through the beams; the altar—which had been cleared for construction, nothing but concrete—rushed up at him.

His feet hit first.

And then everything exploded.

His feet exploded inside his shoes. His tibias and fibulas exploded like shrapnel through his slacks. His knees went in different directions. Then his butt hit and that exploded, too. Then his spine: Four of his vertebrae blew out and every rib, front and back, cracked. And then he fell to his right side and broke everything there: the bones in his hand, the bones in his wrist, the bones in his elbow and his arm and his shoulder—all destroyed.

He could hear others scream and then the sound of heels—clomp clomp clomp clomp—and a woman’s voice—“Call 9-1-1!”—and then, as the clomp clomp clomp came nearer and the voice got louder, he heard a gasp: “Oh my . . .” Then creation went black.

And then, suddenly, Mike Conner found himself standing before a large wooden door, like in a castle. Tall, dark, beautiful old wood. He could feel a protective arm move across him, opening the door with a creak, and inside there was blackness. Then Mike heard a voice, epicene, monotone, beside him in the dark. The voice asked, “Do you want to live?”

Mike had a question, too. “Does my penis work?”

And then he awoke. The footsteps drew nearer. He contracted his stomach. He felt his balls and penis move and Mike knew his answer.

He drives up the interstate 5, where the evergreens divide the highway and clouds roll over distant hills. He uses cruise control, mostly. His foot is so heavy with metal he often speeds. Earlier, a cop didn’t believe Mike when he told him this. Mike got a ticket.

He gets out at a truck stop to pee. He walks, limping slightly, across the lot. He limps because the calcium that formed between the bone breaks made them grow unevenly: an inch on one side and three quarters of an inch on the other, and now his legs aren’t the same length. He wears shoe inserts. He limps into the bathroom, where a man in a wheelchair is brushing his teeth in front of the mirror.

“Hey, man, what put you in the chair?” Mike wants to know. No one asks that question, but it’s likely the only thing the man thinks about.

“I was in a bad car accident,” the man says.

“Dude, I fell five stories,” Mike replies.

He towers over the man. He is covered in tattoos that tell the story of the fall—a skull and a hammer and sword. His voice is surprisingly high.

“I just got out of the chair four years ago,” he says.

He shows the man his reassembled hand, which is still crooked on his wrist and with which he can only perform a knock-knock motion, and his knee, which points inward 10 degrees, and his shin, which points in 12, and his elbow and his shoulder, both of which have been rebuilt.

The man looks up at Mike: “You were in a wheelchair?”

“It can be done,” Mike says.

He tells the man about therapy machines, about the towel thing he does in the bathroom every week—throwing it out in front and then bringing it back with his toe claws—and the man pulls out his phone and starts typing notes.

Mike cheers him on. “Fuck yeah, dude, you kill it! You go to bed tired! You go to bed with a frown on your face because you’re so tired! Because you have no other choice! Just push it! Your blood, your sweat, your tears, everything, your motivation, anything that drives you—use it to work your ass off!”

“Wow, thanks . . .” the man says.

Mike pees and leaves the bathroom, limping slightly.

Part II. Sitting

“I’m sorry, Mike.” A human voice issued forth faintly, the first sound Mike remembers hearing, as his pulverized body was wheeled into surgery. “Your spinal cord is shredded,” the voice said. “When we open you up, the pressure might snap it.” It’s Mike’s memory that the voice said: “You are probably going to die.”

Surgery. Eighteen hours passed. More voices. Images. They emerged darkly. A guard tower. Movement in the shadows of the ramparts. They were calling names of soldiers and passing in front of him. The bars of a cage. How Mike was captured and put into this camp, he could not remember. Only boarding an LST at Thirty-second Street in San Diego. The years at sea, the best years of Mike’s young life: on the bridge with the captain, the sunsets, orcas swimming alongside the ship, Australia, Japan, Korea, towing minesweepers across the Pacific, thirty days without land, Hormuz, the .50-cals firing back into the hazy brush, the oil fires.

The shapes changed. The guard tower: a nurses’ station. The voices: doctors. The bars: a curtain. More voices: his children.

