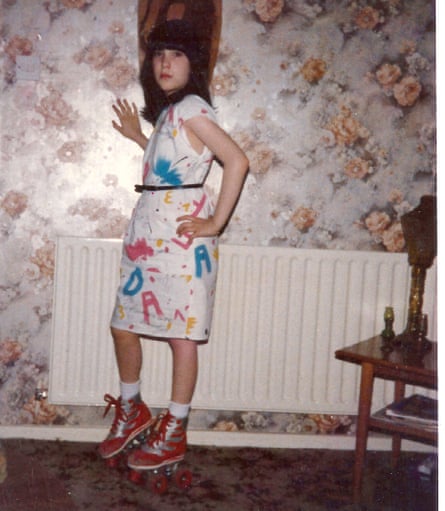

It was a jubilant spring day in 1988. My sister Emily was home for the holidays, having completed her first term at her new educational institution – where she had been sent against her will by social services after years of severe school phobia. Somehow, miraculously, she was happy. There were still a few clouds in the sky – some of the other kids were disruptive, and she missed her old life and family – but it was going to be OK.

I was 12, only a year from being a teenager, and the holidays stretched out before us. Such an atmosphere called for celebration. For us, a real treat meant a takeaway – we usually couldn’t afford them. My dad, Mike, was going to drive to the town centre: there was a chip shop Emily was keen on and it was her special day.

My mom, Jackie (in Birmingham we say “mom” – no one knows why), gave him some money from her purse. I asked to go with him, some father-daughter time, but for some reason he didn’t want me to. I pleaded, pouted; he refused, so I got angry and upset at perceived injustice, the beginning of a tantrum I was probably too old for. As he walked down the hall, I followed him and shouted, “I hate you!” I kicked the front door, but the reinforced dimpled glass could take it. His figure was distorted, a blurry shadow in a blue jumper, as I watched him walk down the path and out of the gate.

A little later, Jackie was in the living room watching TV when the phone rang. It was Mike. He said the queue at the chip shop in town was too long so he’d driven back to our council estate and was calling from the public phone box at the local shops. We should get the plates and chopsticks ready because he’d splashed out on an expensive Chinese takeaway. He was popping to the pub for a quick drink before heading home.

Of course. A quick drink with the change from the money Jackie gave him is likely why he didn’t want me tagging along in the first place. Quick drinks had, with my dad, a habit of turning into long ones. “I got chatting to a mate,” and suddenly it was hours later and his eyes were glazed and his pores leaking booze.

Too much time passed. Emily and I were in my parents’ bedroom because it was the only one with a view of the back car park. It was dark, and he was really late, but it was not the first time and I didn’t feel uneasy. I was on the left, leaning on the windowsill, Emily on the right, watching and waiting. Then, suddenly, something different.

“A panda car!” I said. I’d recently learned that phrase and was excited to have a reason to use it. The car pulled up in the car park and a uniformed officer got out. I watched him look around – probably looking for one of the houses opposite, one of the problem families. Not our family – we had no problems that day.

We watched the police officer walk down the narrow path behind our row of back gardens and disappear out of sight. Our estate was a labyrinth, full of alleys and dead ends. It took about three minutes to walk from the back of our houses, down the alley and around to the front. Three minutes of hope. Three minutes of being children. Three minutes passed by, the rest of my life. There was a loud knock at the front door.

“There’s been an accident, Mrs King. Your husband has collapsed.”

The police officer at the door was a hundred feet tall. Emily and I stood behind Jackie in the doorway as he explained that he couldn’t fit us all in the panda car: was there anyone who could drive us to the hospital, perhaps a neighbour or friend? Jackie made several calls and someone from our church said yes, he’d come.

We were given our own waiting room. It had half a dozen hard plastic orange chairs. I sat next to Emily. My feet didn’t reach the floor. Jackie paced. A doctor arrived and gently explained that Mike had collapsed and an ambulance had brought him in. He was on life support. “We believe he had a brain aneurysm,” the doctor said. “It can happen.” People walk around with a little bomb in their head for years, unknowing, until suddenly it explodes and they collapse. I imagined a cartoon bomb with a lit fuse slowly burning in my dad’s head, until one day – today – it goes boom. Did I have one, too?

