There’s a 2013 Black Mirror episode in which a young widow played by Hayley Atwell signs up to an online service that scrapes a person’s entire digital footprint to create a virtual simulation. She soon starts chatting online with her late husband (Domhnall Gleeson), before things inevitably get Black Mirror-y.

Laurie Anderson, the American avant garde artist, musician and thinker, hasn’t seen the episode but, in the last few years, has lived a version of it: growing hopelessly hooked on an AI text generator that emulates the vocabulary and style of her own longtime partner and collaborator, Velvet Underground co-founder Lou Reed, who died in 2013.

“People are like, ‘Wow, you were so prescient; I didn’t even know what you were talking about back then’,” she says on a video call from New York.

A new Anderson exhibition, I’ll Be Your Mirror, has just opened in Adelaide, where Anderson will be doing an In Conversation event via live stream on Wednesday 6 March. The last time Anderson was in Australia, in March 2020, she spent a week working with the University of Adelaide’s Australian Institute for Machine Learning. Before the pandemic forced her to catch one of the last flights home, they had been exploring language-based AI models and their artistic possibilities, drawing on Anderson’s body of written work.

In one experiment, they fed a vast cache of Reed’s writing, songs and interviews into the machine. A decade after his death, the resulting algorithm lets Anderson type in prompts before an AI Reed begins “riffing” written responses back to her, in prose and verse.

“I’m totally 100%, sadly addicted to this,” she laughs. “I still am, after all this time. I kind of literally just can’t stop doing it, and my friends just can’t stand it – ‘You’re not doing that again are you?’

“I mean, I really do not think I’m talking to my dead husband and writing songs with him – I really don’t. But people have styles, and they can be replicated.”

The results, Anderson says, can be hit and miss. “Three-quarters of it is just completely idiotic and stupid. And then maybe 15% is like, ‘Oh?’. And then the rest is pretty interesting. And that’s a pretty good ratio for writing, I think.”

On her side of the call, Anderson starts typing. “You know what, I’ll just bring it up right now while we’re talking and you can give me a phrase.”

Looking at the morning traffic outside my window, I offer the very mundane, “bus idling on the street”. She feeds it in as we keep talking.

Back in 2020, Anderson said the institute’s work was “like collaborating with the biggest brain you could imagine”.

This was before ChatGPT and Midjourney, when for most people AI remained a far-off concept without mainstream applications – just fodder for sci-fi.

These newer developments have brought fresh creative, ethical and legal questions, from concerns over AI porn to copyrighted works being used without permission, to “fake” songs made by digital doppelgangers of real, living artists such as Drake and the Weeknd.

Some of Anderson’s peers have been scathing; confronted with lyrics written in his own style by ChatGPT, Nick Cave dismissed it as “a grotesque mockery”. (Even worse, perhaps, he said, “this song sucks”.)

Anderson appreciates those reservations, which run deeper than the latest uncanny innovations.

“It just made me think about a Čapek play from 1920: RUR, or, Rossum’s Universal Robots,” Anderson says. “It was a play about robots taking over the world – people 100 years ago were very worried that robots were going to take their jobs, and take over, and be evil. I think ever since a golem was invented, people are afraid of that, you know?”

after newsletter promotion

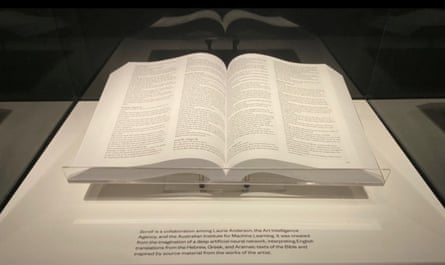

The first thing the institute created using Anderson’s input had a similarly Old Testament quality, generated by an AI Laurie Anderson.

“It was a 9,000-page document [written] in my style, telling the stories of the Bible. It was deeply creepy, and really fun. Because the Bible is already insane – a snake that was talking? A guy who lived for 800 years?”

This week, the AI-generated Bible and other works created by Anderson and Reed’s doppelgangers will feature in I’ll Be Your Mirror, exhibited at the State Library of South Australia as part of Adelaide festival. Anderson won’t be making the trip this time but will dial in for a few talks – the steady ping of emails arriving throughout our conversation hint at the 76-year-old’s relentless schedule.

I wonder if, after being given a lifetime achievement award at the Grammys in February, the prospect of these algorithms continuing to make “Laurie Anderson” art beyond her own lifetime has caused her to reflect on her legacy.

“Oh, why not? I mean, that doesn’t bother me. I don’t feel that attached to time anyway, you know?

“When people die and you hear their words or hear their music or read their things, it’s like they’re alive, you know? In many ways, there they are. You can say that about Dostoevsky, Plato, you know, the Buddha. People leave things around, and so I feel fine about that. I mean, we’re just mayflies, really.”

When the ghost in the machine has finished thinking, it serves up some fresh Lou Reed-ish lyrics inspired by my bus stop:

The street and the sky

When you die

I’ll be sitting in an idling bus

On my way to work

And no more

Than ten minutes before

The last train of the day

Pulls into the city, the light

Dim, insubstantial at first

Then less than a sliver of that

In half a second it’s all

You’ve got to live it, as they used to say

So much can go wrong

But why did you think this

Was a good idea

Don’t you get paid enough

To pay taxes? Why not play

Some tennis or take up quilting

Or improve the sanitation

Of this vast and sordidized

Island from which you sail

Is it such a wonder you’re alive

After all this sugar-fied waste

One cigarette, a glass of wine

Tell me, do you like it

How does it make you feel

Do you like the bitter taste

I ask if Reed referenced “quilting” a lot in his writing, and Anderson laughs with her usual mix of playful and profound:

“Hah, I think that might be the first time.”

I’ll Be Your Mirror runs until 17 March as part of Adelaide festival. Laurie Anderson will be speaking via live stream at an In Conversation event on Wednesday 6 March, as part of Adelaide writers’ week

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion