CRUNNNNCH!

SKKKZZRRRR!

JJJUUUGGGGLLLLZZZZZ!

In my balls, I could feel the violent vibrations as layers of Epifanes spar varnish, quite dear in both price and labor, were mercilessly toothed from the hull of my canoe by river rocks. To be fair, I could also feel the scraping tremors in my feet, legs, and buttocks as we banged along the river bottom in yet another stretch of shallow water. But it was my familial plums that spoke with the most immediacy, because there was something existential going on that afternoon in L.A.

In the 25 years I’ve called the city my home, I’ve done a great many things that I would categorize as fun. I have, of course, worked as an actor. But I’ve also been paid to build various decks and cabins as a carpenter, plus one exquisite post-and-beam yoga studio. I worked as a production assistant on a few music videos, trained by a tall, handsome, surfing porn actor who taught me to get up and stay up (but only in the surf). I constructed an octagon-style wrestling cage for an episode of Friends. I’ve hiked hundreds of miles’ worth of trails in Los Angeles County, some while hallucinating, but mostly sober and high on the views from Griffith Park, the San Gabriels, and the Santa Monica Mountains. Yes, this has become a paragraph of bragging. The point is, the one thing I never dreamed I would do is launch my beloved handmade cedar-strip canoe, Huckleberry, into the concrete-clad L.A. River, just a few miles north of the location of the drag-race scene in Grease.

If you can recall that iconic moment, in which Cha Cha DiGregorio orgasmically whips her silk scarf off to begin the race between Danny Zuko in Greased Lightnin’ and the jerk whose jalopy was so lame it didn’t even have a cool name, then you might be thinking: Where the hell does a canoe fit into that expanse of concrete?

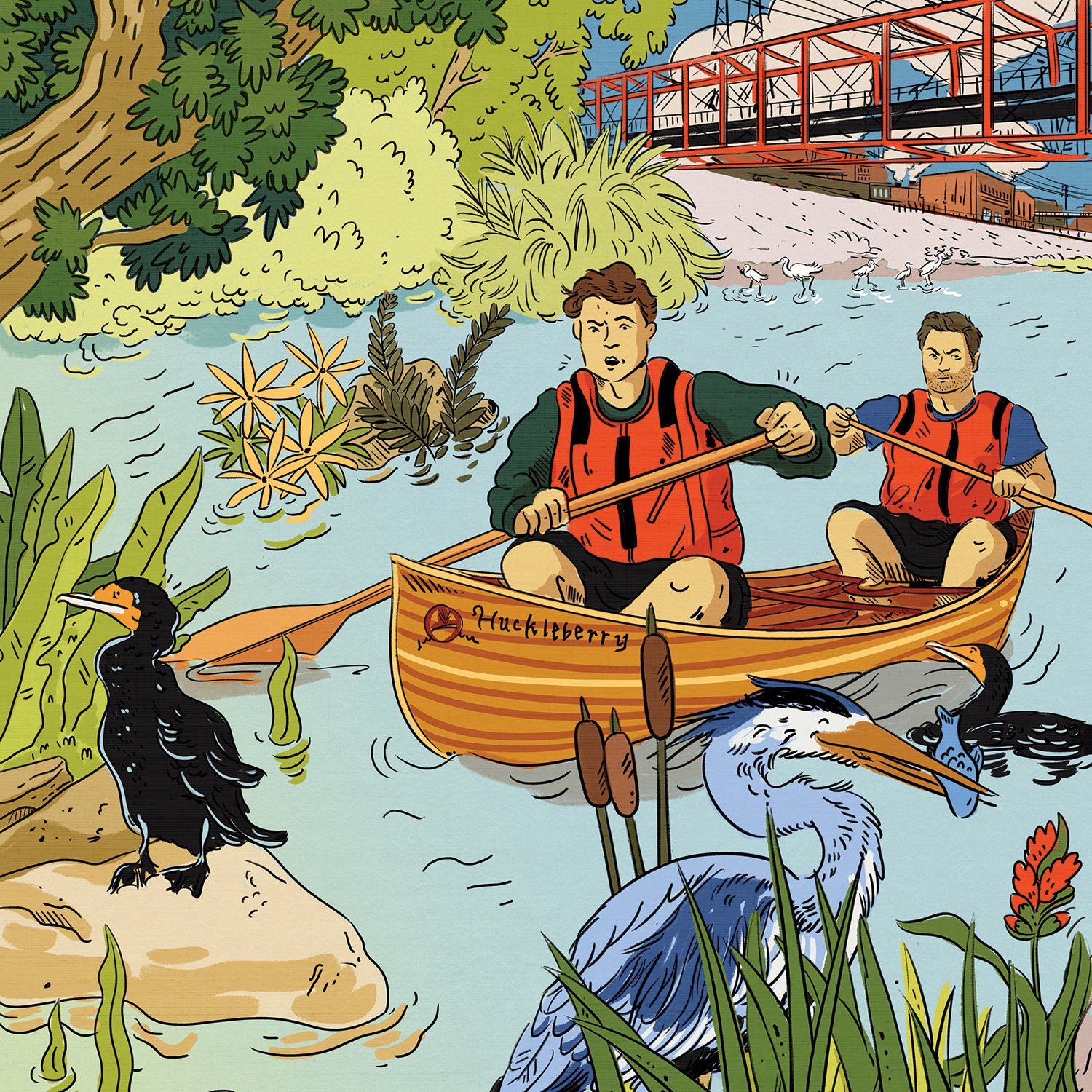

According to my guides, Steve Appleton and Grove Pashley of L.A. River Kayak Safari, the answer lies in a section known as the Elysian Valley, just down the hill from Dodger Stadium. As explained on the LARKS website, in this stretch “a high water table and the dynamics of the river’s bends around the local hills left a soft bottom … creating an environment for aquatic plants, fish, birds, and humans.”

I put in at the outfit’s headquarters an hour ago with my bowman, Morgan, and since then Steve and Grove have nimbly paddled along with us in kayaks, flitting about alternately fore and aft, scared shitless at the idea of me dragging Huckleberry across the many shallow stretches in the several miles of river we hoped to complete.

Some five minutes after first dipping our paddles, we suddenly found ourselves T-boned against a boulder by a waist-deep current.

Their concern was amplified by the fact that Morgan and I were now soaking wet. After launching, we had remained upright through a couple of wobble sessions in the river, in that way you do when first setting off in a canoe. As a team, you discover the limits of how far you both can lean while paddling, sightseeing, ass scratching, or snagging a beer (if the sun has traveled far enough into its morning’s arc, of course, depending upon the traditions of comportment in your particular barque). We were busy spotting herons (great blue and green) and egrets (great and snowy) while zipping past lush foliage, luxuriating in a smooth 50 yards of gushing creek before bumping back into the intermittent rocks and shallow water, when, some five minutes after first dipping our paddles—whup! shit!—we suddenly found ourselves T-boned against a boulder by a waist-deep current.

Huckleberry neatly flipped us out, and we immediately set to righting it and dumping out the many gallons of river that had filled its rounded hull. Steve paddled over to lend a hand, as it was both arduous and somewhat dangerous work, in the way any task can be when requiring the exertion of strength on slippery rocks in the face of rushing water. When we succeeded in once again taking our seats, it became apparent that in our swift blunder and its subsequent correction, Morgan and I had established a few things for our gentle guides: (1) we were suitably tough and skilled to be trusted on the day’s outing; (2) I was enough of a dipshit to willingly bang around my pristinely refinished canoe; and (3) we were dumb enough that this might just turn out to be fun.

But now, as I sat in Huckleberry with my love marbles buzzing after maybe the 50th crunching encounter with river rocks, my three compatriots asked me once again, as they did throughout the day’s adventure, “Are you sure you want to keep going? That canoe’s taking a beating.”

I get it. People see a beautiful handmade wooden canoe and they want to hang it up in the living room and ogle it like a poster of Kim Kardashian’s impossible caboose, and not just because both boast a sturdy monocoque construction. It’s a goddamn swoon-inducing, curvaceous work of art (the canoe).

I learned to build canoes from the seminal 2007 instruction book Canoecraft, written by Ted Moores of Bear Mountain Boats up in Peterborough, Ontario. Ted and his partner, Joan, were pioneers in the development of cedar-strip canoe and kayak construction, utilizing fiberglass and epoxy finishing, though they would be quick to point out that their designs are but the current progeny of a long lineage of hulls, dating back centuries to the ingenuity of the Indigenous peoples of eastern and northern Canada. In 2008, I arrived in Manhattan with a bag of hand tools, at a time when my legendary bride, Megan Mullally, was cast by Mel Brooks in his musical version of Young Frankenstein.

The vacation from my L.A. woodshop and furniture clients meant that I could fulfill my dream and build my first wooden canoe. Being all too aware of the old chestnut about the basement-built boat failing to fit out of the house, I secured a shop in the Red Hook area of Brooklyn, on the third floor of a Civil War–era stone warehouse perched on a pier and complete with a huge freight elevator. Crisis foreseen and averted.

When finally you are faced with the choice between the comfy living room and the unpredictable outdoor jaunt, there is but one clear answer: Do the goddamn thing.

The most important lesson in Ted’s patient lesson book comes at the beginning. He says that when you consider the whole canoe, it can seem impossible to build without years of training, but if you take it one step at a time—trace a shape, cut it out with a jigsaw, glue a couple pieces together, and so on—then before you know it the boat will emerge as though you just spun a chrysalis.

If it hadn’t been for Megan’s timely turn burning up the Broadway stage, I would likely have continued on in California, building ever more substantial homages to the table stylings of George Nakashima, Sam Maloof, and Gustav Stickley. But since the East Coast diversion had pulled me out of that potential rut, I experienced a powerful epiphany: shaping curved pieces freehand—with spokeshave, card scraper, chisel, and rasp—was to become like a god.

You see, most woodshop operations are set up to work on rectilinear forms, creating and cutting and joining square and plumb surfaces and corners to make many variations on the box, usually featuring 45- and 90-degree angles. But a canoe has exactly zero straight lines on it, so one sculpts its gunwales (“gunnels”) and thwarts and shapely bottom until one’s eye and caress pronounce its lines to be “fair,” thus creating an affection for the final product that transcends the love one might feel toward, say, a three-legged stool. Throw in a couple of custom, hand-carved paddles and I had fully reawakened that part of my youthful fancy determined to find a way to Narnia. Imagine the faerie magic in my every dainty step as I hoisted the completed Huckleberry upside down onto my shoulders for its inaugural portage to the freight elevator. Victory was upon me—shit.

My compatriots lightly gasped and made noises like those prompted by minor stomach pain.

As I said, the elevator was huge, but my canoe was 18 feet long. She would not come close to fitting, even on a diagonal. The small stairways were obviously not an option either, so my pal Jimmy DiResta and I rigged a block and tackle from an old freight hook on the roof and gamely hoisted it out the window and down to the pier.

Ted and Joan had traveled down from Bear Mountain Boats to see the launch, and Ted (generously) said that my work was exquisite, which made me cry, but only a medium amount. We were all on eggshells watching Huckleberry descend from a third-story window, but Ted said that he’d seen these canoes survive worse falls than that. The engineering of the form, plus the makeup of the shell, make them tough enough to survive even the dumbest of actors.

Over many creeks and rivers over many years, I have learned the hard way that Huckleberry can gamely scrape across a lot of rocks and gravel while suffering only minimal cosmetic damage. Still, do I wish that I had run the L.A. River before applying three brand-new coats of varnish to it only weeks earlier? Yes, I do wish that. I wish that so very much. But you can only strategize and try to account for every potentiality up to a point. When finally you are faced with the choice between the comfy living room and the unpredictable outdoor jaunt, there is but one clear answer: Do the goddamn thing. Drop to your knees in the mud. Get your hands dirty, wipe ’em on your shirt. Paddle your canoe down a fun expanse of weird urban river that might scratch it up. Why did I spend so much time and care building this watercraft if I don’t intend to get some thrills out of it?

Onward we went. The route through the Elysian Valley has a delightful mix of fast-moving chutes, medium twists and turns, a four-foot waterfall, a couple of brief portages (for canoeists), and two pond sections where the flow slows into a laconic, deep-water float, perfect for taking stock, bird peeping, and, well, ass scratching and beer snagging.

One true surprise was how clean the water was. Steve and Grove founded LARKS in 2013, partly as a way to support conservation efforts for the river. (Grove left the organization seven years ago but remains a close ally.) Today LARKS has a healthy relationship with a bunch of nonprofits and government agencies like Friends of the LA River, LA Waterkeeper, the Council for Watershed Health, and the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority.

But the focus on water quality dates back more than 20 years, when Steve, who is a sculptor by day, crafted a waterwheel that he placed in the river, plumbing it to an experiential artwork that collected and filtered the (then filthy) river water to make it, he says, “clean enough to drink.” This led him into a close working relationship with the City of Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, which maintains so-called water-quality beacons that serve as stop and go lights for L.A. River recreation. Of the 108 tests done in the Elysian Valley during the 2023 paddling season, 92 percent met EPA requirements for safe swimming. The nine exceptions (measurements usually taken after a storm flushed in dirt and waste) met a slightly lower standard that is still perfectly fine for canoeing and kayaking.

All I can say is that Morgan and I were impressed (and relieved) that the river smelled … perfectly fine. The water was also visibly clean, which added to the surreal quality of paddling through an industrial corridor between the 5 Freeway and a main train artery for both freight and passengers. In the section they call the Secret Pond, the water was over ten feet deep, and things got downright otherworldly as we calmly floated, chatting in a quiet reverie about the American coots swimming near the shore and then walking up the concrete bank with their strange, big-toed feet. A minor bloop caught my ear—a pair of double-crested cormorants surfacing right next to us, then diving back down into the depths of this unlikely fishing hole.

As our venture drifted to completion, we were left wanting more, which is utterly preferable to that feeling every paddler has known: Ugh, this is too long! When are we getting there?! I’m always a little melancholy when the hull runs lightly aground for the last time and we have to climb out of the cedar escape pod and step back into the reality of life on terra firma.

We flipped Huckleberry over to reveal a cluster of battle scars: a web of bright white abrasions against the golden honey brown of the varnished cedar. My compatriots lightly gasped and made noises like those prompted by minor stomach pain, but I shook my head and said: No, boys, don’t be sad. Those gouges are just telling us that we spent the day correctly. I’ve mended them before, and I’ll do it again.

Nick Offerman’s column for Outside magazine has him regularly repairing gear, washing cow butts, and getting outsmarted by raccoons. He’s fine with that. He also just won his first Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama Series for an episode of The Last of Us.