“Is he going to wake up?” I said. I didn’t ask if he was going to die because my dad couldn’t die. That wasn’t in my worldview.

The doctor spoke in a kind but sad tone. The chances of recovery were slim, he told us. If Mike did wake up, he would likely have brain damage, might be in a vegetative state for ever. My brilliant, funny, kind father. Mike, who taught us everything, including the Greek alphabet, sowing seeds of curiosity for us to nurture and, later, harvest. Mike, who did a broadsheet cryptic crossword every day, and challenged us with logic puzzles and games. Even his alcoholism was gentle, making him silly and sleepy. I imagined him in a wheelchair, drooling, being spoon-fed, not knowing who we were, in pain he couldn’t articulate. My heart broke as I prayed and prayed for him to wake up and be fine.

The next morning, Emily and I were with our grandparents, waiting for the phone to ring. We were hoping Jackie would call and say Mike had woken up, he was OK, we could go and see him. When the phone eventually rang, my grandma Bernice answered. She talked to Jackie for a while, then put the phone down and faced us, shaken and crying.

“The doctors have asked your mom for permission to turn off life support. They said your dad is brain dead. He isn’t going to wake up.”

Brain dead. I was numb with shock. Then I heard a strange, unrecognisable noise. My grandad was crying, a choking hiccup, until Bernice, also in shock, shouted, “Stop it, Symon,” in a desperate attempt to arrest the grief and potential hysteria in the room.

Over the next few days, we absorbed the news. People came and went. Church, neighbours, family. I heard the same words over and over. Brain aneurysm, ticking timebomb, life-support machine, the end. Then suddenly the atmosphere shifted as Shannon, a friend of Emily’s, ran breathlessly into the house with urgent news. At the shops where Mike had collapsed there was now a police crime scene. We looked at each other. Jackie agreed we could go but told us to come straight back.

I had seen this view my entire life. The red-brick pavement, people coming and going, the telephone box where Mike had made his call. These were cordoned off in a wide area by blue and white police tape.

Shannon and Emily hung back, nervous and unsure, but I wanted to get answers. The police officer standing guard was intimidating, but I confidently approached him and tried to summon an assertive voice. “Excuse me, can you tell me what’s going on here?”

“What have you heard?” he asked carefully.

“All I know is, my dad collapsed here the other night and now there’s this.”

“Ah,” he said, crouching to my height, his tone shifting into kindness. “Well, we’re just trying to find out what happened, see if anyone saw anything.”

The three of us headed home. When we arrived, there were two strangers in the house.

The detective chief inspector had a moustache, a Welsh accent, and the largest beer belly I had ever seen. DCI Burns explained that things were not as straightforward as the hospital had first thought. All police leave had been cancelled and a team of CID officers drafted in for a manhunt. My dad’s death was being investigated as a murder.

Who would want to kill my dad? The answer, when it came a few days later, was as unexpected as a brain aneurysm.

A newspaper article headlined “Youths quizzed on death” claimed he had been “found slumped outside a telephone box”, a police spokesperson saying, “We are treating this as a very suspicious incident. Four boys, aged 14 to 16, are helping us with our inquiries.” Police had arrested a gang, first four, then a fifth young man, on suspicion of murder.

DCI Burns returned to see if we recognised their names. Andrew Reynolds, the oldest, was unknown to us, as was one of the younger boys. Two others were former classmates of Emily. The final name, Reece Webster, was all too familiar. He lived a few doors down. The quiet, serious, under-nourished, isolated boy with intense eyes, whom Jackie shouted at when his football hit our window. We knew him, and he knew us. And now he and his friends had been arrested for my dad’s murder.

The “random brain aneurysm” version of Mike’s death is something I might perhaps have had a chance of getting, if not over, then past – something tragic but just about conceivable. But a murder is not that, not at 12, and not without a stable environment and resources. Twelve is the perfect age to feel the full, adult force of a crime but without the emotional maturity to handle it.