Mike awoke.

He was lying in bed, his legs stretched out before him, locked in place, his right arm clasped over his head. A doctor came in to tell Mike what happened. The good news first: He was alive.

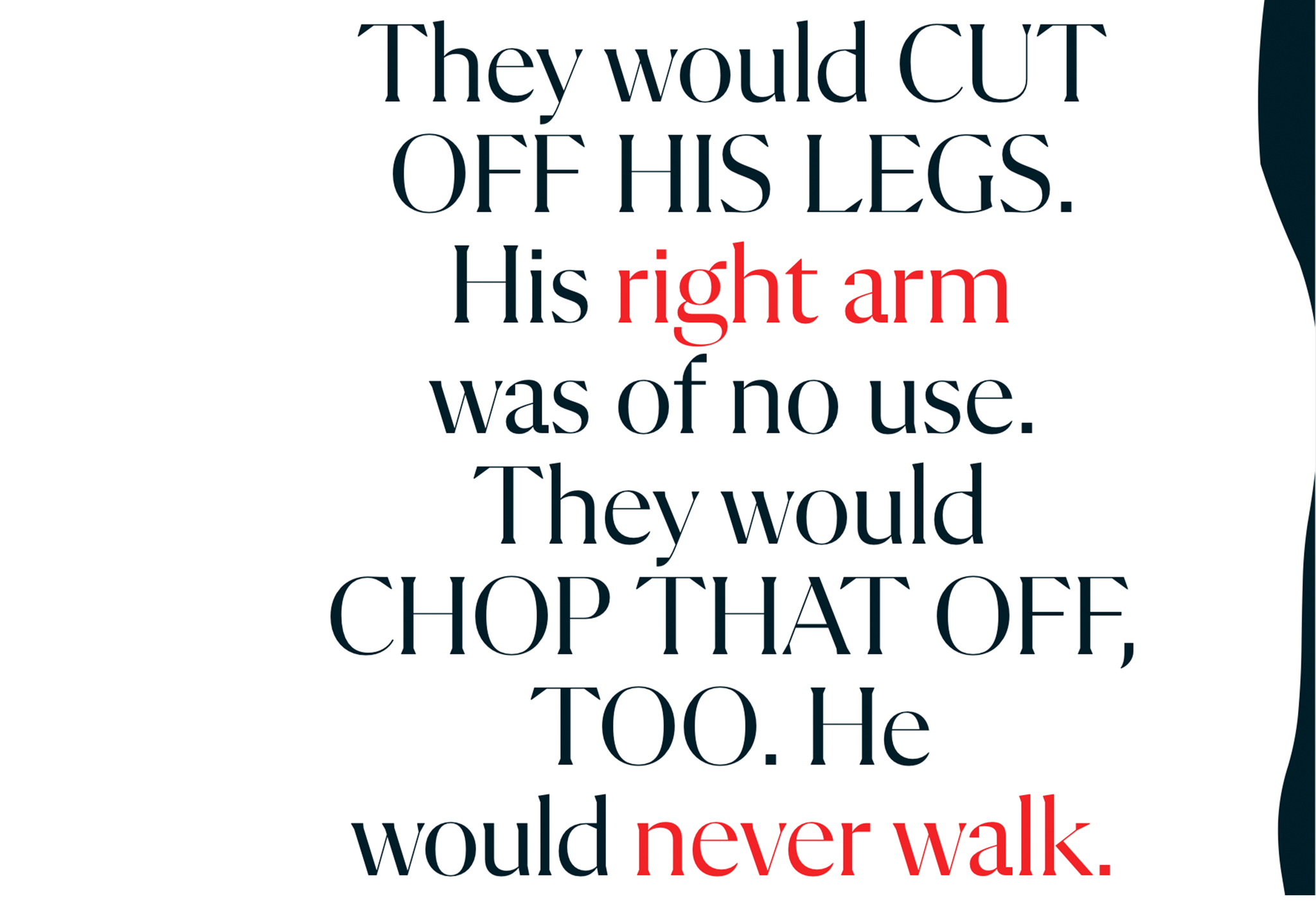

And then the bad news: He was going to lose everything.

They would cut off his right leg. They would cut off his left. His right arm was of no use; it would just hang there like a lobster claw. They would chop that off, too. Mike would become just a torso and an arm. He would never walk. He would never stand. He saw the despair in his wife’s eyes, and he knew that someday she would leave him.

He lay there for weeks.

When he shifted at night, he could feel his back bones move and his ribs shift, too, as if floating in liquid. Nurses came each morning to tend to his legs. They straightened his leg bones by hand. The bones were nothing but mush.

He made a plan: If he could move it, he would work it. He would start with the thumb and forefinger on his left hand. Thumb to forefinger to middle finger to ring to pinkie. Repeat. He would imagine his claw arm doing the same, even though it could not. Then he would do Kegels so that he could feel his balls move and know that he was still a man.

After a time, they sent him upstairs. On the rehab floor, he learned to sit. They put a wood plank at the edge of his bed across from his electric wheelchair and he learned to move across it, sliding on his butt. It was like sitting on a swing, his useless legs out in front, his fragile spine in a cage, his whole body sweating with fear, the hospital tile beneath like the rocks at the bottom of a canyon.

He took rides in his wheelchair, steering with only his good fingers, to the end of the hall. There, one day, he saw them.

The paraplegics.

They were strapped to beds upside down, their families lying on the floor below them, talking to them, wiping drool off their faces. The drool would occasionally drip to the floor.

I am the lucky one, thought one-armed Mike Conner, butt-walking onto his wheelchair, his useless legs dangling over the tile.

He drives down across the Oregon border, through the shadow of Mount Shasta, where forests turn to deserts, then back into forests. It’s a twelve-hour ride between his home in Clovis, seventy-some miles from Yosemite and the sequoias, and his plants in Boring. He is not an engineer anymore. He grows cannabis legally. He owes his life, he believes, to the plant. The season’s harvest has just begun—the branches broken down, the buds trimmed.

When he takes this highway north into Washington to visit his brother, when he sees Mount St. Helens, he remembers.

He was fifteen, the year after the volcano erupted. He met his father for the first time. His father left when Mike was born, and a sailor took his father’s place and moved the family to California, where he loved the sea more than he loved Mike. He met his birth father the next year, but it was too late for them. His mother soon left, and then his stepfather left, too, out to sea for good. And then Mike was sixteen and alone, aside from two siblings to feed and speak for at parent-teacher conferences. That’s why Mike isn’t wired to complain. Life, in his experience, has rarely been anything other than meeting the needs directly before him.

Part III. Standing

After eight weeks, the last hospital day, when the insurance company was no longer willing to pay, Mike came home to a six-bedroom house, four teenage kids, and the wife he knew would one day leave him. They set him up in the den, wheeling him beneath the small archway off the kitchen. His legs were locked in front and he couldn’t turn corners; he would never reach his bedroom. Propped up, facing a tall window through which he could see the park across the street and the children climbing structures and the dads mowing lawns and the cat running along the sill—there, in that room, Mike would lie for the next two years.

The first two months were just noise.

The refrigerator had sprung a leak and black mold had grown on the walls, and so all Mike heard was workers demolishing the kitchen and ventilation machines blowing shit all damn day and night.

He could move only from the bed to the commode, a portable toilet his wife had lined with litter-box bags. His kids came to empty it. They would come in, walking past the bed and the triangle overhead for sitting up and the hook used for getting dressed and the rolling table beside the bed with the meds, the oxycodone, the drugs Mike had been taking every hour since the fall, past the two chairs for guests and the TV to help him sleep and the machines from the insurance company to help him exercise; his kids would come into the room and step past these things and collect Mike’s poop. Pick it up in a bag. Take it out to the trash. He felt like a fucking failure.

He watched the kids playing out the window and the other dads doing yard work. He fantasized about mowing his lawn.

Instead, he read. Mostly science books. About volcanoes, eruptions, plate tectonics, the formation of the Rockies, the Himalayas, the majesty of nature. He thought about his wife, who was home less and less, and where she might be. He dreamed, always of falling. He would be on a cliff over a deep canyon, and the cliff would collapse. He would be on a sidewalk, and the sidewalk would crumble beneath him. After each dream, he would wake sweating and screaming.

He watched a lot of TV. He watched a segment where a man in a wheelchair couldn’t lift his kids.

In the dark with the TV on and the future staring at him, Mike thought about killing himself.

How could he put his family through this? How could he let the kids come in and pick up his kitty-litter poop? He couldn’t even shit like a normal human. He couldn’t take a shower like one. What was he doing? He was high on opioids and watching court TV.

He visited the hospital when he felt this way and wheeled up to the sixth floor, where the guys were strapped to their beds and turned upside down to face their families. They were probably telling their wives they loved them, be happy, go on without me, find someone else.

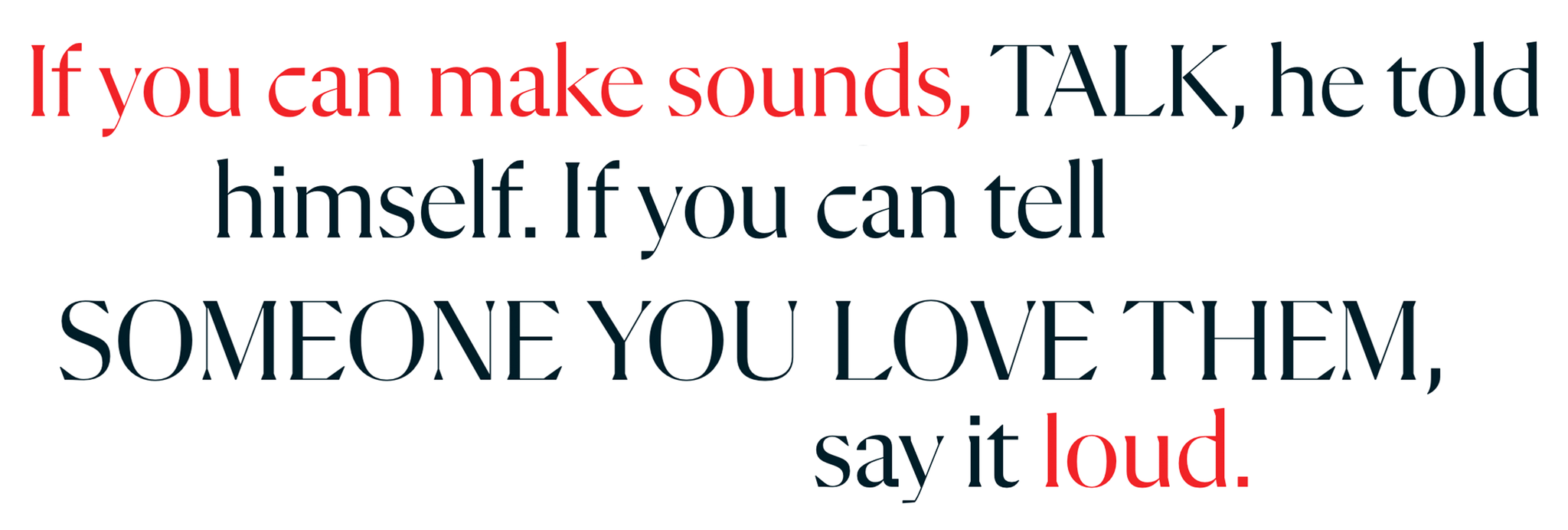

Appreciate what you have left, Mike told himself. Appreciate the breeze and the trees and the birds and the arm that you can move. If you can move, move. If you can make sounds, talk. If you can tell someone you love them, say it loud.

After, for five days a week, he’d get picked up and loaded onto a van and go to physical therapy. The doctors still said there was no way he would ever walk. And so even after the van wheeled him back home, Mike wouldn’t stop. He moved until he was so tired he’d fall asleep with a frown on his face. Every day for two years.

