Stone Skipping Is a Lost Art. Kurt Steiner Wants the World to Find It.

Meet an amazing man who has dedicated his entire adult life to stone skipping, sacrificing everything to produce world-record throws that defy the laws of physics. To hear him tell it, he has no choice.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

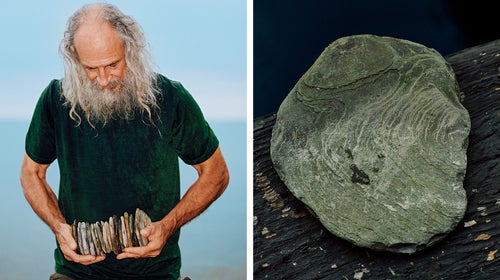

On a clear-skied morning in March, Kurt “Mountain Man” Steiner stood at a lonely bend of Sinnemahoning Creek, deep inside Pennsylvania’s Elk State Forest. He was dressed in a black hoodie and Dollar General jeans that hid his athletic 56-year-old frame, and wore a brown beanie that pressed his long gray hair and Rasputinesque beard into a single wild mane.

Steiner stared across the creek and raised his right arm into an L, clasping a coaster-size sliver of shale the way a guitarist might hold a plectrum during a showstopping solo. But rather than fold his torso horizontally, as you might expect somebody skipping a rock to do, he stretched his five-foot-nine-inch body vertically, and then squeezed down like an accordion and planted his left leg to crack his throwing arm, placing the rock under so much gyroscopic force that it sputtered loudly as it left his hand, like a playing card in a bicycle wheel.

The rock appeared for a brief moment to fly. Then it dipped and plunged, kicked up a wave, rode it like a surfboard, and became airborne again. Standing behind Steiner, I counted at least 20 skips before the rock slowed, scrolled gently right, and sank in the calm water some 50 yards away.

This would have been the greatest throw of my life. To Steiner it was a bullpen toss, and an average one at that. He grunted disapprovingly, then stooped to grab another stone from the small pile he’d gathered from a 25-gallon tub sitting in the bed of his 1989 Toyota truck—one of the quarter-million rocks he estimates he’s thrown in his lifetime. One hour and dozens of stones later, we headed back to Steiner’s tiny, Walden-like home, 30 minutes down back roads and dirt tracks into the bowels of the forest. His shoulder was stiff, and the biggest throwing season of his life loomed. “This could be bad news,” he told me.

Kurt Steiner is the world’s greatest stone skipper. Over the past 22 years, he has won 17 tournaments in the United States and Europe, generating ESPN coverage and a documentary film. In September 2013, he threw a rock that skipped so many times it defied science. This year he hopes to smash records on both sides of the Atlantic, giving him a platform for sermonizing about a sport he believes is nothing short of a means for the redemption of mankind—“a legitimate path to an essential inner balance,” he says.

Skipping has brought Steiner respite from a life of depression and other forms of mental illness. It has also, in part, left him broke, divorced, and, since the death of his greatest rival, adrift from his stone-skipping peers. Now, in middle age, with a growing list of aches and pains, he must contemplate the reality that, in his most truthful moments, he throws rocks not simply because he wants to, but because he has no choice.