“Please I Will Give Anything for You to Come Back”

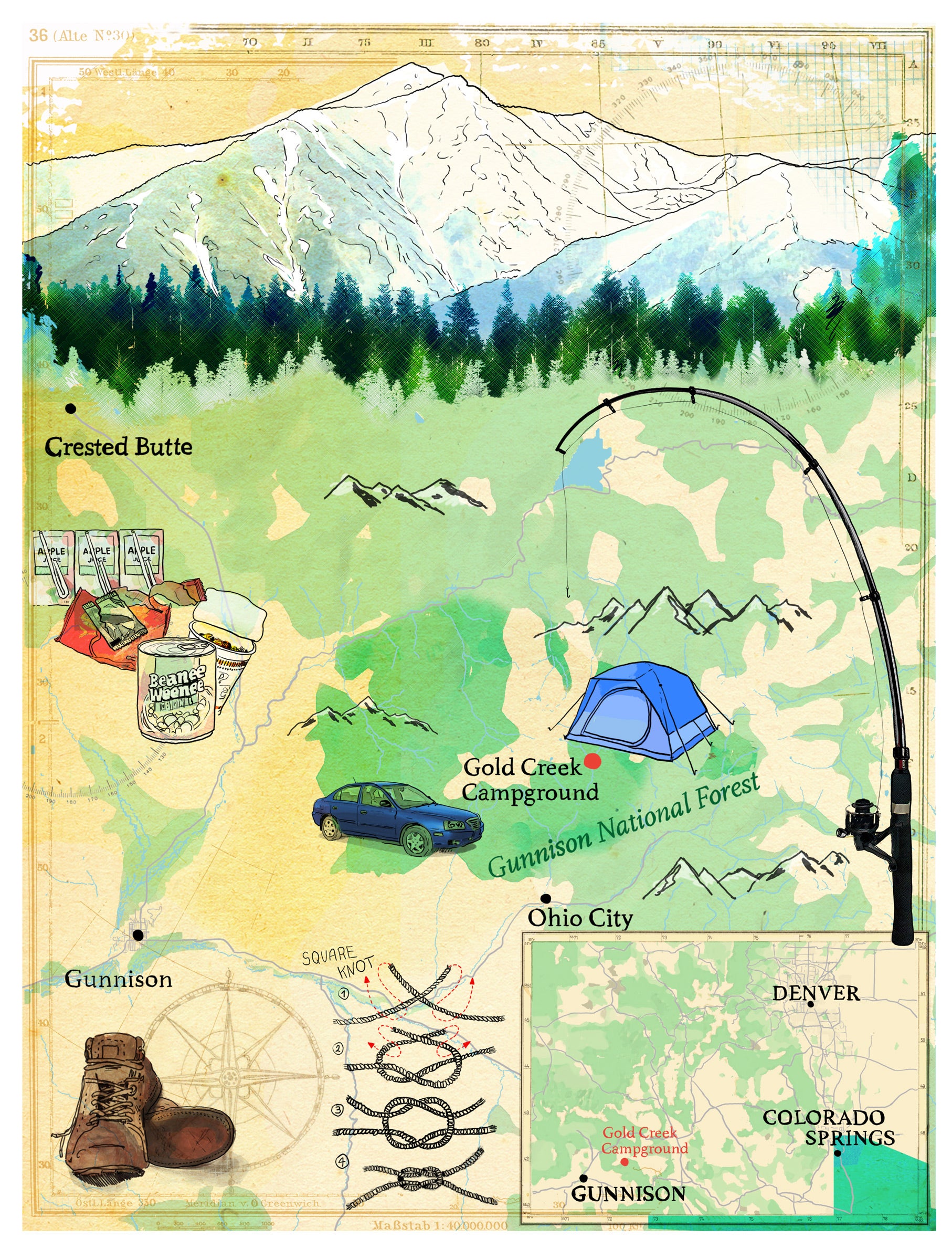

Why did a mother with no backcountry experience take her sister and 13-year-old son to live off the grid on a 10,000-foot mountain during a Colorado winter?