And then one day in rehab, he grabbed hold of a bar in front of him and slowly pulled himself up from his wheelchair. He cried. For the first time in two years, his legs bore weight. He could stand.

Part IV. Walking

His wife left him. It had been more than four years since the fall, and she had stayed, she said, for him. But her world was not a single room with a window, and it hadn’t stopped: She started hiking, which she’d never done, which felt to Mike like a suitcase being packed by the door.

“You can go,” he said to her one day. “Be happy, go on without me, find someone else.”

She stood there by his bed and said, “Thank you.” And then she packed and went.

Every year was a trial for Mike, every movement a labor. There were small labors and one very large labor.

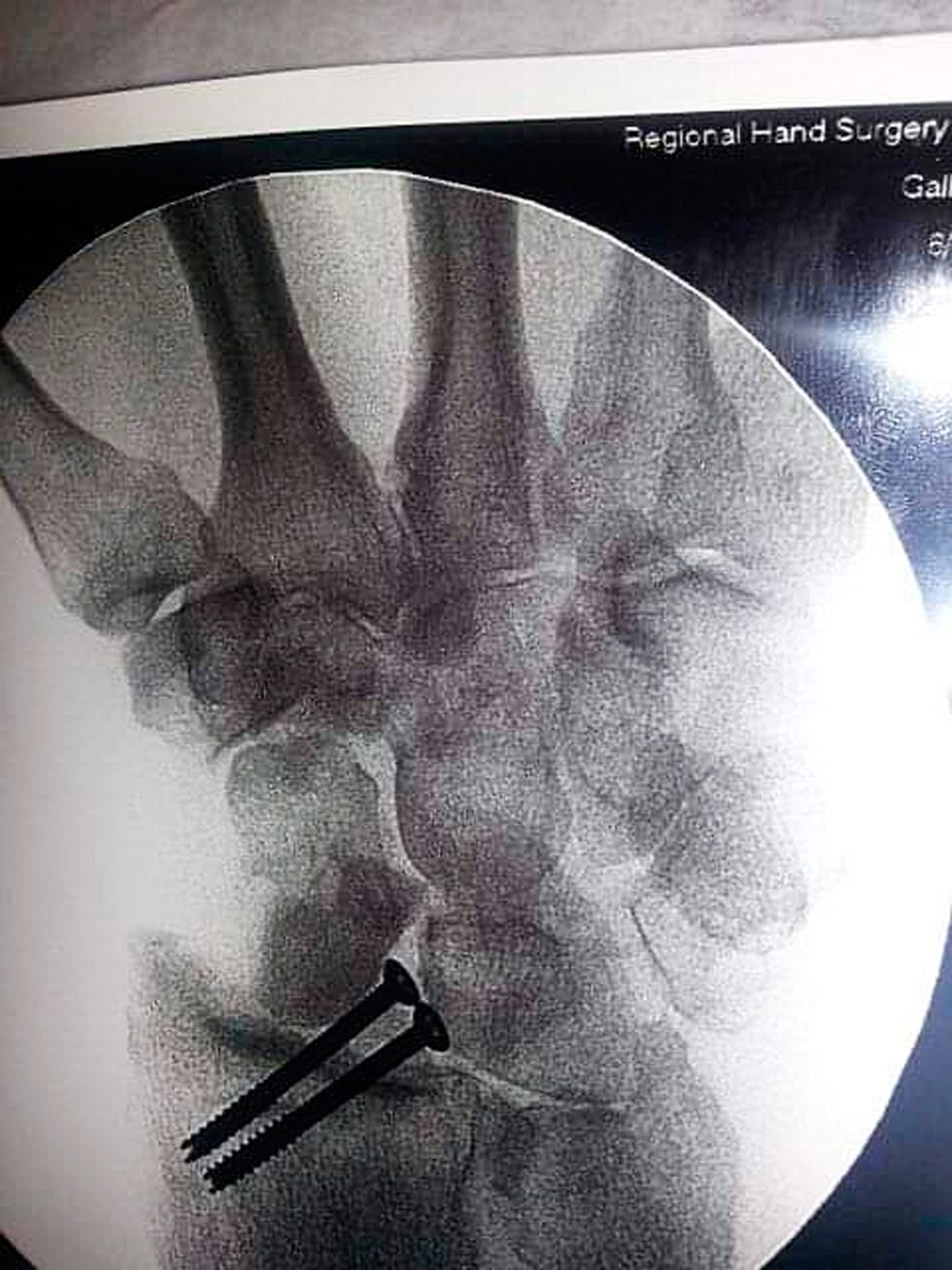

He labored to turn his hand. When they rebuilt it, the hand could barely move. Rotation should be simple: The thumb turns away, the wrist is exposed, and then there is the palm. But Mike couldn’t do it. For three years he hadn’t seen the bottom of his own hand. Upright in bed, watching out the window as the kids played and the dads mowed, Mike squeezed clay. Later, he made jewelry, a necklace for his hand therapist. He told her about his palm, how much he wanted to see it, so one day she put her head down for almost two hours, working his muscles, twisting, pressing, from the elbow to the forearm to the wrist. She told Mike to try. He put all his strength into rotating his hand, turning the thumb outward, exposing the wrist. And then Mike Conner could see it. The palm. He broke down in that therapy office and cried, cried, cried.

This article appeared in the October/November 2022 issue of Esquire

subscribe

He labored to move his ankles. The left one had been locked in place with a metal screw so it wouldn’t drag beneath the wheelchair. Movement should be simple: The toes are pressed to the floor, the foot elongates, the ankle arches. Mike couldn’t do this. He needed his ankles free. He needed new knees, too, so that he could do the final thing he wanted, the very large labor they said he would never do: He wanted to walk.

He demanded that they take the fucking screw out of his foot. The surgery was approved. Then it happened with a pop: Mike could arch his foot.