I got used to scouring the paper, at once desperate for and dreading any mention of Mike’s name or the boys’. The following week, the local paper announced the “youths” had been released on bail. As Webster lived a few doors away, and the rest not too far, the chances of bumping into one of them were high. Jackie and I had no idea what three of the five youths looked like. We could have passed them anytime. Every white teenage boy in a tracksuit jacket could have been one of them, every innocent group of lads the murderous gang.

DCI Burns told us what he believed happened that night, a story pieced together from theory and witnesses: that while Mike was in the phone box, a gang of bored youths had started to mock him. Mike went to talk to them and Reynolds, the ringleader who did martial arts, had jumped from the wall, landing an expert karate chop to the back of Mike’s head, killing him instantly. Without pausing to see if he needed help, the gang fled.

DCI Burns visited a few more times. He told us the boys were insisting they were innocent and were at risk of vigilante justice. One had been cornered outside the pub and threatened by “friends of Mike”. I didn’t want anyone to harm them: I wanted proper justice, through the court. How would more violence help anything? My whole family had recently converted to born-again Christianity and an-eye-for-an-eye was too Old Testament for me. I felt even more unsafe. Eventually the Crown Prosecution Service decided to proceed with a single manslaughter charge against Reynolds.

Over the next year, I fell into a serious and angry depression. It’s not that I wanted to die, more that I just wanted to stop. I felt furious, rebellious and frustrated at not being heard or understood. More of an animalistic scream than a cry for help. I thought about death constantly, until it seemed like a place I could go, too. I would lie awake replaying the dramatic scene of my dad’s death, as vivid as if it was my own memory and not just a tableau conjured from a story heard via unreliable narrators. I thought about Reynolds jumping off that wall, hand in a karate chop, body frozen in midair.

I couldn’t sleep, so Jackie took me to the doctor. I didn’t mention the obsessive repeating of violent images all night, and he gave me sleeping pills. I didn’t like taking them. If you get drunk or do drugs, you lose control and someone will die, I reasoned. But that was calm me. Angry me had no control whatsoever and became hysterical over the tiniest things. During one episode, I ran upstairs, grabbed my sleeping pills from the floor of Jackie’s bedroom where I spent my nights, and sank down in the corner, sobbing desperately.

My mom came to find me and prised the open bottle out of my hand, screaming, “Did you take them?” I refused to tell her. Even in my rage and grief I realised I wanted her to think I had. She was in hysterics herself then, and our roles shifted. I had the power. I told her I hadn’t taken any pills. They were still in the bottle and the extreme frustration that had driven the whole awful thing was gone. I was left exhausted and overwhelmed by the guilt of my newly widowed mom thinking, however briefly, that her child had wanted to die, too. Our church – the fire-and-brimstone fundamentalist sort who had sent missionaries from America to recruit vulnerable people on council estates – suggested I was possessed, and performed an exorcism. It didn’t work.

We had been told the trial would likely last five days. On the second day at Birmingham crown court, Emily and I settled into the waiting room chairs. We had been so primed by the police about the events of that night, I didn’t expect anything but a long trial and a guilty verdict. At 13, I was too young to be allowed into the courtroom. Jackie said it was for the best anyway, as the trial would be too upsetting.

I hated those teenage boys, was petrified of them, but I had seen Reynolds’ parents in their distress outside the courtroom and struggled with the police’s image of him as the malicious, violent gang leader. Perhaps, I reasoned, that was why the charge had been reduced to manslaughter, though this did nothing to lessen the pain of a violent death. “My dad was murdered” had been in my head for a long time. There is no equivalent phrasing for this. “My dad was manslaughtered”? It’s not a thing. Someone had hit him on purpose and he’d died, but that someone hadn’t meant to cause his death? That didn’t tally with the police’s description of a malicious karate chop.

Then the courtroom doors flew open again and my entire family streamed out, livid with boiling disgust. Emily and I jumped up, confused. Someone told me that the case had ended prematurely. “The judge has thrown it out!” Reynolds was free.

Everyone around me seemed horrified at what must surely have been a grave miscarriage of justice.

I saw Reynolds from a distance as he was released into the corridor, a boy much smaller than his age, joining his parents who were visibly overjoyed as they accompanied him down the stairs and out of the building.

after newsletter promotion

As the decades passed, I thought about the boys from the gang as little as possible. I had no feelings of anger or even blame, having long made my peace with the chaos of it all. I left religion behind when we moved away from the estate, and built a career in science communication and critical thinking. My job requires me to ask hard questions, check evidence, put bias and feelings aside and consider the facts even when doing so is hurtful. But I had never done that for the events of my father’s death. Until now.

