Where There’s a Way, There’s a Will?

Pictured above is a tractor — a Model C made by a company called Case, originally from 1934. Like many tractors, it was used by farmers to till the land — they’d take the machine out in the field and drive it around, digging up the land and overturning it. This prepared the land for seeding, ultimately allowing farmers to grow whatever crop they need to feed their families and sell at market. Tractors are a vital, useful tool for anyone looking to turn a plot of land into something valuable.

And it can also help protect your family in another way — as the farmer’s last will and testament.

When it comes to wills — and inheritances generally — it’s hard to generalize about the law. Each jurisdiction has its own rules; in the United States and Canada, what’s true in one state or province may not be in a neighboring one. But as a general rule, you’re better off having a will than not having one. Dying without a will is called “intestacy” (you’ve probably heard of people who “died intestate”) and in most places, if you’re in that situation when you pass on, your estate usually needs to go into probate — which means the courts have to deal with it — before your next of kin receives your assets. Sometimes, that’s not terribly difficult or lengthy of a process, but it’s still best avoided when possible. Not only is it inconvenient for your grieving family, but you never know who will come out of the woodwork to try to get a share of your estate.

When Cecil George Harris went out to his farm in rural Saskatchewan on June 8, 1948, he probably wasn’t thinking about such legal issues. As CBC News recounted, “the plan was to take his Model C Case tractor to a quarter section a few kilometers north of the home farm to work on the field with a one-way plow.” But his day, sadly, did not go as planned. We’re not sure exactly what happened (for reasons that are about to become clear, and that you’ve probably already correctly guessed), but most likely, the tractor stopped working. Harris went to repair it — something he had done many times before — but tragedy struck. Per CBC News, “the tractor engaged and rolled backwards. Harris was immediately rolled under, pinned by the tractor’s huge left rear wheel, sitting upright between the one-way and the tractor.”

Harris was pinned for hours. Rescuers eventually were able to pull him from the machine, but it was too late; he made it to the hospital but died a few hours later.

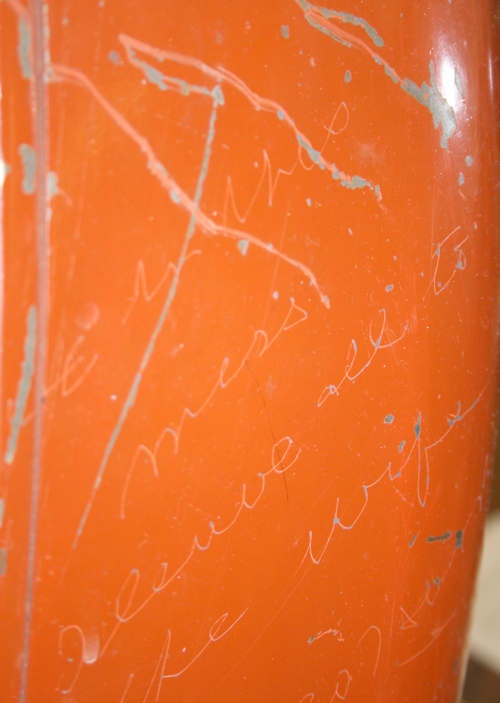

The next day, according to Global News Canada, some of Harris’ neighbors came to the site of the accident, perhaps to help figure out what happened. And they found that Harris had left his wife a gift of sorts, as seen below.

That’s a panel from the tractor, and on it are etched a few words. It reads “In case I die in this mess, I leave all to the wife. Cecil Geo Harris.”

The etchings in the tractor part were what’s called a “holographic will,” or a will written by hand by the testator. It lacks the formality expected of typical wills and therefore, there was a lot of question whether the courts would accept this one as Harris’ true intent. But his wife tried to use it anyway — and succeeded. As CBC explains, the tractor part “was preserved, used as evidence in court, and within weeks of Harris’ death, his estate passed uncontested to his wife, as per his clear wishes.”

Today, the case of Harris’ will is often taught in law schools as an example of testator intent — and the tractor part, therefore, is seen as an important artifact in legal history. It currently resides, on display, at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Law.

Bonus fact: In 1798, an English commoner named William Jennens died, leaving behind a fortune believed to be in the realm of £2 million (about £211 million in today’s value, or more than $270 million US). When he died, he had a will in his coat pocket, according to the press reports at the time (per Wikipedia’s editors), but he hadn’t signed it. As a result, his estate was the subject of many, many lawsuits — and ultimately, paid out very little. It took more than a century for the claims to all be resolved, and when they were in 1915, legal fees had eaten away at the entire would-be inheritance.

From the Archives: The Tractors that Turn Farmers into Hackers: Somehow, this is still an ongoing dispute.