By Christmas, he could walk again. He took his first steps like a penguin, six inches by six inches, a shuffle. He needed a walker at first, then he learned to stop shuffling, relearned to make strides.

But these trials were nothing, Mike came to learn, nothing compared to the final trial: the Pain.

It never stopped. The oxy didn’t help; it just fucked with Mike’s brain. It started doing other stuff, too, stuff it does when you take 420 mg of it every day, as Mike did. He was talking to his teenage daughter one day when—pop!—he couldn’t hear: Her mouth kept moving but there was no sound. And then—pop!—it came back just that quick.

He hadn’t come this far, hadn’t worked and suffered and yelled at the doctors, only to be a slave to a drug. So one day he put the pills on the bedside table and told his teenage kids to take the guns upstairs, where he couldn’t get to them, because he didn’t want to kill himself and he knew he might try.

He waited for the Pain.

He drives. Sadie sits beside him. Dark hair, dark eyes, tattoos.

He drives. Sadie sits beside him. Dark hair, dark eyes, tattoos.

In the life that came before the Pain, Mike was a natural with girls. He was able-

bodied, tall, with thick blond hair, cool blue eyes. In his new Suzuki Samurai, on his twenty-first birthday, the blonde who pulled up behind him in a Mazda flashed her lights at him: Mike Conner’s first wife. The girl he saw through the shop window, later, when selling radio advertisements: his second wife, the mother of his children. And then right around 9/11, the steady one, the role model to those children: his third wife. The one he told to leave.

But he didn’t know how to do it anymore. He could barely walk when he hobbled into Sadie’s salon. He thought she was too pretty, that she would see him and think, Creep. But he sat and talked with her. He kept coming by, hobbling in, asking for a cut. They talked about her three kids. She liked him, he could tell. She liked that he was a dad. She liked his dumb jokes. She didn’t care that his legs were metal and that he had no knees.

The sun falls gold over the hills. He turns on the radio, finds the country station.

“What are you doing?” she asks.

“Playing country music,” he says.

She laughs.

“But you don’t like country.”

“I don’t know . . .” he says, trailing off.

What he wants to say but doesn’t is that he’s trying to think of others more. He’s trying to yell less. Confront people less. All for her.

