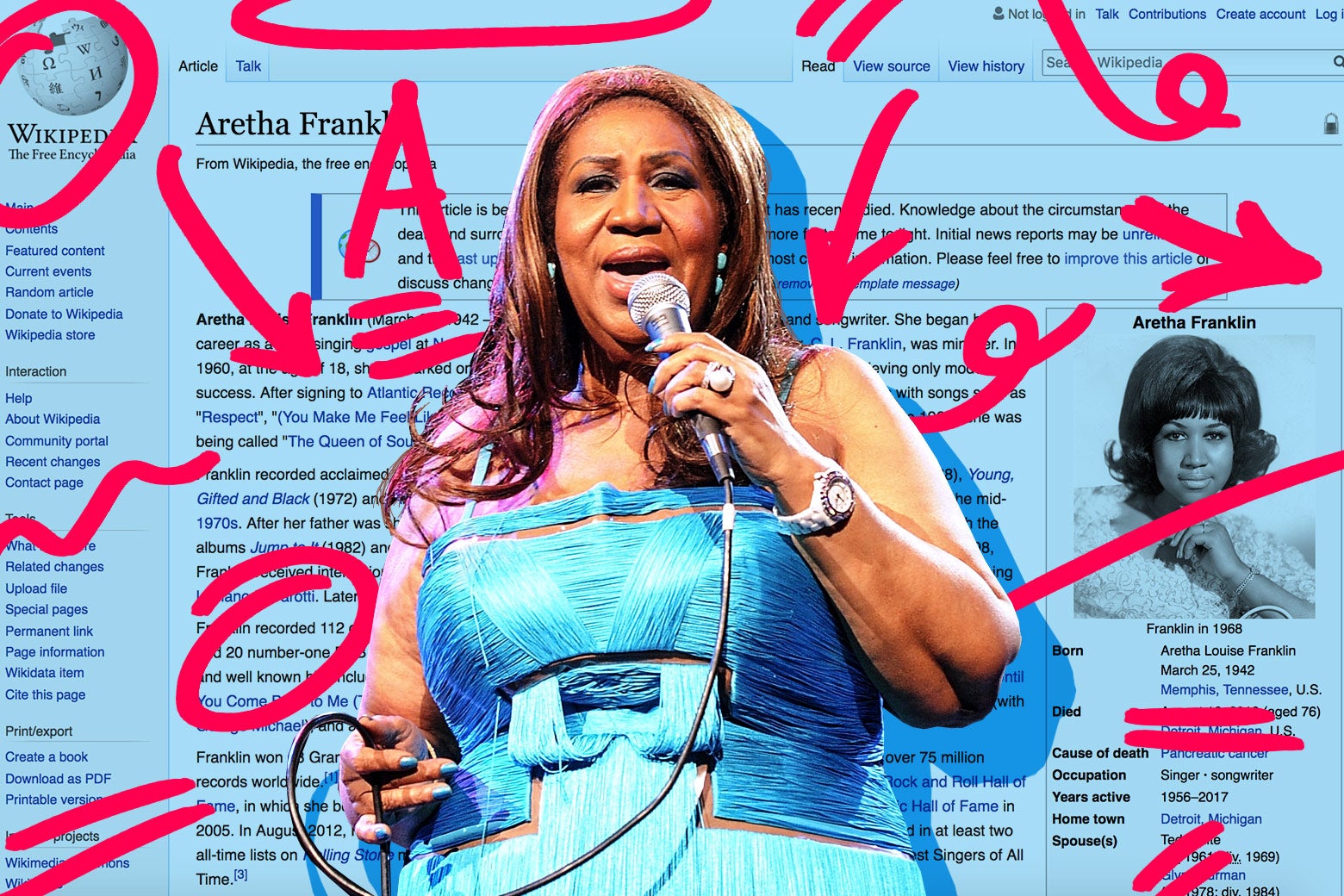

At 9:50 a.m. Eastern time on Thursday, Aretha Franklin’s publicist announced that the Queen of Soul had died from advanced pancreatic cancer. Eleven minutes later, a Wikipedia user named CezarPiotrowski added Aretha Franklin’s Wikipedia page to the category of 2018 deaths. The next minute, Wikipedia user AlexBogue89 used a mobile device to update the first sentence of Franklin’s article with her date of death. Mere seconds later, a third user revised the sentence to past tense, replacing is with was, so that it read: “Aretha Louise Franklin (born March 25, 1942 – died August 16, 2018) was an American singer and songwriter.” These Wikipedia updates would soon be available to Google’s info boxes, Alexa, and Siri, which all source information from the site.

The British hacker-culture newsletter B3ta recently asked its readers a question for the ages: “WHO THE HELL UPDATES CELEB DEATHS ON WIKIPEDIA SO QUICKLY?” After noticing seemingly instantaneous editing this year to the pages for Aretha Franklin, Stephen Hawking, and Anthony Bourdain, I became curious too: What kind of person wants to share this sad news with the world, and did they (perhaps perversely) enjoy it? In darker moments, I thought of the Hunger Games series and its Control Room, where twisted game operators set off a bone-chilling cannon to announce that one of the tributes has fallen. Were the Wikipedians who made these speedy death edits sounding the digital cannon?

Hay Kranen is a Dutch web developer and active volunteer Wikipedian who decided it was worth investigating the identities of these so-called “deaditors.” In a blog post earlier this year, he recounted his process. He began with the 6,700 people with Wikipedia articles who died this year, then narrowed that down to 165 and finally 26 celebrities with articles in multiple language editions of Wikipedia.