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Talon Vance, 13, lived in an apartment complex in suburban Colorado Springs with his mom and Aunt. Other relatives lived nearby. Typically, he spent much of the week with his father, half brother, half sister, and grandparents, all of whom lived together not far away in a different town. All of that would change in August 2022: Talon’s mother, Rebecca Vance, had hatched a plan to disappear from Colorado Springs and go permanently off-grid.

Talon’s paternal grandmother, Marilyn Burden, still seems shell-shocked by his sudden departure. Her extended family lives in a ranch-style house on a small cul-de-sac; when I stopped by for dinner last September, there were plenty of people on the street, and lights were on in every home. Eric Burden, Talon’s father, stood in his driveway speaking to a friend. He ushered me inside and introduced me to his mother, and we sat down at the dining room table.

Just over a year before, on August 1, Rebecca had dropped by out of the blue around lunchtime with Talon in tow. She handed Marilyn a photo album and other mementos of Talon, who Marilyn had helped raise and who shared a bedroom with her other grandson, Ashton, when Talon was there. Rebecca, she said, told her they were leaving town, that they “had to move to be safe.” Safe from what? Marilyn asked. Rebecca wouldn’t explain. And she was vague about their destination: she said that she, Talon, and her younger sister, Christine, would be driving to West Virginia, where her father lived. Marilyn didn’t think Talon had ever met that grandfather. Then, to forestall the possibility that Marilyn would ask Talon about the trip, Rebecca whispered to her not to bring it up, because he doesn’t know—he thinks we’re just going camping.

Another relative was told a different story. Christine said to their stepsister, Trevala Jara, that they would be heading into the wilderness to live off the grid. Trevala, who saw Christine every week, knew that Rebecca had spent much of the pandemic glued to her computer, growing increasingly obsessed with conspiracy theories and the end of the world. She feared vaccines, technology, and the power of global elites, and thought that the only escape was to get as far away from other people as she could.

“At first, Christine told me she wasn’t going with Becky,” Trevala recalled. “She thought it was crazy to do it, mainly because they didn’t have the experience.” But then one day, in late July 2022, Christine told Trevala that she had changed her mind, that she would accompany her sister and Talon to support them.

Trevala offered what she thought was a better solution. “I said, Don’t go to the woods—go to our place in South Park. It’s got an RV and a generator.” Trevala and her husband, Tommy, had an off-grid property in Park County, west of Colorado Springs. But Christine said that Rebecca wouldn’t budge—she wanted something more remote. Christine handed Trevala the urn containing their mother’s ashes, and also asked her to help find someone to take care of her cat, Oreo. Christine even urged Trevala to take her old car but couldn’t find the title for it.

Talon was by all accounts a happy boy, warm and easy to be around. “Every time he was over here, he’d pass me and say, ‘I love you, Grandma,’” Marilyn said. And he was eager to please. His father, Eric, told me that no sooner would Talon do something wrong than he’d turn himself in; his conscience was almost too strong. Talon got on well with Eric’s two eldest children, Emma and Ashton. But according to Marilyn, “He wasn’t well socialized. He had friends in elementary school. But when COVID hit he was just finishing fifth grade.” Rebecca pulled him out for reasons that were unclear to her family. She put him in the school district’s online program for the next two years. Rebecca decided he should stay in online school even after the pandemic died down, according to the Burdens. Her resolve to keep Talon home, Eric said, extended even to questioning why online students had to pick up their new laptops in person.

In place of friends, Talon had his iPad. Rebecca forbade him from using social media, so like many kids his age Talon played games. In addition to Super Mario Bros., his favorite, he enjoyed Minecraft and was deeply immersed in Roblox, the online ecosystem that approximately half of American kids under 16 have visited. Going to school digitally had shrunk his flesh-and-blood social world, and his online connections became more important. As the date of his departure approached, he started telling his Roblox friends, without explanation, that he would soon be leaving. Apparently, despite what his mother would whisper to Marilyn, he did know about the plan to move permanently off-grid, and he knew that it was a secret.