Instead he says, “I was just thinking that maybe you would like to hear some country music.”

She takes his right hand. She holds the palm he only recently began to see.

Part V. Living

The pain returned not long after the guns were taken away.

It came with withdrawal, which wasn’t so much a pain as a need that made pain do its bidding. As the sweat budded across Mike Conner’s body, as the body itched and then started to scream, he began seeing things, feeling things, and then he started to scream. They were not real, just a trick of the brain: Bugs crawled beneath his skin; a sharpness spread along his thigh and turned into stabbing; a long, hot knife stuck into his leg, his muscles contracting around it—the knife, the knife, the knife, for hours and hours and hours. And a voice:

Just take the pills, Mike! Just take the pills! Mike! Take the pills!

He thought of himself as a Neanderthal in the cave. A Viking berserker on a ship. Frenetic violence. Wild libido. His body was made to fuck, to fight, to hunt, to gather, to overcome. His body was not made to push a shopping cart down an aisle where food was prehunted, pregathered. It certainly wasn’t made to lie in a fucking hospital bed or take oxy and watch Judge Judy.

He was cutting away milligrams of the oxy every day, barely holding on, when his kids brought him the lemon muffin, saying, “Here, take this, Dad. It will help with the pain.” He ate a quarter and nothing happened. He could feel the sweat, the Pain coming. He ate another quarter and nothing happened and so he ate another quarter and then . . . it happened. He slid onto his wheelchair and rolled over the hardwood into the living room, where his teenagers looked up and saw their dad rolling and crying and wailing: “I’m sorry! I’m such a bad dad!”

They started roaring. They laughed and laughed and laughed and then Mike started laughing, too.

“Dad, calm down,” they said. “You’re high. You’re really, really, really high.”

He was ridiculously high. But the cannabis saved him. And after six months of cutting oxy, he was free.

But there was a cost. The Pain stayed. He resolved then to live with it. It would become an attitude, Mike Conner decided, an emotion, something he could ignore, like rage, like afternoon sadness. It would become his constant companion, and Mike would endure.

Five years had passed since the fall. He moved away from the house with the window facing the playground, down the street to a new place that wasn’t so big or empty, the kids being on their way out now. He met Sadie. He covered his body with tattoos. He bought a cannabis farm.

And on a July afternoon, the breeze coming through the window, the sun over the hills, Mike sits in his truck with the Pain and thinks, for maybe the thousandth time, about cutting off his feet.

But then he remembers.

He remembers falling. He remembers the feeling of an arm hugging him across his chest when his body hit the floor and exploded, locking his arms above his head, protecting him from what was to come. He remembers the hand that covered his face and closed his eyes. He stood before a large wooden door, and the protective arm pressed the door open.

At first all was black. Then, from the threshold, Mike saw everything; every good thing that had ever happened to him, every good thing he had ever done rushed toward him: He is seventeen and it is a beautiful 83 degrees on the bay and Mike is lying on his back in the park. He’s shooting hoops. He’s lifting his firstborn child. He’s with his children, all of them, and they are catching their first fish and showing them off to a smiling Mike. He remembered everything. Every word told to him by every teacher, every sound, every sensation of joy.

The voice wanted to know: “Do you want to live?”

Even with his wheelchair in the garage now, patiently waiting for his older years. Even though he still uses a walker from time to time and some days he’s in so much pain he can barely get out of bed. Even though the Pain abides. Even though it is going to hurt forever. Mike feels his balls and penis move. He knows. The next life is just a space you fill up with this one. Those memories you get to experience, through the door, exist only because you made them. Life is worth sticking around for that. Life is worth filling up.

He sits in his truck in the driveway of his home in Clovis. The drive is over. The neighborhood has gone quiet, the bicycles put down, the kids inside taking refuge from the heat. He makes his way over the threshold of his home, limping slightly.

He lies on his back. The Pain nestles there, too. The signals shooting up his legs. The slippers by the bed. The bear trap. Mike Conner stretches. He stretches his metal feet and arches his ankle and lets out a long grateful sigh: AAGGGGHHH.