I wondered if Reynolds had given it any thought in the years since, whether he had even seen the little girl outside the courtroom or heard the shouts of my family. I wondered what sort of person he’d become.

We’d never met, so I had no real sense of him. But that wasn’t true of all the boys in that gang. I had known my neighbour Reece Webster, knew he was not a bully, never teased us or called Jackie a witch, as other kids sometimes did. We played together. He was not a stranger to me before the night Mike died. Perhaps he wasn’t a stranger now.

In early 2020 I found a way to contact Webster. I reassured him I wasn’t harbouring any ill will or blame; I was trying to piece together a few things. He agreed to answer my questions, and we arranged a video call.

The screen flickered into life and there he was, sitting in his home. I stared at the man for signs of the boy, and was puzzled to discover I could not see him. His face was familiar, yes, but in the way that you can’t figure out where you know someone from. There was just a slightly familiar, serious but otherwise ordinary man.

“Hello!” I said, putting on an upbeat tone to disguise my nerves.

“All right,” he replied. His accent was way more Brummie than mine. It surprised me, but that accent always feels like home.

I was very nervous, and the talk was small. In my career I’ve worked with some extraordinary people, from astronauts to rock stars to Nobel prize winners, but this was the most challenging conversation of my life. I needed to hear what he had to say about Mike’s death, but he had to relax and trust me. When it came, the story he told me was not what I expected. It was not what I expected at all.

Webster had recently turned 14, but had never been involved in a fight before. He and his friends spent most of their time playing football or video games. His mother had recently left, and his father was frequently absent.

The night of Mike’s death, Webster and his friend, without anywhere else to go, headed to the shops with another boy. They’d all had minor trouble with the police, but nothing unusual for the estate. They found themselves sitting near, but not with, another boy, also 14, who was talking to an older boy, Andrew Reynolds –

“Wait. You didn’t know him?” I interrupted.

“Not at all. He was nearly 18 then. He never spoke to me. I didn’t know where he lived. I didn’t know about his family. We didn’t know anything, really.”

What happened to the marauding gang of five, the older ringleader? It was suddenly nowhere. The gang did not exist. Instead, there were five individual boys along the wall, each with their own reasons for being there.

I spent two hours on Zoom with Webster that evening and he told me his version of what happened. It was not the version I had lived with for 35 years. Instead, Webster told me about an argument gone wrong, in which my dad was not the luckless victim I had always wanted to believe. My childlike notion of heroes and baddies, good and evil, had to dissolve, to be replaced with a complex, messy, sudden insight into who my dad was when he wasn’t being my brilliant father.

Reynolds – not a black belt in anything – did not jump off a wall and land a karate chop to the back of my dad’s head, but clumsily defended himself in the scuffle as my dad lunged towards him. They tried to help my dad after he collapsed. A couple of adult men came over and one told the boys they “had better scarper”, so they did. Webster was certain they would not have left the scene otherwise. And the next day the four younger boys met up; one of their dads had arranged to call the police. As none of them knew Reynolds, they did not contact him.

The four boys were arrested on suspicion of murder, held and questioned separately for several days, then released without charge (not on bail, as the newspaper had reported). Webster said that he was physically and verbally abused in custody. He shook when he said it. After he was released, he tried to go back to a normal life, but an arrest for murder sticks. His grandmother stopped speaking to him; his relationship with his parents declined even further and he was left to his own devices, not even on the radar of social services.

So much of what he said made sense, and so much of it was unbelievable. If his version was true, why would DCI Burns have told us differently? If Webster was telling the truth about that night, I had to find proof.

Summer 2021. I sat in the passenger seat of a car, clutching a sealed A4 envelope with “Tracy King” handwritten on the outside. Inside were the detail and facts of Mike’s death. The hard proof, or as hard as I was ever going to get. A copy of the original 1988 police report. It had taken me a long time to get my hands on it.