When we spoke by phone, Kranen said his research led to three key findings: First, death edits in the sample were made by a highly diverse set of people. More specifically, none of the edits was made by the same person. Given Wikipedia’s traffic, this makes sense. The fifth-biggest website in the world is visited by millions of daily users, each of whom can edit. For a single individual to “win the race” to make a death announcement would be rarer than lightning striking twice.

Then again, Kranen’s findings complicate the narrative that Wikipedia is run by a small group of supercontributors who make virtually all edits. “I suppose that there might be a bit of a feeling that Wikipedia is just a small number of geeks editing this website, and they probably sit around in a room all day and wait until somebody dies and edit Wikipedia really fast, but that’s definitely not the case,” he said. Research shows that nearly all of Wikipedia is written by just 1 percent of its editors, but there is much more diversity when it comes to death edits specifically. Kranen found that almost one-third of death edits in the sample were made by mobile phone. “Editing Wikipedia from a smartphone is not a very pleasant experience,” he said. “It’s quite difficult actually.” It’s also a departure from normal Wikipedia editing. According to the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit organization that runs Wikipedia in about 300 languages, there were 37 million edits on Wikimedia projects in July 2018—and a mere 4 percent were made using mobile interfaces. It seems plausible that many of these editors are editing from public places. The editor might hear the news about a celebrity death while at a restaurant or a bar, for example, where they would not have access to a desktop and would be limited to a cellphone.

Lastly, Kranen found that about two-thirds of the death announcements were made by anonymous editors. Anonymous editors contribute without logging in, so their edits are credited to their current IP address rather than a username. “Anonymous editors have a bit of a bad name on Wikipedia because they also tend to be the biggest source of vandalism,” Kranen said. He suspected that the anonymous editing correlated with mobile use, since an editor would be less likely to be logged in to their account if they were on a cellphone.

Since two-thirds of these “deaditors” were anonymous, it seemed unlikely that I would ever track them down. But I tried to find some of the remaining one-third. Seattle-based editor Bruce Englehardt, who edited Stephen Hawking’s page as SounderBruce, explained to me over email:

I wasn’t a particular follower of Hawking’s work, but appreciative of his research and knew a decent amount about his life (though I have yet to watch his biopic). As I live on the West Coast, I found out late in the evening with Twitter blowing up after the announcement by the Hawking family. I merely had the fastest hands on the night, having taken a break from writing up the history of two nearby towns (Edmonds and Lynnwood, Washington) for Wikipedia from my home PC … I quickly added a few details about his death, mainly to the introduction (what we call the “lead”) and information box (“infobox”); the changing of tenses and other tedious details were already being worked on by other editors at the time. I then nominated the Hawking entry for the “In the news” section of the Main Page, which acts as a call to action for current events editors to improve and touch up a potential high-traffic page. One of the section’s main policies, like most of Wikipedia, is to leave nothing without a citation of some sort; any existing and unsupported information in the Hawking entry was quickly propped up using whatever links and newspaper articles we could quickly find online or through places accessible from local libraries and Wikipedia-provided newspaper database accounts.

I was very grateful for the thoroughness and clarity of Englehardt’s explanation. Like many Wikipedians, he’s a stickler for citing reliable sources. But I still didn’t have much psychological insight into why an editor might be motivated to make a death edit. Englehardt, who has made more than 42,000 edits to the English version of Wikipedia, is also an exception to the rule that death edits are not necessarily made by power users.

Then I connected with Cameron Banga, who updated the info box on Star Wars actress Carrie Fisher’s page when she died. (Because she died in 2016, Fisher was not part of Kranen’s sample.) Banga said he found out about Fisher’s death via a text from his girlfriend, who works for a popular women’s news website. He described himself as a “moderate Star Wars fan,” who went to Wikipedia to see what other films Fisher had been in and generally learn more about her outside of her iconic role as Princess Leia. “When I saw that no one had updated her death date, I just made the change,” he said. “I didn’t think much about it.” Although Banga regularly reads Wikipedia, he’s definitely not an active contributor. The Carrie Fisher update in 2016 was only the 10th edit he’s made since creating his account in 2012. He hasn’t edited Wikipedia since.

Although Banga made the death edit to the info box, there was actually a flurry of editing activity to Fisher’s page for several days after she died. Editors added additional material to the sections on her personal life, mental health struggles, cause of death, and non–Star Wars work. Today, Carrie Fisher’s page has about 33 percent more words than it did before she died.

To me, this suggests something less sinister than my original Hunger Games comparison: the human tendency to pay your respects. It’s a word and theme that is likely on many people’s minds since hearing the news about Franklin, including those of many Wikipedians. After learning that Franklin was gravely ill earlier this week, MIT librarian and Wikipedia enthusiast Phoebe Ayers tweeted: “dearest Wikipedians, to your editorial stations. GAs [good articles] for this [Aretha Franklin’s page] & all the songs? The whole oeuvre will be hit hard with traffic; we should shine.” Although the formal policy of Wikipedia is that its biographical pages are not intended to be memorials or obituaries, it’s no doubt hard to curb what for many is a natural part of the grieving process.

Sure, deaditing is likely competitive for some, especially those who edit via mobile device. But winning the race to announce a death doesn’t seem particularly rewarding or productive. On the other hand, many of these Wikipedians are likely motivated by a desire to learn, share, or grieve—things that are generally accepted as good and healthy behaviors. Perhaps in Wikipedia as in real life, we are more likely to encounter people than monsters.