DCI Burns’s report ran through the events of that day, from the time my dad woke up at approximately 8am. Burns said he had found “no evidence to suggest he consumed alcohol on the day of his death”. There was nothing in the report about my argument with Mike. It suggested he was happy, celebratory, as he should have been, given Emily was at home. But in general he was also anxious, depressed, trying to quit drinking. The report seemed to want a definitive mood, some certainty about his state of mind. There was none to be had.

Most of it confirmed Webster’s version. In his witness statement he said one of the boys (not him) called Mike “a bald-headed bastard”. As a provocation, it is both absurd and banal. My dad carried a small comb and he’d let me style the sparse patch that constituted his comb-over. He taught me the principles of static by rubbing a balloon on his jumper and raising those few hairs straight up like magnetic magic. But Mike’s baldness could clearly be used as an insult as much as a joke, and perhaps that was what crossed the line of disrespect and caused the argument to turn physical.

Then there was the section on Mike’s death. It was about the five arrested suspects and whether they committed murder. The report’s conclusion was that, based on the evidence of witnesses who saw certain aspects of the dispute, and that of the suspects, they did not. DCI Burns stated he believed it was probable that Mike instigated and participated in the physical violence. Which made what Reynolds did self-defence, and it’s why, a year later, he was rightly acquitted.

Of all the detail in the witness statements, the paragraph that changed my perception most was this: “While these youths did momentarily disappear they returned once King had been taken away. They spoke to Smith [one of the adults who told the boys to scarper] who said he thought the man was dead, this caused a great panic among the youths, some were physically shaking while others cried.”

DCI Burns said in the report, “Had it not been for the irresponsible behaviour of Smith, who frightened these youths away from the scene, there is no doubt that all five would have remained at the scene to explain the situation to the authorities upon their arrival.”

The report was a time capsule in which I relived the worst version of events as they unfolded. Murder. Gang. Karate chop. The jump off the wall. It was all in there, unreliable snippets from other witnesses who admitted they couldn’t really see what was going on. As I read, I saw every piece of the original story and how, together, they looked like something that they were not.

I had to accept that the version of events I, and my entire family, had lived with since 1988 was not the truth. A simple principle of critical thinking is that you cannot prove a negative. Another is that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. I cannot prove what did happen, but I can discount what did not. The biggest clue to why we had that version of events in the first place is hidden in DCI Burns’s tactful conclusion to his report. He wrote, “As it develops [sic], the circumstances presented themselves in a more criminal and sinister manner than perhaps they deserved.”

Burns basically admitted the dramatic murder inquiry was simply overkill. But my family didn’t get the message.

In his book The Demon-Haunted World, the astrophysicist Carl Sagan admitted, “But I could be wrong.” That was the flashpoint for how I learned to think, and I’m grateful for its liberating power. I had believed, sworn by and then conveniently ignored an elaborate story about Mike’s death, and the truth – while no less devastating and in many ways harder to live with – is more mundane. Simply put, I was wrong.

I finally met Andrew Reynolds in person in late 2022, returning to my old home town to meet him in a pub. He seemed nervous, so I kept up a stream of reassuring chat as we got soft drinks and found a seat. We had spoken on the phone several times and I trusted him. I thought he’d perhaps want to avoid the subject of Mike’s death, but he jumped straight into the big talk. Reiterating what he had told me on the phone, he spoke with sincerity and nerves. It had clearly affected him deeply, his whole life. He told me barely a week had passed that he hadn’t thought about it, how it all happened so quickly and how he tried, in vain, to help Mike.

I looked at his hands as we talked, thinking about how simply a man had died from being struck, and how the karate chop that never happened had haunted my psyche. We talked about how tall Mike was compared with him. I did not know my dad was tall until I read his autopsy report. He was over six feet, and the abstract image I had of their altercation suddenly came to life, my dad towering over this person in front of me.

I asked Reynolds how he felt at the time, thinking he would go to prison, and he told me how scared he had been. He remembers little about the trial, but said he saw my sister and me as he left the court. I was glad he noticed and remembered us.

He said again how sorry he was. I said I was sorry, too, but that it would all be OK. As we stood up to leave, I thought about shaking his hand, but instead opened my arms for a hug.

Some names have been changed.